Reporting from the road | Arts & Culture

| Dey Hernández, Pampi, and Kimberly Barzola. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Boston—McKersin Previlus was letting the music take control. From the front of the room, he walked a few rows back, taking attendees by the hand and pulling them into his orbit. They eased into the dance, watching Previlus for cues. Shoulders softened. Ankles rolled and rotated. Arms extended.

Then the music stopped. As audience members trickled back to their seats, they saw that signs connoting new barriers had taken their spots: overzealous critics, penny-pinching arts funders, and long-standing board members now “occupied” their places. They stood uncomfortably, looking at where their butts had been just minutes before.

“How does it feel to be displaced?” Previlus asked. The room fell into silence.

Saturday, Previlus was one over 30 speakers and presenters at the inaugural Arts Equity Summit, a project of Arts Connect International (ACI) with support from the New England Foundation for the Arts and the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA). Held between the ICA and nearby District Hall, the conference drew over 200 attendees for workshops on representation, equity in arts education, celebration of artists and makers of color, and the role of artists in housing advocacy and divestment.

"Our main intention was to provide a platform and a space for much overdue cross-cultural conversation," said ACI Director Marian Brown, zeroing in on cross-sector analyses of equity that focus on—and celebrate—artists of color.

The conference follows the city’s 2016 creation of a 10-year cultural plan, an initiative that has included hiring city staff specifically dedicated to supporting local artists.

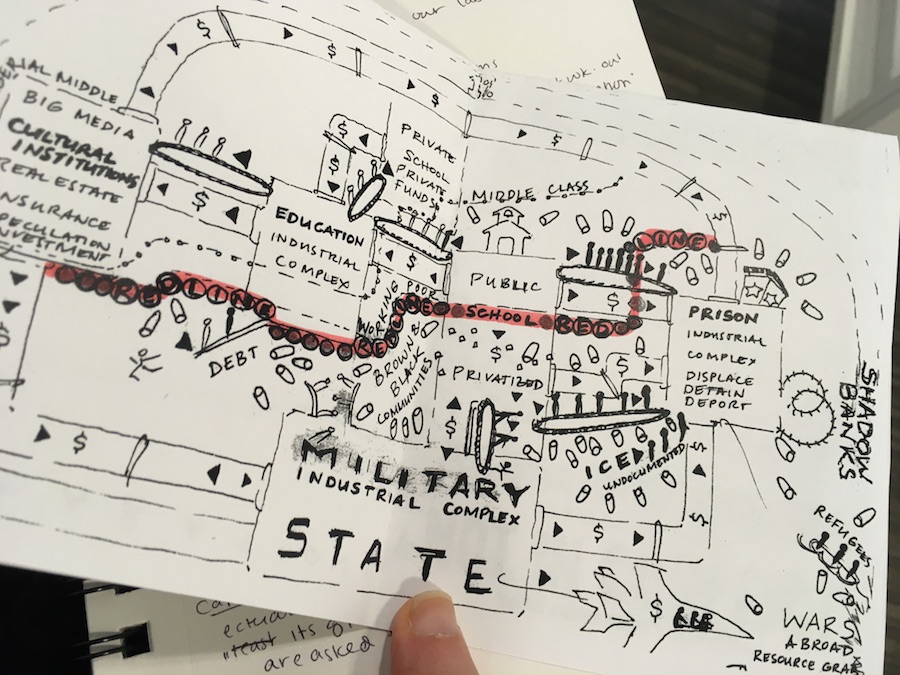

| A homemade booklet from Pampi traced the history of redlining and its connection with both the military industrial complex and less-discussed, privatized "educational industrial complex." |

Saturday, one such workshop seemed as much geared toward New Haven as it was Boston, painting a picture of the city that resonated with the Elm City’s own boom in development and lack of affordable housing. In a panel titled “How Not to Get Chump-Changed: The Artist’s Role in Housing and Divestment Justice,” artist-activists Brandie Blaze, Dey Hernández, Previlus, Pampi, and Kimberly Barzola asked a question that struck close to New Haven’s creative landscape: where do artists fall in the complex network of advocacy work and housing justice?

And can they, knowingly or otherwise, actually be participants in gentrification?

After Previlus’ performance opened the session, Pampi suggested that the answer lies in the forms of capital that artists—and arts supporters—may or may not have. Saturday, those took several forms: social, material, financial, and experiential among others.

“Most of us have social capital,” they said. “Most of us. But do we need it?”

Further, they asked, what happens to those without capital? With a series of homemade booklets, the artist took attendees through a crash course in redlining, through which neighborhoods were deliberately segregated in the 1930s and 1940s under the guise of mortgage lending practices and desirable homes for returning veterans. Almost a century later, its consequences have left an imprint on the city, where the cost of housing has skyrocketed and several once-redlined neighborhoods have become attractive to the same outside forces and developers that have been known to haunt New Haven.

| Pampi: How are artists complicit in gentrification? |

“How are artists complicit in gentrification?” Pampi asked.

A few heads shook around the room. Boston-based artist Ankana told the group she’s watched as landlords give artists space in decrepit, often unlivable buildings in neighborhoods that saw redlining in the twentieth century. Because the artists are there, the neighborhoods become more vibrant. People start moving in; the cost of rent goes up. Artists get booted for slick development, and families are displaced in the process. Several other attendees joined in, noting Boston neighborhoods Jamaica Plain and Dorchester.

But there is also a way for artists to fight it, suggested Ankana. She praised efforts like the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), a collective of neighbors who are organizing together to fight eminent domain and displacement, and using both public art and land sovereignty in their community work. Both she and Pampi encouraged attendees to get to know the groups fighting for housing justice in their own neighborhoods. And to pay artists a fair and equitable wage as a door to access—because their work isn’t free.

“We need to get together and do this work,” Pampi said.

“It’s All About Building Community”

| Brandie Blaze, Dey Hernández and Pampi. |

Several presenters discussed their own life experiences as a launchpad to talk arts, activism and housing divestment. Blaze, a hip-hop artist and poet, recalled learning about the equity gap when she was just eight years old, preparing for a local performance of Black Nativity. Some time before the show, she wandered out into the lobby and overheard two white women chatting.

“They was like ‘you know it’s going to start late, cause it’s gonna start on colored people time,’” she recalled hearing. “And I was like, ‘what does that mean?’”

"It was my first time learning that Black was a negative thing when I was raised to revere being Black," she added.

Years later, that palpable sense of inequity pushed her into activism, planning protests and doing grassroots organizing in the city. She recalled protests where she found herself face-to-face with police, sometimes without support from peers and fellow activists.

But she also found herself burning out, a Black woman trying to navigate through feminist spaces that were often overwhelmingly white and activist spaces that were overwhelmingly male. She began to turn to music as her mouthpiece, practicing a quieter form of activism that was sustainable for her. A self-proclaimed "trap feminist," she said she has stuck to the form because it feels true to who she is as both an artist and an agent of change.

“You have to learn how to navigate through different spaces depending on what your identity is,” she said. “As a Black person, you learn how to navigate through white spaces. As a woman, and especially as a hip-hop artist, you learn how to navigate male spaces.”

She added that artists can achieve wage equity—and divest from poor housing practices—by working collectively instead of individually. She urged attendees to recognize the intersection of relative privilege at which they stand, and use it to advocate for everyone around them.

“It’s all about building community,” she said. “If we’re all working in this together and we’re all using the privileges that we do have—I’m a cis woman, I’m a light-skinned Black woman, I’m straight passing—and use our specific privileges for good, then I think we can start breaking down those walls.”

“We Just Always Show Up”

Previlus jumped in with a different experience. Growing up in Haiti, he was surrounded by people who looked like him. The only white people he saw were representatives of the United Nations, who didn’t stray too far from their bases. To him, they were the outsiders.

Previlus jumped in with a different experience. Growing up in Haiti, he was surrounded by people who looked like him. The only white people he saw were representatives of the United Nations, who didn’t stray too far from their bases. To him, they were the outsiders.

“It’s a privilege, to be honest, to grow up among fellow Black folk,” he said. “We have a culture. We have values, Haitian values. Education is very important. I was doing multiplication by first grade. It’s like very strong culture that has been built up over the years.”

But then he moved to the Boston area when he was eight, and “I started realizing how weird things were around here.”

Attending school in nearby Everett, Mass., he noticed that his white classmates talked to him differently. So did the majority-white educators who helmed his classrooms. Despite the city’s seeming diversity, he could feel a palpable difference between his white and Black classmates, one that arose each time they compared what they’d eaten for dinner or what furnishings they had in their homes.

“Things were weird,” he said. “I’d go to someone’s house and they’d serve me on plates. They’d get stuff delivered. So that’s when I was like, ‘yo, this ain’t fair’ … I started to see how family structures are completely different. And that’s when I realized, this ain’t fair and it’s nothing we did.”

For a time, Previlus was angry at the equity gap, but didn’t know how to address it. Then in college, he met a professor who saw him dancing in an extracurricular club, and asked him to join a project she was doing based around social justice.

“I didn’t see the connection,” he said. “I was like, ‘how does dance have to do with injustice?’ I didn’t get that.”

At the time, the professor struck him as crazy. She was a white woman who showed up at every protest in the city, jumped over police barricades and came to class with bruises on her legs. She explained that she showed up because she was white, and could use her privilege to disrupt the protests without fearing for her life.

“She taught me … how to use what you have, your talents,” he said. “Since then, it’s just been that.”

Now, he continued, he sees artists achieving true equity through an old-school hip-hop philosophy—creative unity. He motioned to Aysha Upchurch, a lecturer at Harvard’s graduate school of education and director of HipHopEx, as he described original hip-hop parties that began with friends and families handing out index cards to DIY concerts, advertising 50-cent admission to parties that doubled as school fundraisers. He praised a culture of community cyphers, where one artist would watch another perform, then go home and practice the routine.

“They learned this stuff by having to survive,” he said. “I feel like that philosophy is what can help artists today. We support one another. We have conversation. We just always show up. We share amongst each other. And then from there, we’ll be unstoppable.”

He added that housing inequity factors into that approach. In Boston, he said, artists and particularly artists of color struggle to find space, even when they may have the financial capital to pay for it.

“You can have money in Massachusetts, in Boston, and you still can’t get space,” he said. “And that space is right there. And there are gatekeepers who are making sure that you can’t get into that space … not having a space makes it impossible for us to do that.”

“We Need Solidarity”

Born and raised by a single mother in Puerto Rico, Hernández cut right to the role of arts in activism and organizing, a practice that has become part of her life as a member of AgitArte, Inc.. Since the early 2000s, AgitArte has grown as a collective of 50 artivists working between Puerto Rico and the Boston area. In 2008, Hernández came to the group through workshop of Papel Machete, a worker’s street collective that pushes for social justice and decolonization through public art and performance. With a background in architecture, she started feeling her way through puppetry and huge papier-mâché figures that she could take into the streets.

“We didn’t even know how to do this stuff,” she recalled. “Most of us were activists and we were doing this work … like, we’re always reacting to something. We wanted to do it differently, and we wanted to engage in a different way. So we bring that work into the streets, into whatever place we can to agitate, and to bring that particular message.”

Hernández pulled up a slide from La Operación, Episodios del Genocidio Boricua (The Operation: Episodes of Puerto Rican Genocide). In it, a masked doctor dips one hand into apapier-mâché woman, her stomach lifting clear off to reveal bright red organs. The performance, held in 2012, was intended to teach audiences about the experiments that American doctors performed on Puerto Rican women during the twentieth century.

She flipped to another slide showing artwork that has come out of Hurricane Maria’s devastating aftermath. In one image, a group crouches before a revitalized moral on the island. In another, a swirl of words fans out from a cyclone shape shaded in green and black.

“The whole world was able to see that in a country that people were literally not having water, the real basics, food … the U.S. was holding the aid,” she said. “So we were responding to that.”

The work has extended to Boston, where artists worked on a public installation last year documenting the death and devastation that still reign in parts of the island. Those kinds of activities that bridge public art and social justice, she said, are part of how artists can work toward equity.

She praised City Life/Vida Urbana, a tenants’ rights organization that has been organizing in Boston for over four decades. For artists to make livable wages, she suggested, they must organize with other members of the working class.

“We need solidarity,” she said. “We need to have in our hands the access and the tools to actually create some sort of sustainable communal living for ourselves … we need to get together and do this work.”