Culture & Community | Design | Economic Development | Misha Semenov | Parklet | Trees

"When you suddenly realize the trees have names and they have characters the way that you walk around New Haven is very different. You’re like: “Oh, that’s an elm tree!” “That’s a sycamore!” “That’s a sweetgum!” You realize they have personalities." Misha Semenov Photo.

"When you suddenly realize the trees have names and they have characters the way that you walk around New Haven is very different. You’re like: “Oh, that’s an elm tree!” “That’s a sycamore!” “That’s a sweetgum!” You realize they have personalities." Misha Semenov Photo.

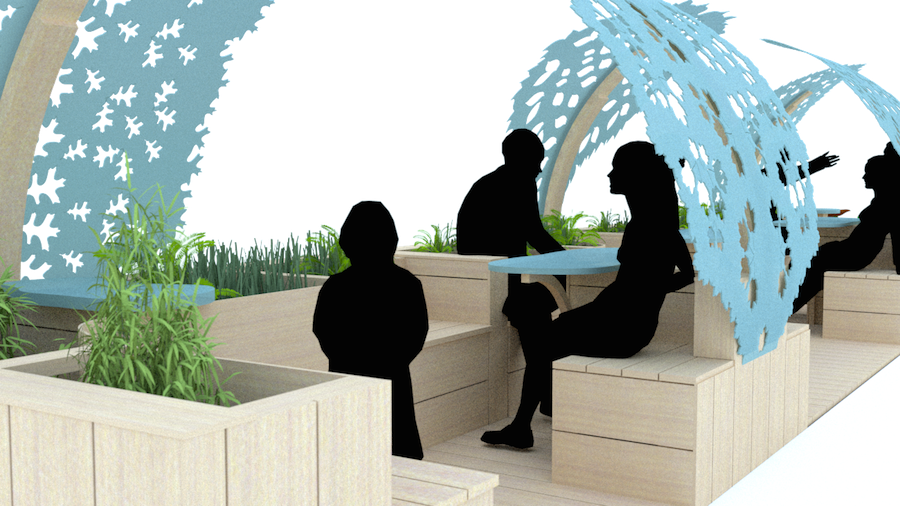

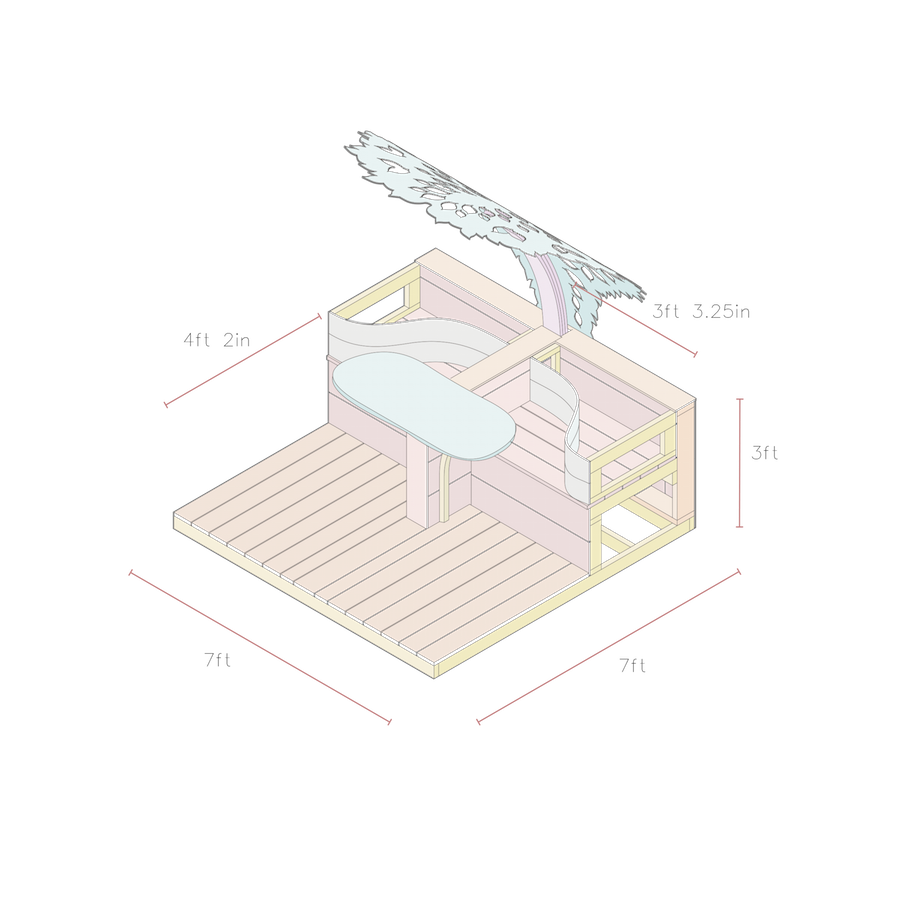

Yale School of Architecture student and co-winner of the New Haven Parklet Design Competition Misha Semenov was hard at work at Kent Bloomer Studio in Erector Square on Friday. Two high school students with Emerge YouthBuild—a Connecticut Department of Labor professional development program—had joined him to help assemble modules for his multi-functional “Urban Canopy” space.

The finished parklet will combine seats and tables, bike racks, edge planters, and adaptive LED displays into a venue for environmental education. The Arts Paper caught up with Semenov on his lunch break to learn more about the initial pitch and how it’s been putting his plans into practice.

Just for the benefit of our readers: Could you tell us who you are, what schools are you affiliated with, and then go into your passion, your motivation. What encouraged you to apply for the New Haven Parklet Design Competition?

My name is Misha Semenov and I’m a third year graduate student in the Schools of Architecture and Forestry in the joint degree program. What that means is I try and think through how architecture can help us renegotiate our relationship with ecology.

Misha Semenov at Erector Square. Stephen Urchick Photo.

Misha Semenov at Erector Square. Stephen Urchick Photo.

My life and work partner Kassandra Leiva is a second-year in the School of Architecture. Together we started—last summer—a larger set of inquiries called “The Ecoempathy Project,” which is trying to probe into how architecture can help us create empathic connections to nature. How can we design buildings that make you feel connected to the natural world? Or: Make you understand natural phenomena in new ways?

We were writing a lot about that, looking into a lot of different precedents, and how we might be able to express it and make that an actual project. I had just finished the introductory course at the School of Forestry, which involves a bunch of tree identification.

Ah, okay, with the New Haven Land Trust.

Um.

Or—not the Land Trust—the—

URI.

Urban Resources Initiative.

Yeah. So, tree ID opens up a whole new world! Because when you suddenly realize the trees have names and they have characters the way that you walk around New Haven is very different. You’re like: “Oh, that’s an elm tree!” “That’s a sycamore!” “That’s a sweetgum!” You realize they have personalities.

Obviously there’s a scientific aspect to them: Where does one grow? Where does one do well? You start being able to read things in the urban landscape. As architect I do this all the time. But for trees—now I know what they’re called!

When we heard about the Parklet Competition we got really interested in creating something that would help people feel that same way about street trees. That would make people who might not think much about street trees connect to them in a new way. We take these street trees and we make them into real personalities. We take them down to human size. We get people to relate to them and then spark, hopefully, interest in ecology.

We have five tree species of New Haven: the oak, the maple, the sweetgum, the elm—of course, you can’t do without the elm—and the plane. We have these canopies and they’re creating the shading structures that you sit under. As you’re sitting, you’re getting the shapes of these leaves projected onto your own body, onto the surfaces around you. So, you’re able to interact with these trees in a new way. With real trees you can’t see the leaf shape because there are so many of them. We’re trying to abstract nature just enough to make it legible.

—magnifying the five tree shapes by making them slightly larger-than-life, and allowing them to project onto somebody’s hand, or arm, or jacket?

Exactly! That’s the general idea behind it. We wanted it to be an object that emphasized sustainability. And, actually, I hate that word. Don’t use it—it’s a stupid word! It emphasizes the fact that we have to keep taking from as opposed to living in harmony with the earth. I prefer the word “regenerative”—being smart and frugal about materials. In this case, we are getting all our wood from reclaimed lumber. So, some of it is from Coney Island, some of it is from Connecticut.

What were your Connecticut sources of materials?

Armster Reclaimed Lumber. All the cladding, decking, and glue lamination is white oak. That actually is coming from City Bench, which takes street trees and processes them into furniture. These trees are not from commercial forests! I mean—obviously—originally the reclaimed wood was, yes, but it’s been reused. That’s really exciting for us.

There’s also the community aspect. We’re really interested in developing an environmental education program with signage around the parklet.

The last task is really exciting: We’re working with an engineering student to design an LED system that’s going to be battery operated. It will basically respond to various ambient conditions. Each tree will represent a different aspect of the environment: temperature, humidity, pressure. They’re actually going to change colors and glow differently. The LEDs are going to react! It’s part of this idea that trees are doing this all the time. We can’t see them do it, so this is—again—a way for us to empathize with trees by making these abstractions.

Would you mind talking about what specific part of the project you were working on today? It looked like you were doing some framing, starting to put together platforms for benches and structures.

You saw the bench outside? That’s one module. We’re building five total. Each module hosts a tree. So, that guy is going to host an elm. And these two are going to be two more modules. These are the base framings. Once we put those together, we can start assembling the benches on top of that.

Now, you were working with three high school students—or, I guess—two high school students and their supervisor from Emerge YouthBuild. Could you go into detail about how you got connected with Emerge YouthBuild and then describe more broadly this army of volunteers you seem to be marshaling from across the greater New Haven region?

I wish it were an army!

Well, it was like two families, right? From Fair Haven, or something?

Yeah, yeah, yeah! Most of our volunteers are friends. Thank God for nice people. Very few from the School of Architecture—because they’re too busy—but Forestry and PhD programs. People who have slightly more normal lives.

Right!

But, yeah—the great thing is URI is our fiscal sponsor and we got them to send out some important newsletters. So, we got some sign-ups that way. We’ve gotten plenty of people through various random newsletters and me being like: “Hey, can you please send this to your whole list!” That’s how we got this awesome family from Milford to come join us. There’s a family from New Haven. It’s been really rewarding. I think, in some ways—um—it’s hard having to retrain people every time they come in.

Yeah, I was about to ask. Real talk: Would it just be easier, on a daily basis, to be there with you and Kassandra—alone—in the workshop, plugging out several frames a day? Or is it perhaps easier to have a group of high school students, or a couple, or a family?

It really depends. A lot of it comes down to management. You have to figure out what tasks you can do, and then give them those tasks and not have them do something beyond them.

You did mention it was rewarding. Is that what keeps you reaching out for partners?

Yeah! It’s really rewarding to have people come in who have never done glue lamination. We teach them how to glue laminate wood and they go back home and say: “Wow, I can do this myself!” So, hopefully it’s inspiring to them. It’s especially great when you have people from this community who are coming here to learn those skills. I think it’s really great that it’s a project that everyone is going to see. It’s going to be public and publicly owned. It’s really something that everybody can take ownership in.

What’s one of the ways people have taken ownership of the project?

That’s a great question! I think the volunteers who have come have really gotten involved and dedicated to different parts of it. They’ve been great! People from the Chatham Square neighborhood—like Lee Cruz—got really excited about it, and have gone above and beyond to connect us with the right people to make sure the community receives it right.

And then, the people who are here! Kent Bloomer Studio [“KBS’] is incredibly generous to let us use their space. We have so much crap, and we’re using their tools, and they’re just doing it because they’re kind people.

Tell me the story of that: How did you get connected with the studio? What was that conversation?

Kassandra worked here last summer. And I TA for Kent who teaches at the School of Architecture. So, we sort of just convinced our way in here.

—you generated enough goodwill through the internship that Kassandra did and the TA-ing that you did and he thinks it’s a noble, virtuous endeavor?

Yeah! I wish Yale was more supportive. Unfortunately, Yale is too legally bound.

Interesting. Tell me more!

So: If we were to do this on Yale property, you would have to have a supervisor who we’d have to pay 40 bucks an hour whenever we’re using power tools. None of our volunteers would be able to use power tools. Not to mention: They were going to charge us $4,000 to use West Campus space. If we had been more persistent about it, we could have gotten it down and negotiated something. But the fact of the matter is: Going to West Campus every day—?

Here we have expertise, we have tools. If someone—if KBS doesn’t have something—Dana [Scinto], the woodworker down the hall, there, is amazing. She has really taken ownership: you asked about it! She was like: “You guys are doing glue lam, let’s do it together!” We could have never done it without Dana.

Huh. West Campus is this sterile space that charges you too much and has restrictions on volunteers. But: You come out to Erector Square and you have the woodworker next door and this studio helping you out. Not to mention: The volunteers from New Haven—some driving in from Milford! There’s a less sanitary, more kind of vibrant network of people, here.

It’s a little crazy. It’s like a big organized mess. And that’s kind of how things work! We really couldn’t do this project without people like Dana or Kent. They’ve put a lot out there.