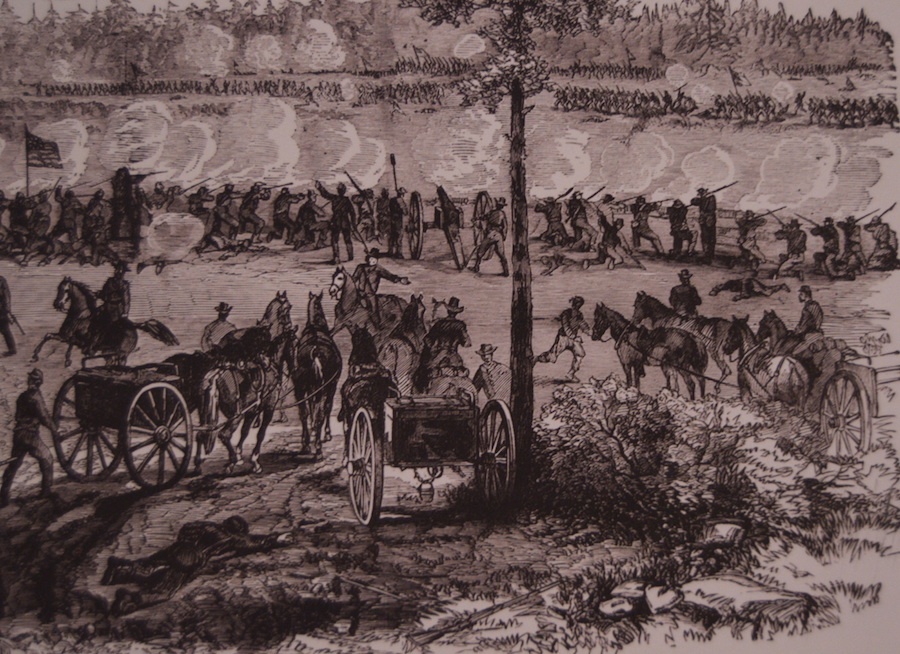

A detail of the of the illustrations. Karen Marks Photos.

A war artist stood at the war front of a skirmish, hastily trying to sketch out the violence and heat of the moment. He was not a soldier, but wondered if he would survive the war. He leaned in as much as possible, for the sake of delivering images of the Civil War to American people.

The illustrations are part of Making America: the Irish in the Civil War Era, running now through Oct. 28 at Ireland's Great Hunger Museum (IGHM) at Quinnipiac University. The exhibit contains drawings from Irish-American war artists who traveled with the Union army.

It begins with the history of Irish migration to the United States. In the mid-19th century, Irish refugees fled the Great Famine and found themselves landing in the American Civil War. At least 150,000 Irishmen served in the Union forces, and 20,000 with the Confederates.

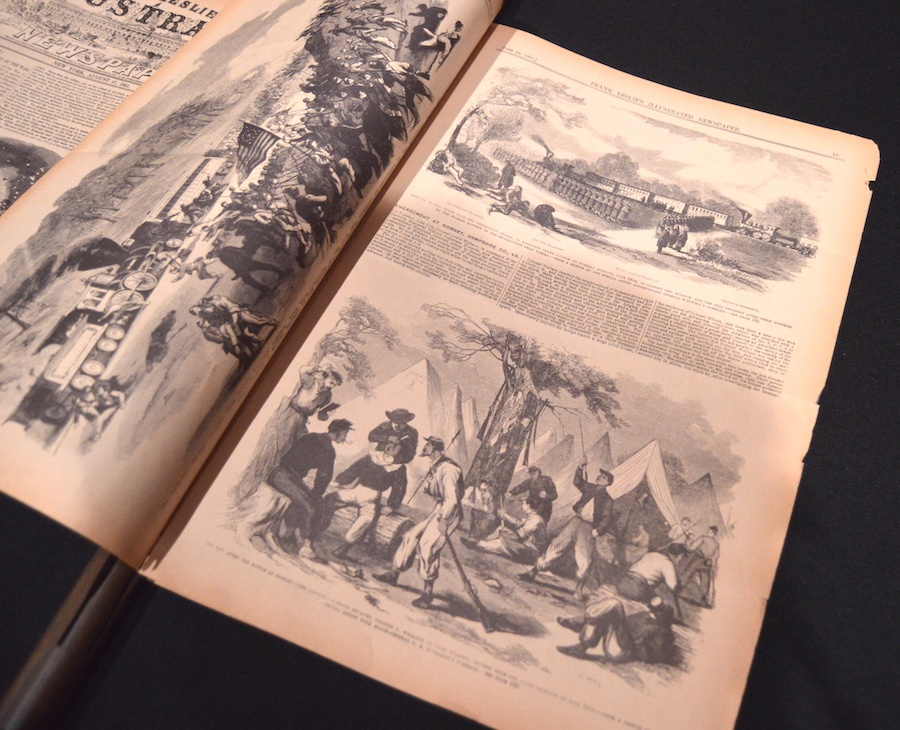

Among these Irish-Americans involved in the war effort are the artists featured in the Becker Collection on loan at IGHM. At a time when photography was not yet advanced enough to clearly capture movement, publications such as Harper’s Illustrated Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper sent “special artists” as war correspondents to draw scenes of battles, camps and marches during the war.

As members of American society that could not fit in with Anglo-Saxon Protestant ideal and were often subjects of xenophobia, Irish-Americans could act as allies to the Union forces and African-Americans.

In Joseph Becker’s drawing of “The Coloured Race Dancing and Gambling,” the artist does not take the opportunity to depict the subjects as minstrels. The Black Union soldiers at camp are not wearing dramatic finery or tattered clothing — typical of vaudeville images — and Becker’s rendering of the the audience around the campfire keeps the viewer from becoming the sole audience of a caricature performance.

If some Irish-Americans could find solidarity with African-Americans, it still seemed to many of these artists that taking part in the war effort could make an immigrant American. Both enslaved and free African-Americans also kept Irish-Americans from the absolute bottom of the American social pyramid.

Another drawing of Becker’s, entitled “Army ‘Washerwomen’,” pokes fun at the subjects — Black enslaved men performing laundry and cooking tasks for white Union soldiers after being confiscated from their Confederate masters as “contraband.”

The labeling of the Black enslaved as “contraband” enabled the Union army to free them from their Southern masters without violating the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which would otherwise require the enslaved to be returned to their masters. While in effect “freeing” the enslaved from their former masters, “contrabands” performed a large part of the labor force for the Union army. Aside from being jokingly labeled “washerwomen” for the sake of Becker’s drawing, “contrabands” were also seen as competition for Irish laborers in the Union army.

The illustrations branched out to include drawings of Confederate prisoners, the execution of deserters, and an exhumation of a soldier’s body entitled “Something to Coax the Appetite.”

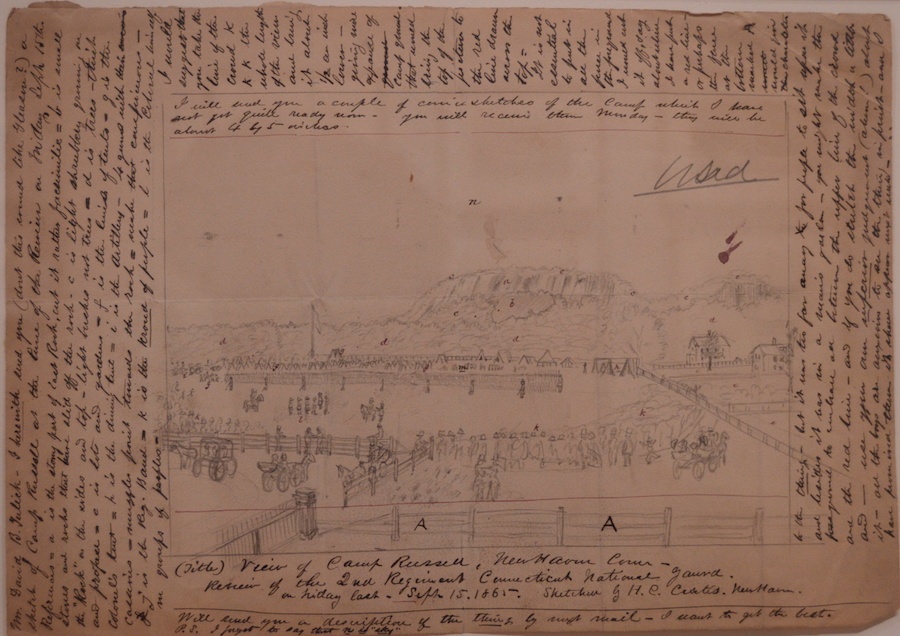

Drawings made in the heat of battle — or the risk of one — were often roughly sketched and then labeled. IGHM provided examples of the artists’ drawing studies — rough sketches labeled, re-rendered, and returned with notes from “editors” along the journey of becoming a complete rendering of the war front scene.

A drawing of Camp Russell, located at East Rock in New Haven, moved images of large trees where they overwhelmed the image and tightened the horizon. Dense notes along the margins said, “I would suggest you take the line of the crowd the whole length of the view and bring it lower.”

Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper had a large staff devoted to printing these wartime illustrations. The paper had the most special artists out in the field and 120 craftsmen to engrave the drawings for print, so the illustrations — dense edits and all — could be turned around quickly. IGHM also has replicas of the paper on display, showing how the hard work that had gone into the illustrations took up whole papers, with the text crowded into the other folds to make room.

As the years of the Civil War passed on the museum walls, images gave way to the New York Draft Riots — fueled by Irish New Yorkers who resented what could be perceived as a war for African-Americans — and the decisive battles that finally turned the tides of the war.