Culture & Community | Arts & Culture

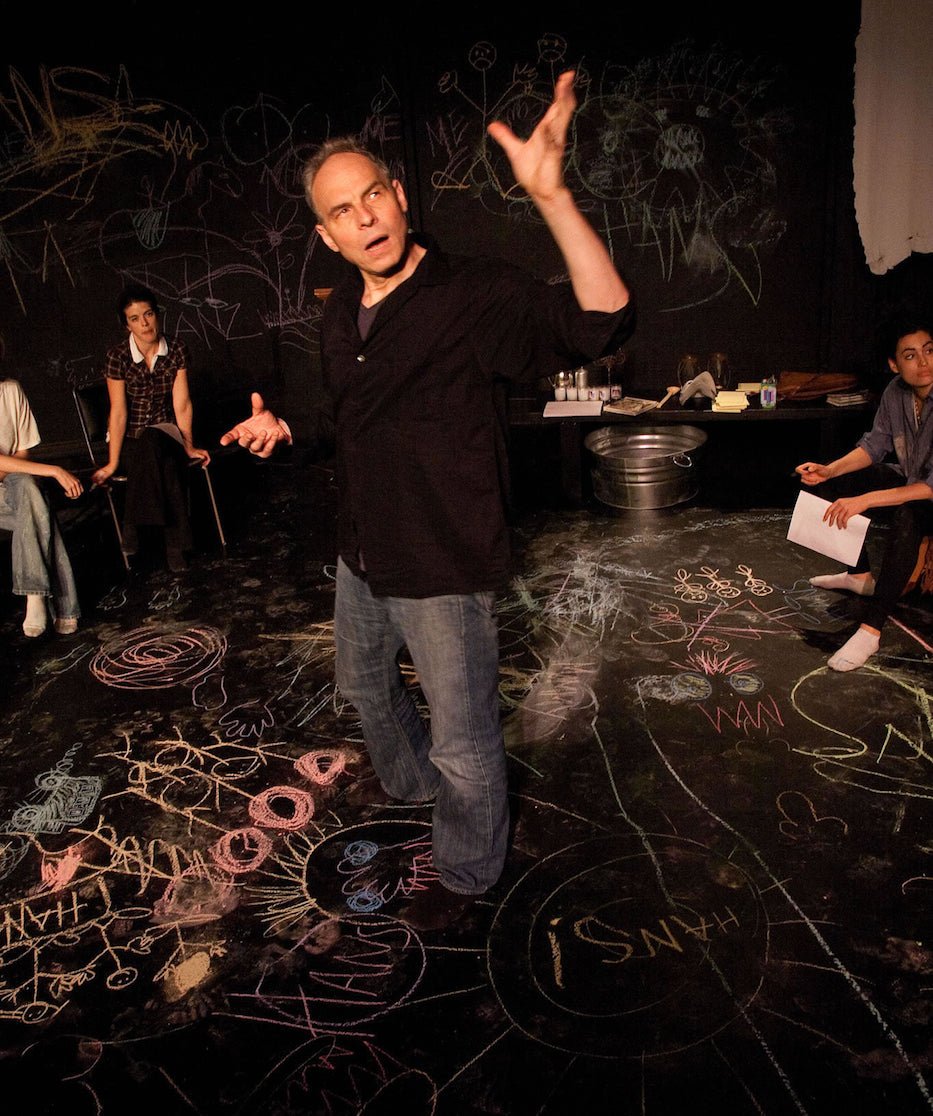

Pilot on the set of Hans: A Case Study in 2011. Contributed Photo.

It’s not hard to imagine David Pilot’s life in film. The camera opens on a shot of 863 Orange St., where a tree pit waits for a new sapling. It pans to Worthington Hooker School, where a pint-sized David is trying to get the whole classroom in on a joke. It jumps to Hamden Hall, where he and a friend are stealing a lawn sign from the campus in the dead of night.

The camera never stops. The lens sweeps to Vassar College and a rent-controlled apartment in New York City, where a couch waits for its next visitor and it feels like the score from RENT might start at any minute. Pilot’s baby face explodes into a smile over a small girl in a stroller. It zips down the sidewalks, finding its way back to New Haven every time. At the end, the camera just keeps rolling on a stretch of State Street, where the buildings fit snugly into each other under a low-hanging blue sky.

Friends and family are remembering Pilot’s life in those sun-soaked vignettes this month, after he died unexpectedly at his Pleasant Street home on March 7. He was living in New Haven’s East Rock neighborhood, less than a mile from where he grew up. In nearly seven decades, he left his creative footprint across the city and beyond, from filmmaking at the city’s Long Wharf to playwriting and film screenings at the library. He was 67 years old.

Some of Pilot's signed work. Lucy Gellman Photo.

In over a dozen interviews, longtime friends, artistic associates, quirky bibliophiles and film aficionados painted a portrait of a painter, photographer, filmmaker, poet and playwright who loved hard, checked in on his friends constantly, and was in creative motion for over six decades. His daughter, Jessica Pilot, and longtime girlfriend Jules Gedalecia are now planning a memorial and exhibition of his work for late May. His postcards, which capture New Haven in snapshots, still peek out from racks at Elm City Market, Atticus, and Nica’s.

“He was just really thoughtful, and his job was really the people in his life,” Gedalecia said. “He was constantly talking about ‘this person, or that person,’ and a lot of these people I’ve never met … but I feel like I know them really well. I just don’t know anyone that has that many lifelong friends. He didn’t lose people. He was just so generous.”

“David was just one of these old school New Haven characters who kind of embodied a segment of New Haven that is becoming lost or is disappearing,” said Aaron Goode, who often saw Pilot filming at Never Ending Books. “A vanishing slice of New Haven life.”

The Making Of David Pilot

Pilot at City Wide Open Studios in 2019. Contributed Photo.

Pilot grew up in a house on Orange Street, the eldest son of Gloria Valentine and Martin Pilot. From the beginning, Valentine was largely a single mom: she raised Pilot and his little brother Josh without much assistance, friends said over multiple interviews. At home and at work, she played the piano, danced avidly, and acted. Before children, she had been a flight attendant, and then an actress. She had been part of a touring company for the Seven Year Itch when she found out that she was pregnant with David. Martin, who lived nearby, was a psychotherapist who later featured in several of Pilot’s scripts.

“She was an amazing character, an unbelievable character” who was also hard on her two young sons, recalled James Frost, a longtime friend of David’s brother Josh who became close with David in adulthood. During the day, Valentine worked as a dance and yoga instructor at Yale University and the New Haven Lawn Club, exposing her kids to the practice long before it became a multibillion dollar industry. It remained part of Pilot’s life, and a favorite activity to teach his friends, until his death.

From Valentine, Pilot inherited a wit that stayed with him in and outside of the classroom, and later behind the lens of a camera. As a kid, he attended Worthington Hooker School, then Hamden Hall. He fell in love with the city around him, completely at home in its parks, pizza parlors, old-school record stores and book shops that no longer exist. When he was in eighth grade, he bought a Vivitar Super 8 movie camera and “just started shooting around New Haven,” he recalled in a 2016 episode of “Deep Focus” on WNHH Community Radio.

Richard Peck, who met Pilot in the fourth grade, remembered him as immediately charming, magnetic and often mischievous. Together, the two explored the city, from a Long Wharf Theatre still in its infancy to plays at the Yale Rep. In 1970, the two had a chance to act with Henry Winkler and Jill Eikenberry in “The Physicists,” a student project at what is now the David Geffen School of Drama.

As a young artist, Pilot cultivated both a sharp eye and a rule breaking streak that would serve him for decades. In 1970, he cut class at Hamden Hall and brought a film camera to the May Day rally on the New Haven Green, winding through the crowd. In 1971, he went to the May Day protests in Washington, in footage that he showed at the New Haven Museum in 2015. Before graduating, he and Peck also stole Hamden Hall’s sign (the word he used was “borrowed” in an interview about the incident) for three decades. A copy of the school’s alumni magazine later featured him posing with it long after he’d fessed up to the crime.

“He always sort of pushed me to do things that I felt uncomfortable doing,” said Peck, now an economist living outside Chicago. When the two went to college—Peck to Oberlin and Pilot to Vassar—they remained extremely close. After high school, the two rode their bikes from New Haven to Montreal, ostensibly egged on by a server at Modern Pizza who insisted that they couldn’t do it. After their sophomore year of college, they rode their bikes across the West Coast, hitchhiking from Seattle to Los Angeles. After graduating they headed to Europe, where Pilot “insisted” that the two rent motorcycles.

It was part of a wild ride that their friendship would take for the next four decades.

“Saving Manhattan” And The New York Years

Pilot never outgrew the doe-eyed, boyish face he had as a kid, and as he got older, it became part of his charm. When he left New Haven in 1971 to go to college, it was never a final goodbye to the city he loved so much.

At Vassar, “there was this transformation that sort of occurred over time,” Peck said in a recent phone conversation. Pilot honed his skills in photography and film, and also nurtured his love for literature and language (he never stopped writing, Gedalecia said—his Pleasant Street home is filled with at least five old laptops, over a dozen hard drives, and boxes of paper, poetry, well-loved annotated books and scripts that prove it). When he graduated in the mid-70s, he moved to New York City to continue his creative work.

New York, then in the midst of its own transformation, birthed some of Pilot’s most explosively creative years. In the 1980s the city gave him his daughter Jessica, who last saw him in New Haven last summer. Now a producer based in Brooklyn, she remembered him as “my cool guide to life,” when life meant growing up “fast and slow” in a city unlike any other place to raise children in the world (“While the city has everything, it lacks everything,” she mused in a recent phone call).

While Jessica lived primarily with her mom—Pilot and his ex-wife divorced when she was seven—he was her point of entry into Jivamukti and OM yoga, spiritual mysticism, experimental and fringe theater and later house parties that he would DJ from his East Village apartment. In a phone call in mid-March, she called him as “a true bohemian,” whose conviction in trusting one’s gut set her on her own path to comedy, radio and television production.

“He just marched to his own drum,” she said. “He was very much an independent thinker and an independent filmmaker and artist, and he very much believed in the arts.”

A still from Saving Manhattan.

Meanwhile, Pilot’s creative work also flourished. He appeared at fringe festivals and playwriting workshops and churches that doubled as after-hours theaters. He turned his couch into an extra bed, where Frost took up temporary residence before moving on to Philadelphia. From a rent-controlled apartment in the city’s East Village, he and the actor Michael McCartney began work on Saving Manhattan, a dark comedy about a street preacher (Carl) and the city to which he delivered his gospel. McCartney had just graduated from Skidmore College, and Pilot became his mentor.

Over four months of filming in 1996, the two looped in Valentine, a young Amy Poehler, the founders of Jivamukti, and half a dozen actors who are now recognized names in the industry. McCartney, who played Carl, remembered it as “one big long story of insanity,” in which he and Pilot would walk through the city with a video camera, holding McCartney with his left arm as he filmed with his right. On more than one occasion, McCartney would walk into Times Square—or sometimes it was a born-again Manhattan church, or a crowded street corner, or a yoga lesson—and begin preaching.

“He was a magnificent dreamer,” he said of Pilot. He recalled a day of filming, during which he and Pilot stationed themselves close to a chapter of the Sons Of Light, a group of Black activists named after John Williams’ 1969 novel Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light. McCartney started arguing with them about the existence of God. Pilot held on to his friend’s arm—and caught the whole thing on tape. By the time they had moved from filming to editing, they had over 40 hours of film to sift through.

Years later, Saving Manhattan became Pilot’s great white whale—he never finished it, although a 32-minute cut exists on Vimeo. In the glimpse that viewers get, Pilot follows McCartney as he preaches across the city, frequently coming to barbs with its residents and business owners. Jessica Pilot, who now lives in Brooklyn, confirmed that she and McCartney will be finishing it together posthumously in Los Angeles over the next several months.

Photographer and filmmaker Jo Blanco, who met the two during those years, remembered Pilot as instantly, effusively welcoming, with a talent for film and street photography that inspired him. After moving to New York City in the 1990s, he shared an editing suite with Pilot, where the two spent hours and hours working on their individual projects and chatting with each other to fill the quiet in between.

The West End Theatre during Hans. Contributed Photo.

When Pilot wasn’t there, he was finishing and producing dozens of scripts, including texts based on the American Slave Code and Malicious Maleficarum. In 2007, he began to work on Skin In The Game, a documentary on Midwestern internet porn sensation Raven Riley that would later premiere at the New Haven Documentary Film Festival. In the early 2000s, he also wrote and directed Hans: A Case Study, loosely based on Sigmund Freud’s 1909 case study of the same name. In Freud’s 1909 study, Hans is a five-year-old child with a fear of horses—the erogenous root of which Freud was perhaps more interested in than the fear itself. The study later became an enduring part of how Freud wrote, spoke about and understood castration anxiety.

Pilot reimagined the work with a cast of rotating Freuds (actor and playwright Austin Pendleton, psychotherapist John Munder-Ross, poet and performance artist Valery Oisteanu, and perhaps most famously André De Shields), original music from a young David Cieri and the Complex Electra Orchestra, and an entirely female ensemble in the roles of mother, father, Hans himself, and a number of ancillary characters. He wasn’t shy about the work’s autobiographical slant: notes on the work from 2011 identify Pilot as the subject of a case study himself.

“Working on the play has been as much of a catharsis as it has been an exploration and understanding of Pilot’s own personal relationships with his family,” read a program note from the performance.

In September 2011, the work made its debut at the West End Theatre, which lives in the Church of St. Paul & St. Andrew at West 86th St. in Manhattan. A talkback that brought together artists and psychoanalysts followed each performance.

The tech director at the West End Theatre at the time, Sean Ryan called Pilot “a mentor to me,” whose expansive imagination made wild, audacious dramatic scenarios entirely possible. By 2011 Ryan knew Pilot through his sister Meg, who had worked as a producer for him in the 1990s. The performance, and a summer of rehearsals that preceded it, was the first time “we sort of found our groove,” he said.

The cast—its layers of psychological subtext notwithstanding—became a family. “There were like, marriages and babies from this one summer,” Ryan said. The two collaborated on a subsequent project, based on Carl Jung’s The Red Book: Liber Novus, but it never came to fruition.

Pilot never lost touch with those friends. Blanco, who left New York for Miami Beach in 2004, called him a “truly truly special” friend who invested in the people he was close to. Decades after he left New York, Blanco estimated that the two still spoke two or three times a week. Pilot could talk about anything, from dogs to his latest screenplay or filmmaking project to the television shows he was watching. The last time he’d spoken to Pilot was the Friday before he died.

“I have a lot of friends and family,” he said. “I don’t have anybody that I would speak to as frequently as I did with David.”

“A Wonderful, Creative Presence”

Pilot's photography. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Pilot moved back to New Haven around 2013, after spending the summer at Frost’s place in Guilford. After packing up in New York, he moved to an upstairs apartment on Eld Street, close to where he was born and closer still to where he spent the last years of his life. After just weeks back in his creative birthplace, he could wax poetic on the Mill River, point out neon and technicolor signs that dated back decades, churn out a new script, and throw down to defend the honor of Modern and Sally’s Apizza. He often did all or many of those in a day.

He threaded himself through New Haven’s vibrant, polyphonic fabric, bridging worlds that ranged from quirky writers, filmmakers, and poets at the New Haven Free Public Library to members of the secretive Society of Santa Maria Maddalena in Wooster Square to City Wide Open Studios’ Erector Square weekend. Frost, who now lives in Chicago but spoke to him “probably every day, almost obsessively,” remembered the sheer appetite with which Pilot took on the city, leaving no stone unturned.

When he visited Pilot after his return to New Haven, it seemed that his friend knew everyone, from the late Arts Czar Andy Wolf to writerly wallflowers he could bring right out of their shells. Many friends jokingly referred to him as the unofficial mayor of the city.

It became common to see Pilot on his bike, criss-crossing city neighborhoods with a big smile and gentle, swooping voice that carried halfway down a city block. For Elm Citizens associated with Santa Maria Maddalena, he was the friendly yoga teacher who popped up in a second-floor classroom on Lawrence Street, ready to instruct old-school Italians to ease into down dog and happy baby. For friends at the library, he was a willing and open ear, always ready to deliver criticism with a gentle smile. For others he was the careful eyes behind photographs at the old Lulu’s, where East Rock Coffee now stands at Orange and Cottage Streets.

William “Boomer” Harold, a piano curator at the Yale School of Music, remembered meeting Pilot in 2013, shortly after he’d moved back to New Haven. After an introduction from Frost, Pilot invited him over for a Modern pie. When Harold walked in, “David just came across the room with his arms outstretched,” he said. The image remained in his mind for years, as the two grew close roasting oysters in Harold’s backyard, attending shows at Long Wharf Theatre, and comparing notes on the most recent season of Ozark.

Those years, like the three decades in New York that had preceded them, remained some of the most fruitful in Pilot’s career. Within a year of returning to New Haven, Pilot collaborated with writer Steve Bellwood on a work titled The Specials, presented at the Whitney Arts Center and the old Luck & Levity Brew Shop on Court Street. He began teaching yoga—almost always informally—to any friends who would take it. He became a fixture at the NHFPL’s Elm City Writers Group and Never Ending Books, where former owner Roger Uihlein remembered him as “wonderful, creative presence.”

He also launched the Making Of the Making Of (MoMo), a creative initiative that was entirely interested in process, rather than product. Initially, the series operated out of the old Lovell School, where landlords Bob and Susan Frew gave him space for several months. In one meeting early in MoMo’s existence, Bob “Bobcat” Carruthers remembered watching actor Terrence Riggins perform in the basement, and “being just blown away by it.” The two remained close until Pilot’s passing.

Every friend interviewed for this article had a different story of that creative footprint. In 2016, librarians Bill Armstrong and Seth Godfrey—the latter of whom overlapped with Pilot at Hamden Hall—celebrated “David Pilot Day” at the library, with an afternoon of Pilot’s screenings and artist talkbacks. Just down Elm Street from the library, Pilot graced the closet-sized offices at WNHH Community Radio more than once, where he joined host Sharon Benzoni to talk about the 2016 premiere of Skin In The Game and Thomas Breen to marvel at home movies.

Six years ago, he looped librarian William Armstrong and Carruthers in on a miniseries tentatively titled Buber Driver, based on the work of philosopher Martin Buber. The premise, for which Pilot mapped out a 20-episode arc, was simple: a Buber-like taxi driver would set a flat fare, and talk to riders as he ferried them around New Haven. In particular, Pilot was interested in "Buber's philosophy of meeting," Armstrong said—that when "people truly meet, between that meeting, you find the divine."

"He was just very open and very warm," Armstrong said, adding that Pilot developed a recent, spiritual and philosophical interest in the Upanishads near the end of his life. "I kind of think he saw life as a play and wanted everyone to be in this production that we are all part of, and for all of us to be warm and loving towards each other. And to share the stage together—to be conscious of each person, so that they can shine in their role."

Years later, Frost’s observation that “you could tell that he never just had a trivial conversation” rang true: it wasn’t uncommon to run into Pilot in the produce aisle at Nica’s, and catch up on a year of life as he carefully lifted tongfuls of spinach into a plastic bag.

It was that interest in people that led him back to Gedalecia, a dancer-turned-physician assistant who met (or re-met, as she tells it) Pilot when he was a patient at Yale New Haven Hospital in March 2019, recovering from carbon monoxide poisoning. The two had met 25 years earlier, through Skidmore professor Debra Fernandez. Then three years ago, the same professor called her with the news that he was in the hospital.

In true Pilot fashion, “he jumped out of his bed and gave me this huge hug,” she said. As Gedalecia studied for her board exams, Pilot became her guide to New Haven. She was struck by his curiosity, from nightly phone calls to small tokens of affection that he always brought with him when he visited. Their friendship bloomed into a relationship from there.

Together, the two took on the city, one snapshot and slice of pizza at a time. Pilot often joked that he wanted his ashes to be scattered in the Mill River, sprinkled in front of Modern, and liberally tossed from the top of East Rock.

“He made you feel like you were the only person in the room,” she said. “He gave you his full attention. He was always interested in what anybody had to say. Very engaging. Very gregarious. Very curious. And very open.”

“This Is Your Pilot Speaking”

Now, friends and family are figuring out how to exist in a world without him. Victoria McAvoy, who co-founded Elm City Writers with Armstrong, said she is still reeling from the news. When she first heard about Pilot’s death, she was at the Institute Library—the same place she’d heard him deliver a eulogy for someone who had taken his own life several years ago.

“Pilot and I were significant to each other in a distant sort of way,” she said. “It’s not too corny to say he changed my life. My perspective on life grew broader and sunnier because of this man. And I wonder if I ever stop missing him.”

On the last Friday of March, Gedalecia began sharing dispatches from Pilot’s apartment, which she has been cleaning out with assistance from Armstrong, Jessica Pilot, and a rotating door of friends. In the first of the images, titled “This Is Your Pilot Speaking,” Pilot’s ballpoint scrawl stretches across a page, set on a backdrop of bright wallpaper. Literature, films, plays, art, are guided dreams fulfilled, it reads.

Another is a single page of yellow memo paper, with a sketched out episode for something called “The Fighting Brothers.” Another is a voice memo of Pilot singing to himself on the night that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died.

Other New Haven mementos—a discarded, char-kissed pizza peel from Sally’s that still stands against one wall, beside stacks of books—have yet to make the collection. On social media, Gedalecia also wrote a post chronicling Pilot’s last day in New Haven, most of which he spent with her. The two ate Modern Pizza and homemade chocolate cake, drank Foxon Park soda, and watched good-bad television.

“He just thought New Haven was the best,” she said. After the two said goodbye, he rode the short distance home on his bike, texted 10 people and had four hour-long phone conversations with friends from all across the country. He was in constant contact with his friends until the very end of his life.

“He used to say to me, ‘Love means having to be sad sometimes,’” she concluded. “And now I get to say something he always loved to hear: ‘You're right.’"

His legacy will live on on Orange Street, she added. After Pilot’s death, Harold reached out to the Urban Resources Initiative (URI) asking if the group could plant a tree in front of Pilot’s childhood home at 863 Orange St. It turned out, URI found in its records, that someone had already requested the same spot.

It was Pilot, who had seen the city cut down his childhood tree, and made the request in September of last year. He had simply never gotten back to the organization with the type of tree. Now, his loved ones are finishing the job for him.

“That just felt really great,” Gedalecia said. “It was like, ‘Okay, I know that’s what he wanted.’”