| Lucy Gellman Photos, with permission of the artists. |

At first, you’re not sure if she’s looking at you or beyond you. Her feet are planted squarely on a patch of grass that’s been pressed flat, trampled by so many feet that have come before hers. Brown fatigues cover her neck to her ankles, face and head wrapped in a balaklava. Only her eyes peer out. A rifle hangs casually from her right hand. Around her, a tent city smudges and blurs at the edges.

A member of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, or ELZN), the woman is one of tens pictured in Mujeres que Luchan, a new exhibition by artist-activists Vanesa Suarez and Constanza Segovia at 266 Grand Ave., tucked away behind an insurance office on the first floor of the building. After opening with a crowded, buzzing reception last weekend, the show runs through mid-December. Segovia said the two hope to have a lecture and closing reception before then, and use the space more often going forward.

Mujeres que Luchan is supported by Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA) and Hartford Deportation Defense (Defensa contra las Deportaciones), in which Suarez and Segovia are both active members. But the exhibition has its roots in Chiapas, Mexico, where the two traveled in March to celebrate Día Internacional de la Mujer, or International Women’s Day, with thousands of women from around the globe and the Zapatistas who call it home. The invitation came from the ELZN, who Suarez said opened both their land and caracoles, or municipal groups, for the first time in decades.

Located in the mountains, Chiapas first became a stronghold of the ELZN in 1994, when a group of Zapatistas rose up to protest the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), taking nearbySan Cristóbal de las Casas and the surrounding area by force. Since, they have controlled the area espousing a mix of matrilineal society and Neozapatismo, where land sovereignty and indigenous rights go hand-in-hand with anti-capitalist theory and matriarchy.

As an activist and an artist, Suarez said she saw the gathering as both an exciting opportunity for herself, and a great responsibility to her community. When ULA discussed the invitation in its weekly meetings—open to women only—several New Haveners wanted to attend but couldn’t risk traveling, due to their undocumented immigration status. Suarez soon realized that the things she had thought of as barriers—airfare, logistics, travel fees and vacation days that her job didn’t want to give her—were small compared to state-sanctioned borders.

“What does that mean, when there are fronteras, when there are borders?” she asked aloud at the show’s opening. In part, she added of the women who could not attend, “I went for them.”

| Vanesa Suarez with an attendee. "What does it mean, when there are borders?" she asked. |

Once she had gotten settled in Chiapas—she traveled there solo, and then met up with Segovia as the gathering and workshops began–Suarez found that she was both mesmerized and fired up by what she saw. During the day, Suarez sailed from one activity to another, listening to women from around Latin America and the broader globe speak about their own struggles, and what rebellion, social justice, and education looked like to them.

At night, women would sleep in tents that they had brought to Chiapas, or in cabins that fit tens of them at a time, sleeping beside each other like longtime friends and sisters. Then in the morning, attendees would push their belongings to the corners of the cabins, and create a bare space for more presentations to take place. As Suarez documented every moment she could, a certain calm settled over her. She had wanted to believe that a world without borders, without capitalism, and without patriarchy was possible. Suddenly, she was seeing that it was.

“There was this feeling the whole time—I felt so safe,” she recalled. “Being there was part of a healing space for me, from capitalism and patriarchy, I felt free.”

Back inside the Grand Avenue space, those memories now speak, whispering wisdom as viewers approach them. With a few fellow members of ULA, Suarez and Segovia have transformed the large, harshly lit white-and-tile room into a full-fledged art gallery with work suspended from the ceiling and hung just so on the walls.

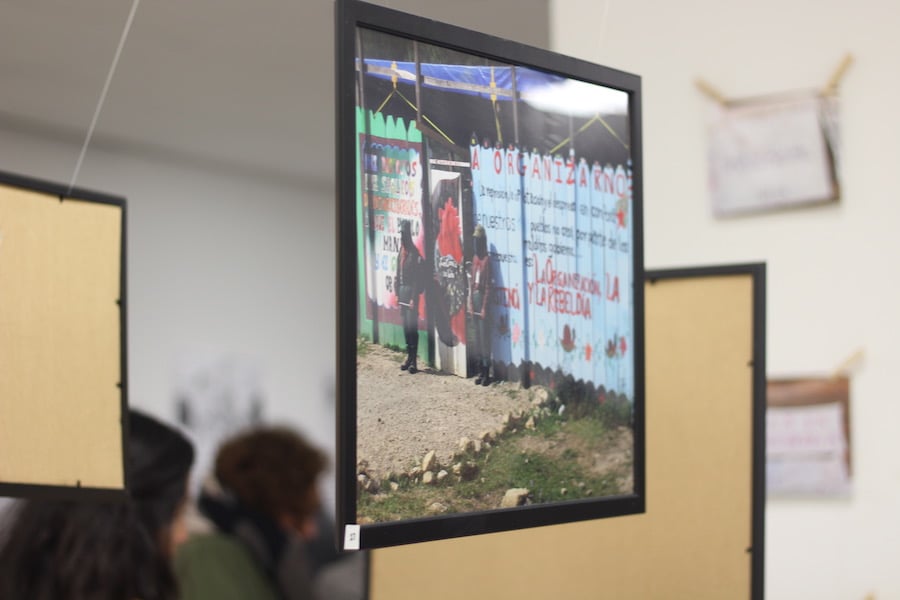

Some of the photographs announce the Zapatista way of life with bright, vivid public artwork, depicting painted cabins and fences alongside rituals for the land. In one, Suarez captures green and blue picket fences with women standing guard outside, words like La Rebelda announcing themselves in thick, curving red letters. Across from them, photos of birth wink out from the walls, women heaving new lives into being, eyes closed and faces turned upward.

Other images are entirely documentary, chronicling the country’s epidemic of feminicidio—the intentional, and often very violent, murder of women known as femicide—in a series of photos held up by clothes pins. One, from the third of July 2017, reads like a horrible poem:

No se sabe mi nombre

Tenia 50 años

fui torturada junto

con un manor que dicen

pudo ser mi higo, tenia

atadas las manas y los

ojos cubiertos con cinto

My name is unknown

I am 50 years old

I was tortured together

with a youth who

could have been my son

they tied my hands and

eyes with a belt

But the majority of Suarez' work brings those two sensibilities together, her trained eye giving way to a constant sense of witness and wonder. Some are full of surprise, like a table covered in fresh fruit that Suarez said never seemed to run out, despite some 14,000 attendees that converged on Chiapas in three days. Others freeze a moment at just the right time, like a still from a workshop where a woman stands speaking to a packed cabin. An image of Cesar Manuel Gonzalez Hernandez, one of the 43 student teachers to disappear from Ayotzinapa, Mexico, stretches across her shirt. Her eyes lock with the camera in a plea for justice.

In one photograph on the far side of the gallery, Suarez has honed in on a cluster of Zapatistas as they watch a dance dedicated to victims of femicide, dancers' white dresses splattered with red as they move across the floor. In the righthand corner, a cluster of Zapatistas watch intently, their faces covered everywhere except the eyes.

“I was just so struck by their eyes,” she said. “They’ve lived this. They’ve lived this kind of violence. They know what it looks like to be born, walking an uphill mountain, every day.”

When Suarez returned to the U.S., she said she initially had trouble readjusting to society. It wasn’t just the constant reminder of state-sanctioned borders, but also how much more space men took up in rooms where she was speaking. Not just one or two times the space, she said, but five times the space, to the point where she and other female colleagues could barely get a word in edgewise.

“Women’s struggle is important,” she said. “When women are free, we will all be free."

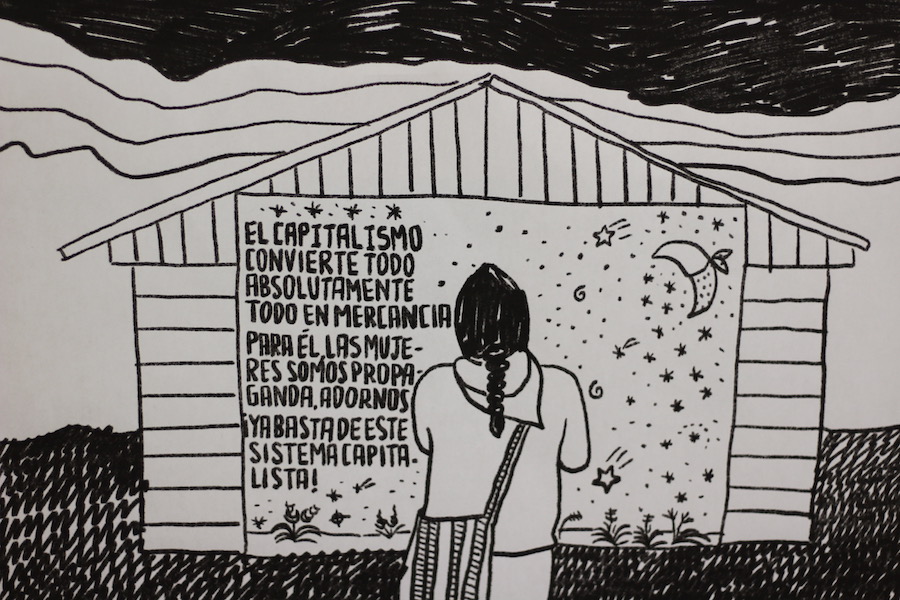

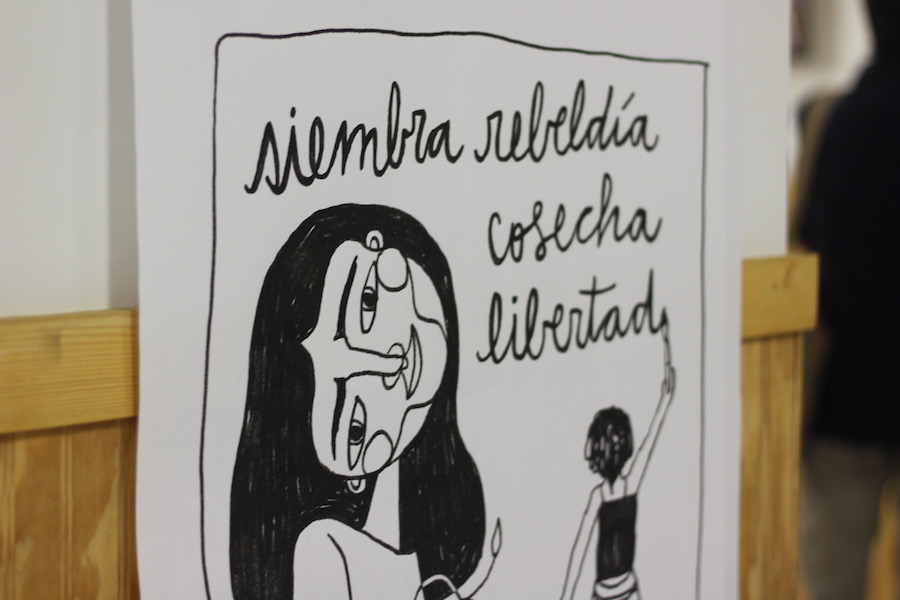

On the other side of the gallery, Segovia’s rich drawings—thick, detailed images with large, angular text beneath them, similar to a graphic novel—expand the story. At the base of the first image, she situates her viewer in the mountain community, a figure reading letters that are scrawled on the side of a cabin with shooting stars and a crescent moon beside them. She is dressed simply: a thick sweatshirt with the hood removed, woven shoulder bag, and pants or a skirt we can’t really make out. A thick braid runs midway down her back.

El Capitalismo/convierte todo/Absolitamente/Todo en Mercancia/Para él las mujeres/somes propaganda, adornos/Y abastadeeste/Sistema capitalisma!, the message reads.

Like Suarez, Segovia felt an instant pull toward the workshops and performances that women had organized, trying to catch as much as she could in the 72 hours that they were there. While she had initially brought art supplies and planned to document more on site during the three days, she ultimately kept that work to smaller-scale sketches and journal entries, and then worked off Suarez’ photographs with the words she’d committed to paper in the moment.

“It was a dream of mine to go see how the caracoles are organized, how the land is used, the different aspects of life there,” she said. “So it was kind of like layers. It was overwhelming in a way, because of all the layers, but also it was so energizing.”

“I just knew that I wanted images and words to come together, and I wanted that kind of like diary, documentation,” she added. “But now I want to do more. There’s so much more.”

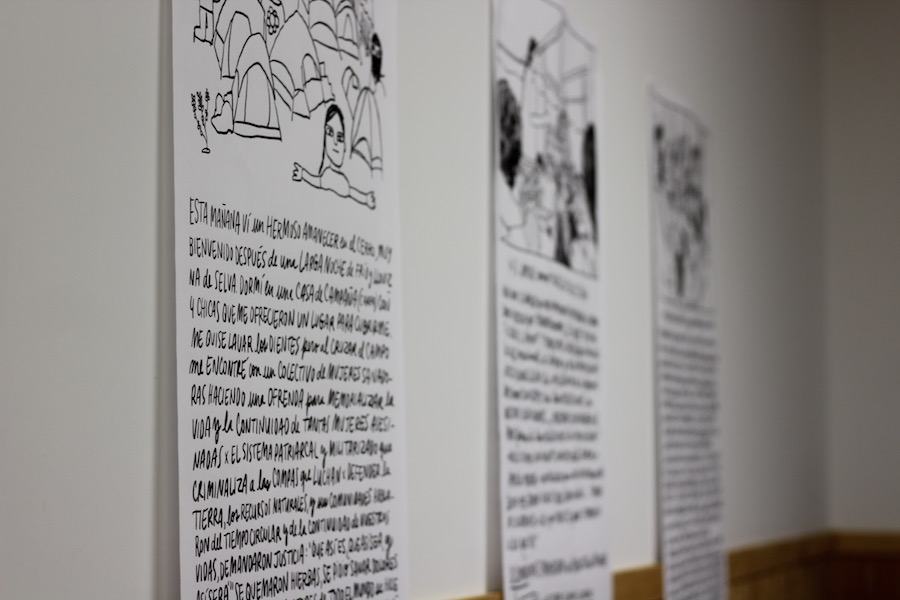

In telling the story of the trip, Segovia has relied on personal anecdote, giving viewers a more intimate look at the experience. In her second of several panels, she recalls her own journey to Chiapas, initially marred by fits and starts with transportation. When she finally got to Chiapas—itself the result of some maneuvering with a rented van—she was exhausted, and unsure of where she would sleep for that first night.

The solution: an uncomfortable spot that two women offered her in their tent, saving her from the cold jungle. When Segovia woke up the next day, she said “it just felt like peace” for the first time in a very long time. The sun hadn’t even come up. But Segovia went outside, and stumbled on an offering that a collective of women were doing in a field, honoring indigenous communities. She later connected with the facilitator, a radical Guatemalan feminist named Lorena Cabnal.

“That feels like a very special moment, because that was like the beginning of it, but also like the coming in to the experience to take it in. Like, without being on this survival mode.”

To watch remarks from opening night, click on the video below.