Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | West Haven | Arts & Anti-racism

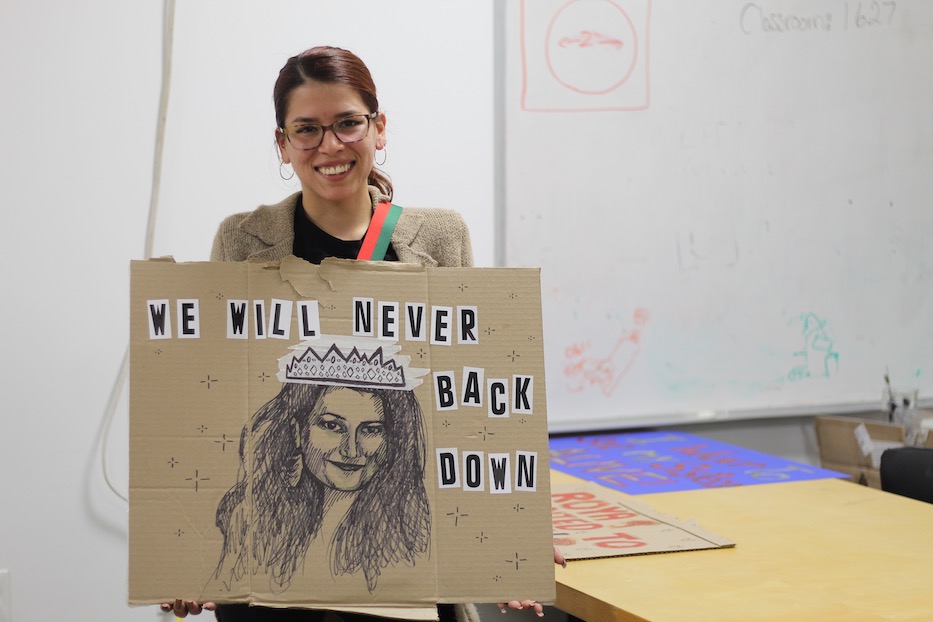

Vanesa Suarez with one of the posters from artist Jisu Sheen.

It's her eyes that stop a viewer in their tracks, full of warmth as they flutter open and light up beneath a crown. Beneath them, a smile dances on her lips; her hair flows down to her shoulders in a swish that looks regal and propulsive, as if there's a breeze. The words We Will Never Back Down float around her face, the letters clear as day in a sea of starbursts. She is so alive.

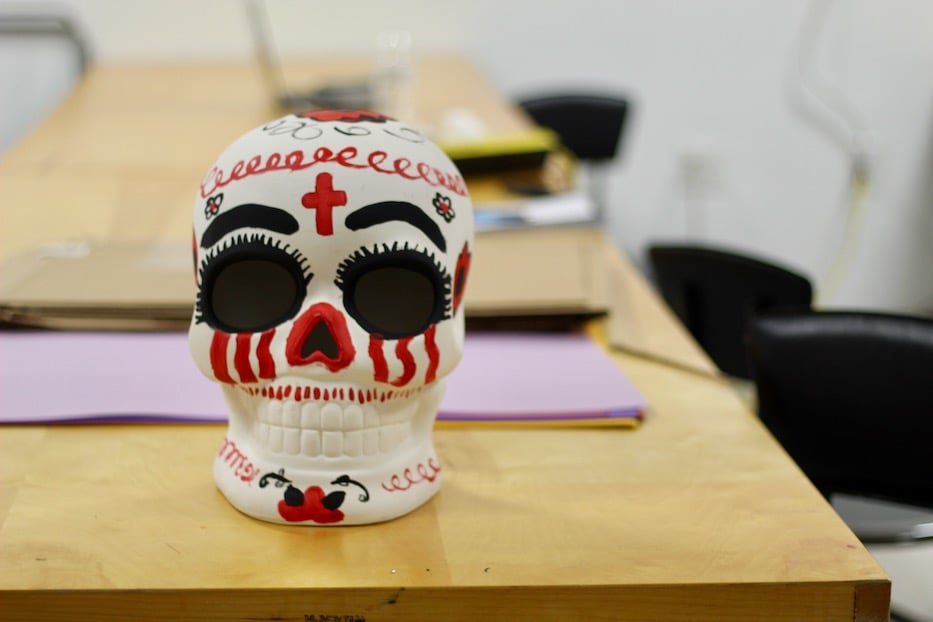

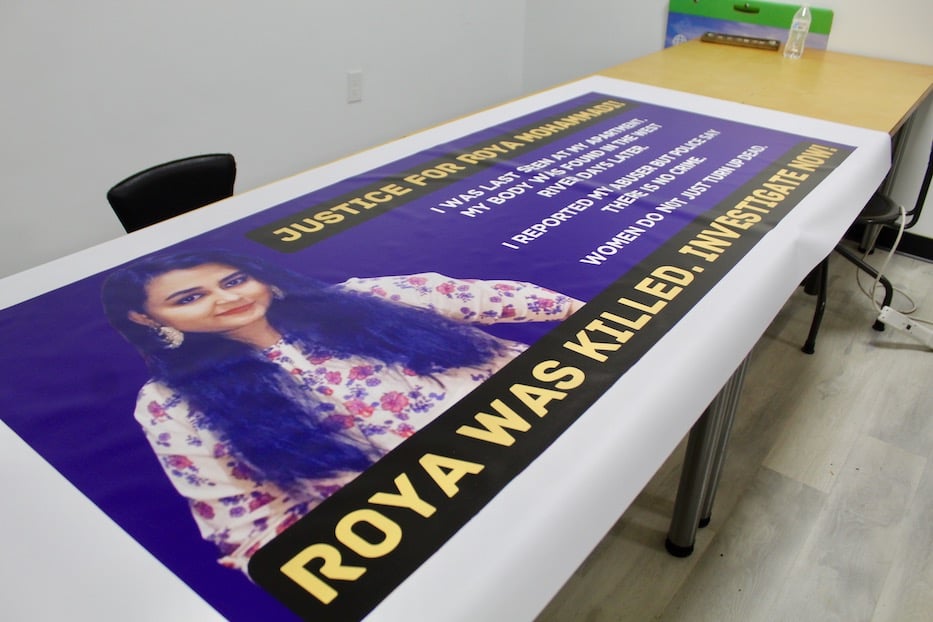

The face belongs to 29-year-old Roya Mohammadi, a translator, scholar, culinary artist, Afghan refugee and dear friend and sister who was found dead in West Haven in early March, just a day after colleagues reported her missing. Eight months after her death, advocates are calling for greater accountability from both police and public officials, who have remained largely silent. On Sunday, they plan to march through her neighborhood, carrying artwork that they have collectively made over the past three weeks.

The action—meant to celebrate her life and learn more about her premature death—centers collective artmaking as both a form of activism and a salve, helping advocates cope in the wake of a year that has felt impossibly violent.

"There is an attempt to erase Roya from her neighborhood, and I want it to be a norm for a community to take up space and call for justice," said Vanesa Suarez, one of the founding and most vocal members of the group Justice 4 Roya, in an interview at MakeHaven Tuesday night. "It's just a reminder that even when women are believed, the system is so flawed that it is set up to fail us. And what are we left with? We are left with the same system and the same laws."

Advocacy around Mohammadi's case has been building since March, when her body was discovered in the West River a day after her colleagues at Havenly reported her missing. In the days and weeks that followed, friends and colleagues connected with her family members in Afghanistan, continued to raise awareness around her case, and pressed the West Haven Police to disclose more information around the circumstances of her death.

During her time in West Haven, Mohammadi made several documented reports of domestic violence to the West Haven Police, naming the same family member each time. As of this week, no arrests have been made in the case, and no person of interest has been publicly identified. Her siblings, who are in Afghanistan, say their statements to police have been largely ignored.

Sgt. Patrick Buturla, public information officer for the West Haven Police Department, did not have any updated information on the case when reached Friday by phone. He said that he would check in with the department Friday and again over the weekend to see if there was new information.

For Suarez, who is a survivor of sexual abuse and has called for stronger measures against femicide in Connecticut and across the globe, the process has felt like a horrific case of déjà vu. In August 2020, she and others began to call for an investigation into the death of Lizzbeth Aléman-Popoca, a 27-year-old East Haven mother whose common-law husband has since been arrested and charged with her disappearance and murder. She has struggled watching that trial play out, she said—in part because police took so long to press charges, and in part because any sentence will not bring her back.

When Mohammadi's body was discovered in March, the similarities were chilling to her. Both were immigrant women—one from Mexico, one from Afghanistan—in their late 20s, adored by those who knew and loved them. Both had gone missing days before police began to look for them. Both have become the subjects of investigations that go unsolved for months and are mentioned seldom in the news, while their white counterparts make prime time.

It made Suarez think of the long and growing list of women—often Black, Latina, and Indigenous—killed and disappeared in acts of domestic and intimate partner violence in Connecticut alone.

"I don't think they would have looked for Roya's body," she said Tuesday. "Roya was found because people who cared about her reported her missing."

"When we die, no one cares about us," she added, invoking the names of Lauren Smith-Fields, Brenda Lee Rawls and Rickeyta Shantise Baker as she spoke. "And that's really devastating ... the way it cripples our families. The kind of harm that's created."

In the thick fog of that trauma, she added, the artmaking sessions around Sunday's action have been a way to create a space for healing. For weeks leading up to the march, Suarez and fellow Justice 4 Roya members Nika Zarazvand, Camila Güiza-Chavez and Jeniffer Perez-Caraballo have held hours-long workshops at MakeHaven, filling the space with paint and brushes, markers, papers, cardboard, and other art supplies.

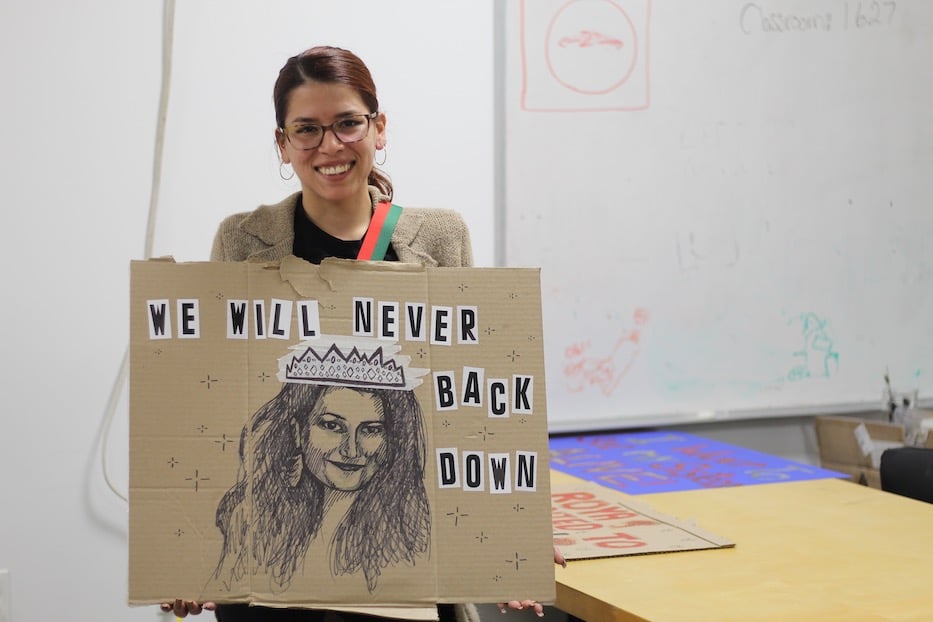

As the room fills with conversation, Suarez said, it helps double as a balm and a reminder of community—that no one person is going through organizing and justice work alone. While the march was originally planned to coincide with the Day of the Dead—it was moved last week in solidarity with global actions for Palestine—she added that she likes the idea of normalizing calls for justice in neighborhoods and civic spaces.

"I think it's how we dream," said Suarez, whose photography from Chiapas, Mexico has also addressed femicide and self-governing, matriarchal systems of power meant to protect women when laws and governing bodies do not. "It's in the words that we share with each other, the dreams that we share. Organizing is very, very heavy, and what I've told myself coming out of that [work] is that I want to change the experience for other victim advocates."

Artist and Fair-Side Founder Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, who attended a final artmaking session Tuesday with artist Jisu Sheen, pointed to the importance of a space dedicated to communal making, particularly in the name of social justice and a fallen sister. During her time there, she listened as Suarez and Zarazvand discussed a banner that Mohammadi's family had weighed in on before it went to print.

In the absence of words, art did the talking. It's the same approach she uses with Fair-Side, a community of practice that decouples praxis from capitalism and nonprofit institutions.

"I think art can hold vulnerability right?" she said. "I didn't know what to say, because there isn't anything to say, but the art we made was holding that space. It's a tool to hold all of that pain and put it towards what we collectively want."

"This power, this action and this energy reminds us, reminds me, that women are so loved and deeply cherished," she added. "And that includes me, and any woman who may be experiencing violence in any form. It reminds me that if I experience violence, my sisters will fight for me. It reminds me that I am safe, and that my sisters would do anything for me."

On Friday morning, Mohammadi's younger sisters, Shamim and Khalida Mohammadi, also added their voices to that chorus calling for justice (read two statements from her sisters in full here). Shamim, who is the youngest sister, said that police informed family members that they could not enter evidence into the investigation or report Mohammadi missing, and that "only residents could file a complaint or report someone missing."

She stressed that the family believes that Mohammadi would still be alive had police taken her initial complaints of domestic violence, taking place in the home she shared with an aunt and uncle, seriously.

"I have no doubt that they should have protected Roya's life first and foremost when she had reported her abuse," she wrote in a statement sent to the Arts Paper Friday morning. "Secondly, they should have investigated the circumstances of her death immediately after it occurred, and lastly they should have contacted our family to be in communication with us directly."

Khalida added that she thinks often of how many of her sister's dreams—indeed, how her sister's very capacity for dreaming—was cut short earlier this year. Even before she came to the U.S. to pursue her studies at the University of New Haven, Khalida said, her big sister dreamed of opening an orphanage and launching a music company, two hopes that she will never get to see.

"Roya's murder and her death wiped us out as a family and left us hopeless. We may be alive but we are no longer living," she wrote. "If Roya was alive, I am sure she would have achieved all of her dreams. Maybe it would have taken more time, but I knew that the day we reunited would make up for all the years she was away from her family. We live without her embrace. We have spent dark nights and days without her and yet we are forced to continue living this damn life.”

Sunday’s vigil and march will begin at 2 p.m. at 25 Boston Post Rd. in Orange, Conn. and end on Knox St in West Haven. The march will culminate in a communal altar on Knox St. where Roya lived, with photos of Mohammadi and her favorite things—flowers, art, and decorations created by community members over the last few weeks.