| Martha Willette Lewis in April 2020, showing pieces from her Quarantine Cinegram series. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

This is part of a new series of interviews with New Haven artists about the U.S. Census. In installments, artists answer the same questions about the Census, which determines the amount of federal aid allocated to New Haven. To read more of these interviews, and learn about the role artists are playing in New Haven’s census effort, check out the Census 2020 tag.

Martha Lewis answered the 2020 Census as soon as a notice arrived at her house. With one month to go until census counting efforts ends around the country, she’s urging others to do the same.

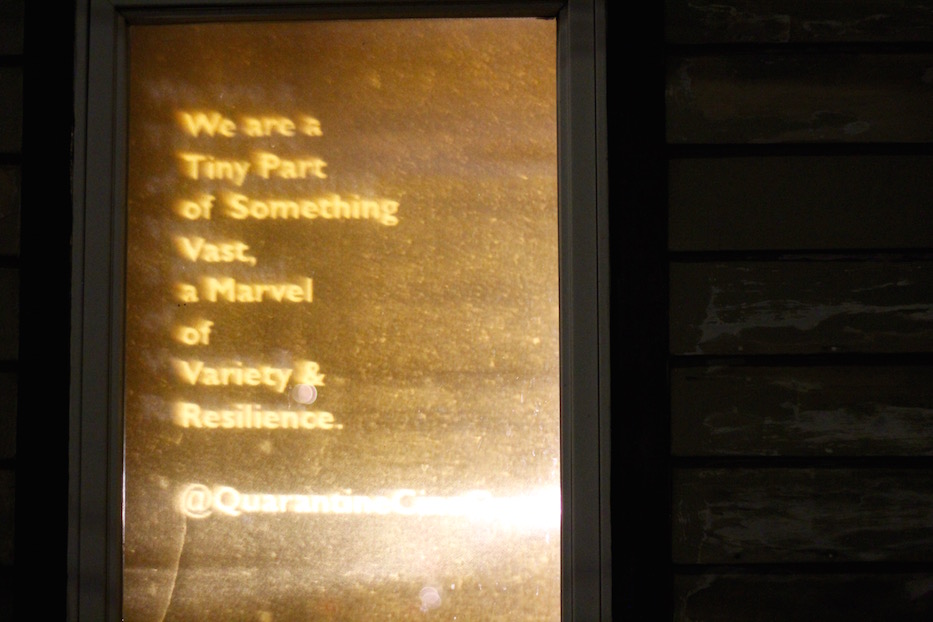

Lewis is a multimedia artist and curator in New Haven, where she works out of an Erector Square studio and her East Rock home. This fall, she is curating Declaration of Sentiments, a show celebrating the centenary of the 19th Amendment, at the Institute Library downtown. During COVID-19, she has become known for her nightly Quarantine Cinegram series, in which short, often poetic meditations are projected in flickering orange from her Pearl Street window.

The U.S. Census Bureau has announced that it will stop counting census respondents on Sept. 30, a month earlier than previously planned. Held every 10 years and mandated by the U.S. Constitution, the census is intended to count every person in the country and collect data for the proper allocation of federal funds and drawing of legislative districts. In 2002, the state lost a representative in its fifth congressional district following a lower count on the 2000 census.

It also determines how much money each state receives from the federal government. In other words, it directly impacts New Haven’s access to Medicaid, Medicare, Head Start early childhood education, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) food benefits, and other essential federal benefits programs.

New Haven leaves roughly $2,800 on the table for every person not counted. In 2010, some 40,000 New Haveners were left out. In 2020, Mayor Justin Elicker has expressed a concern that undocumented immigrants, fearful of the Trump administration, will not fill out the census.

During her interview, Lewis also pointed to the importance of thinking about arts funding as part of the census; there’s a new question that now reflects it. An edited version of that interview is below.

| Lewis' Quarantine Cinegram for Earth Day. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

Have you completed the census?

Yes. I did it immediately. I think the census is incredibly important. It was a while ago now.

How do you identify personally and how did you identify on the census?

You mean, did I say white and female? I said I was white and female.

Did you find any challenges completing it?

It was a long time ago when I answered it, so honestly I can’t remember. But no, it didn’t seem to be a problem for me. I don’t know what it would be like if English was my second language, or a bunch of other things.

There’s an article in the New Yorker that’s meant to be humorous called "Please Don’t Answer This 2020 Census," and it’s full of these incredibly complicated questions that they’re pretending that you have to answer.

I don’t remember anything being particularly hard. Although, there were a couple things that seemed like they might be trick questions. There was something about [the number of] people staying at your house, and then they ask it again. They kind of ask it twice in some funny way.

Will this be the first census you complete?

No, but it does feel like one of the more important ones. The census has to do with how many representatives we get, allocations of funds for roads and schools and all the things that I care about. So to the extent that I believe that answering the census correctly is going to make sure that I get all of the things that I care about happening in my neighborhood, yes, it feels very important.

Because there are so many forces trying to take all of this away from us. Gerrymandering has been such a huge problem, and is one of the reasons we’re in the predicament we’re in right now.

Do you remember your first experience with the census?

No, because I’m antediluvian and that was a long time ago. I think I have a dim memory of my mother filling it out. My mother was a real joiner—followed rules and did what she was asked to do. It’s true that she would get angry if she felt that there was an injustice in her face, but she was not a person who—neither of my parents talked about politics particularly much. I learned about politics from other people when I was growing up.

Where did you first learn about the census?

Boy. I’m going to assume that it was in school, in something like an American history class.

What do you think people in your family or immediate community think of the census?

What do my family members think of it now? I don’t have enough family to answer that. They’re not here to think about it. I would say that the people in my family, towards the end, were incredibly politically engaged and would consider it your moral obligation to do it.

I think that they would also say that there are good reasons for immigrants to feel nervous about it, because of the underhanded way that this current administration deals with data and information. I do think they would get why people might feel suspicious about it. At the same time, it goes for longer than this current administration if we’re gonna get this current administration out. So let’s just have a little faith and go forward.

As far as the impact on my local community, I live in a part of New Haven that is full of people who … it’s a little bit of an echo chamber. People probably already vote and we probably mostly agree. There’s a couple of people who I politically don’t agree with who are actively posting things at the end of their street, but pretty much everybody in my neighborhood is probably onboard with this already.

There are a bunch of younger people, who I’ve always pegged as graduate students, and I honestly don’t know how engaged younger people are. But I feel like they ought to be engaged.

Do you feel like there is a distrust around the census and the government collecting information at large?

Absolutely! Absolutely. I think that people have a good reason to mistrust the uses of these things. Their trust has been abused many, many, many times, and there are organizations and people who spend all their time trying to break in, grab your data, do this with it, do that with it. There’s an incredible amount of fear and anxiety attached to it because it is, in fact, really hard to keep it secure. If not impossible.

Does that mean you shouldn’t do it? Consider what they’re going to do with your data, exactly. So, it depends on what happens, I guess. If we truly go into a fascist state, yes, I suppose people could be rounded up. Which would be the worst case scenario, and which I think is what people are afraid of. And they could also be harassed. I guess I could come up with all sorts of awful scenarios where people are harassed, the IRS is doing things to them, stuff is made up about them, they have all the data and can do all of these things.

Were there myths about the census that you heard growing up?

You know, I kind of remember old movies and television having things with census workers sneaking around the outsides of houses, or posing as census workers to get in. You know, like in old Film Noir, people are constantly knocking on doors or pretending to be something or other that they’re not to get information.

How do you think the census could be improved?

Well, obviously people’s trust in it is the central issue, right? We’ve spent a lot of time talking about that already. I think that the things that I’ve seen online suggest that there’s more than one group and more than one reason that people are feeling mistrustful about it.

There’s people who feel like their privacy is their privacy, and their property is their property, and their guns are their guns, and they’re not going to answer any damn questions. And they don’t care about taxes either; they don’t believe in taxes. So you get that group. And then you get the group of people who are disenfranchised, disempowered, afraid, maybe they don’t understand exactly what the collective goods of answering the census are.

I think that the government needs to do a better job of proving to all of us what the collective goods they get out of it are. And why we’re safe in giving them this information. It’s interesting: it’s okay to mail in your census form but it’s not okay to mail in your vote.

I think that if there were any work to be done on the census, it would be proving to people that they have a vital interest in answering it fully and accurately, and that there are some real, direct benefits that they would get out of it. I do it on the possibly naive trust, because of what I’ve been told is what I’m going to get out of it.

I don’t remember if the census comes in multiple different languages [it does], but that would be the obvious thing to do. To make sure it’s multilingual.

What would you like to be included in the next census?

I think I care less about the census as a kind of questionnaire as I do as a kind of means to getting state representatives and getting the collective goods that I want. So I guess it would be nice if they asked us what collective goods we wanted, and to front load it a little bit more that way. For instance, I would like less money going towards the military and the police and more money going towards schools and libraries.

It would be nice if I felt like what my concerns and wishes were were taken into account. And that state representatives were forced to look at the statistics of what we all wanted. I think more accountability is what I’m getting at.

What would you tell people who are skeptical about filling out the census?

I’d tell them that it’s not about the now. It lasts for 10 years. It’ll be 10 years before we get another one. That means that it seals the fate of how many representatives we get and how our tax money is apportioned. And that if they care about any of these things, and I would then go into detail about what the tax money is supposed to be going towards, it would behoove them to show interest in it and to put aside any fear that they might have.

That this is not about you. It could be turned against you, yes, but honestly everything could right now. Like, we’re all data breached ourselves so much on the internet that there is nothing that they’re finding on the census that they don’t already know. So that’s the other thing. Lose your fear! You’ve already given up the ghost.

The census involves tax money and dictates where our tax money is going. In an imaginary world where we’re all talking about where our tax money is going, how do the arts figure into that?

One of the more horrifying things about this moment is that obviously, tourism is down for a long time. And the main argument for funding arts in Connecticut has been the tourism revenue. We all know that since the start of COVID-19, all we’ve bee doing is sitting around consuming art, making art, spreading art around, sharing it. Art is what is allowing us to survive. So I think we need to front load that message and figure out a way to monetize it. Which is pretty hard, because most of it is being done just because we want to survive.

The arts are like air. They’re like glue. It’s what we spent all day long doing. Not just artists—this is the thing people don’t seem to realize. It needs to be funded in a broad way, because that’s how people learn, grow, relax, entertain themselves. My definition of art is pretty broad, so it’s more like culture. It can be a kind of therapy. It can be a way of talking about things that are difficult to talk about. It can allow us to think new thoughts, it can allow us to process information. It’s everything.