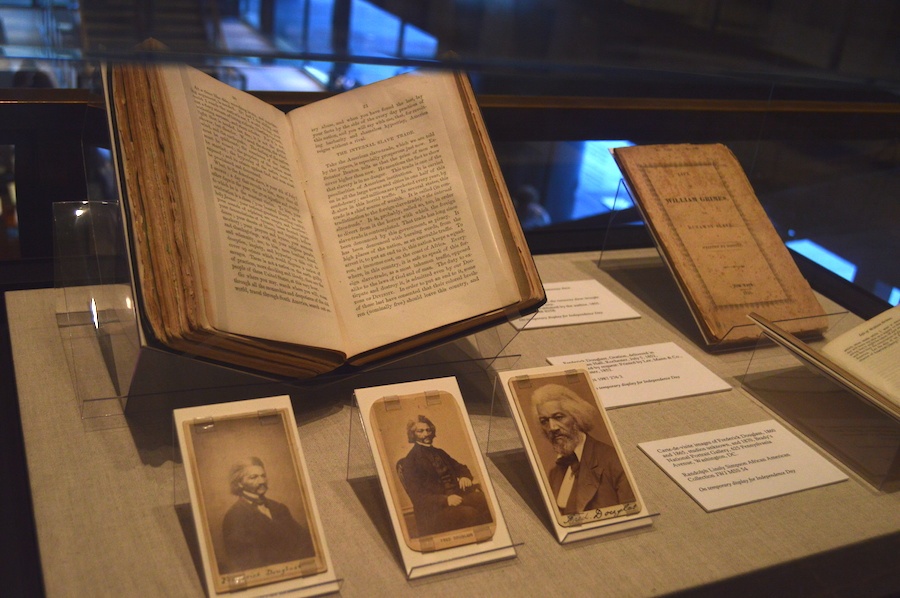

Prints of Fredrick Douglass' address at the Beinecke. Karen Marks Photo.

Trina Lucky stood behind a podium, her voice pounding against the marble walls of the library. She was one of ten speakers taking part in a public reading of the United States’ founding document — the Declaration of Independence — and an hour-long address that questioned who was really declared independent in America.

On Thursday, the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University hosted a reading of the Declaration of Independence and Frederick Douglass’ oration “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” The podium was set yards away from an original printed Declaration that was sent throughout the thirteen colonies for republication in July of 1776.

Beinecke Communications Director Michael Morand kicked off the program and recounted overhearing a family consider the display’s relevance to current politics.

The Declaration of Independence was read first by two readers Lisa Monroe and George Miles. Another reader, Tubyez Cropper, began reading Douglass’ oration immediately after, making a seamless transition that encouraged the listener to hear these moments of American history as inseparable.

"It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom,” Douglass told the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in 1852, knowingly excluding himself from the celebration. “This, to you, is what the Passover was to the emancipated people of God.”

Douglass tells his listeners that 76 years is young in the life of a nation; the currently existing nations (empires, then) numbered themselves by thousands. However, he emphasizes how in its short life, the free people of the United States have praised the good deeds of their forebears while covering up their own wrongdoings in their current time.

Seven readers later and at the end of a nearly hour long address, Douglass reminded listeners that “precisely what I have now denounced is, in fact, guaranteed and sanctioned by the Constitution of the United States.”

The consecutive readings reminded listeners that injustices against Black Americans specifically were not a careless blindspot in the nation’s founding documents, but in fact their foundation. While reading a section of the Declaration of Independence, George Miles’ voice recited King George’s neglect of the colonies to “merciless Indian savages.”

Listening to Douglass’ address read by Black and white readers alike, one could remember that complaint and think — “What to the Native American is the fourth of July?” Douglass believed the end of slavery was definite but still spoke on the reality that enslavement and oppression were the basis of the United States government.

Civil War historian David Blight ended the oration and stayed at the podium after the applause that echoed around the Beinecke library. He reflected on a quote from the end of Douglass’ second autobiography.

“‘My voice, my pen, and my vote,’” he read. “That’s about all any of us have.”