Fair Haven | Photography | Politics | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Visual Arts | Arts & Anti-racism | International Women's Day

Top: Artist and activist Vanesa Suarez. Bottom: The spiral women made, which Suarez shot from above. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Thousands of women gather under the open sky of the Caracol of Morelia in Chiapas, Mexico. Their bodies stretch in unison. Their arms unfurl into the air and their knees press into the sun-bleached dirt. They are shaking, screaming, honoring, remembering. They create a spiral, in a ritual of ancestral dance. Each living body represents the life of a woman or girl that was lost to violence.

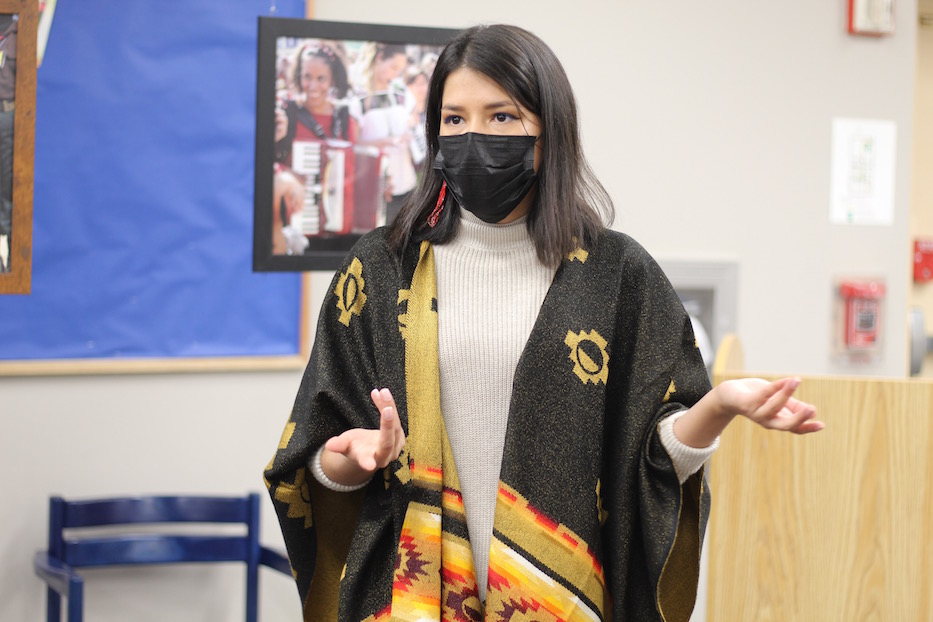

Standing on a raised platform above them, New Haven activist Vanesa Emely Suarez takes a photograph. She takes many. Her “sisters” back home in New Haven do not have the papers to cross the border or money to fund their trip. Suarez’ camera acts as a window, closing distance and time.

The scene—captured through Suarez’ compassionate and sharp eye—is now part of Women Who Fight, an exhibition and project based on her visit to the second International Gathering of Women in the Caracol of Morelia, Chiapas, Mexico in December 2019. Last Saturday, she installed several of the photographs at the Fair Haven Branch of the New Haven Free Public Library for a one-day exhibition. Two dozen attended the show.

The body of work uses art to speak to survivorship of violence and sexual assault—and literally pictures a journey toward personal and collective liberation. In addition to 15 framed prints, Suarez has made a book of photographs that was on view last weekend.

"We have a right to live,” she said Saturday, switching between English and Spanish as she addressed viewers at a small reception. “We have a right to fully live our lives, to grow old. We have a right to mess up. We have a right to wear what we want to wear, to say what we want to say, to be what we want to be—and yet we don't feel like those ways. But it was a reminder that we have this freedom, that we have this autonomy."

Suarez’ work in art and activism are intertwined. In her teens, she became a survivor of sexual violence and assault—an experience she has spoken about openly multiple times in and beyond New Haven. By then, she was already an artist and an organizer for immigrant rights. For a three-to-four-year period, she sought recognition of and reparation for the violence she had survived in court. The process brought her the opposite of healing.

“Going through a process like that sort of reminds you how alone you are in the violence—that it happened to you, and just you,” Suarez recalled Saturday. “And that can be so hard and heavy to carry, even when you’re tapping into your power of being able to tell your story.”

In art and organizing, Suarez opened a path to healing. She made paintings, often of nature, to depict her inner struggles. She also continued to organize. As an organizer in New Haven, Suarez, who herself is a Peruvian-born migrant, works with undocumented people in Connecticut and people detained by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). She has also mobilized for women experiencing violence.

The Second International Gathering provided her with an additional avenue for healing.

That journey began three years ago, when she boarded a plane for the gathering, a three-day event hosted by the Indigenous Zapatista women in the Zapatista autonomous territory of Caracol of Morelia. Zapatistas currently run five autonomous Caracoles, or municipal groups, in the mountainous Chiapas region. Starting in 2018, they opened their territories temporarily to women as a safe gathering space. In the first year, 9,000 women and girls attended. The second year brought in 4,000.

While she had gone alone in 2018, and met up with Hartford-based artist Constanza Segovia once she arrived, Suarez attended the 2019 gathering with several sister-activists, including New Havener Hazel Mencos and an Atlanta-based organizer and co-conspirator for whom she volunteered to translate. She later added that it was important to her to bring more Black, Afro-Latina, and Afro-Caribbean voices into the space, regardless of their language ability.

She arrived, just as she had the year before, to a place that has essentially eliminated violence against women. The Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) is an armed resistance group whose membership is primarily composed of local Indigenous people. The EZLN is opposed to neoliberalism and the colonial violence toward and exploitation of Indigenous people of Mexico. For three decades, members have curbed violence on their land largely through peaceful direct action, with steps like the prohibition of alcohol (which is directly tied to partner violence) and facilitated conversations around partner violence and community safety.

Between the first International Gathering of Women in 2018 and the second in 2019, the rise in global violence against women coincided with the decline of that in the Zapatista community. Suarez pointed to how the Zapatista women centered this violence and its aftermath in the second gathering.

“[The Zapatista women] could celebrate that not one single woman had been murdered, had been disappeared, of the thousands of Zapatistas in their community,” she said. “And yet they held that victory with so much pain, looking outside, looking at all of us coming from around the world, that we could not share that victory, because in our communities, women were being killed.”

Nika Zarazvand, a fellow artist and activist in New Haven, who described the context around Rojava during a short question-and-answer session. Suarez said that one of the best parts of attending two years in a row was being able to see the public art that she and fellow women had worked on the year before.

On the first day, called “denunciations,” organizers invited women to walk onstage one-by-one, and share their stories of survivorship. Onstage was a single microphone, connected to a speaker system that stretched for miles throughout the camp. Suarez recalled hearing the women’s voices even while she was away from the central gathering, using the bathroom. As scores of women took turns speaking, their voices reverberated across the territory.

The women's goal was not punishment or reparations, she said. There were no law enforcement officers, judges, or juries present in the audience. Rather, the objective was to speak—and to be heard. The women cried, screamed, and yelled. They also comforted each other. Suarez remembered approaching the mic to tell her story, and feeling “so nervous,” and then genuinely heard for the first time. Even after a successful trial, she said, she had never fully felt empowered or believed.

“I was like, ‘Well, this is millions of strange women,’” she recalled. “I will do what the Zapatistas say. I will cry with them, because I need to cry, right? I will yell with them because I’m angry that this happened to me. I will go up there and take up the space that my soul needs to take up … nowhere else has someone said, ‘Do what you need to do. Cry. Scream. Do what you need to do.’”

She spoke about how much trauma she had faced as her trial dragged on for three, then four years. She spoke about the pain she still feels when she saw violence toward fellow women. She spoke honestly about feeling broken, blamed, and questioned, despite having “won” in court. The response was what she’d been waiting for years to hear: she was validated. She heard screams of “I believe you” from the group. Fellow women celebrated her victory as their collective victory.

“It makes you really hold all of that pain in, and to really hear each other in ways that we don’t always really hear each other. And to really see each other.”

“There were thousands of women there who for the first time were learning to tell their stories. Who for the first time were learning what it was like to receive an ‘I believe you,’ to receive a ‘You did it,’ ‘You made it,’” she said.

While denunciations were meant to last one day, they lasted almost two. Suarez called it “proof of how many women really needed that microphone.” In part, she said, the women gathered knew that they would need the space to absorb and hold each other’s stories, because they would be returning to homes where violence against women was still very much a reality.

“To be surrounded in that for over 24 hours of just testimonies, it does something to you, you know?” she said. “It makes you really hold all of that pain in, and to really hear each other in ways that we don’t always really hear each other. And to really see each other.”

When they had finished speaking out, women focused on solutions that they could bring back to their own communities—New Haven and Connecticut among them. Attendees formed breakout groups, where they traded organizing wisdom and strategies for direct action. They spoke, they played sports, worked on public art projects, made music, and danced, using their bodies to communicate across cultures and language barriers.

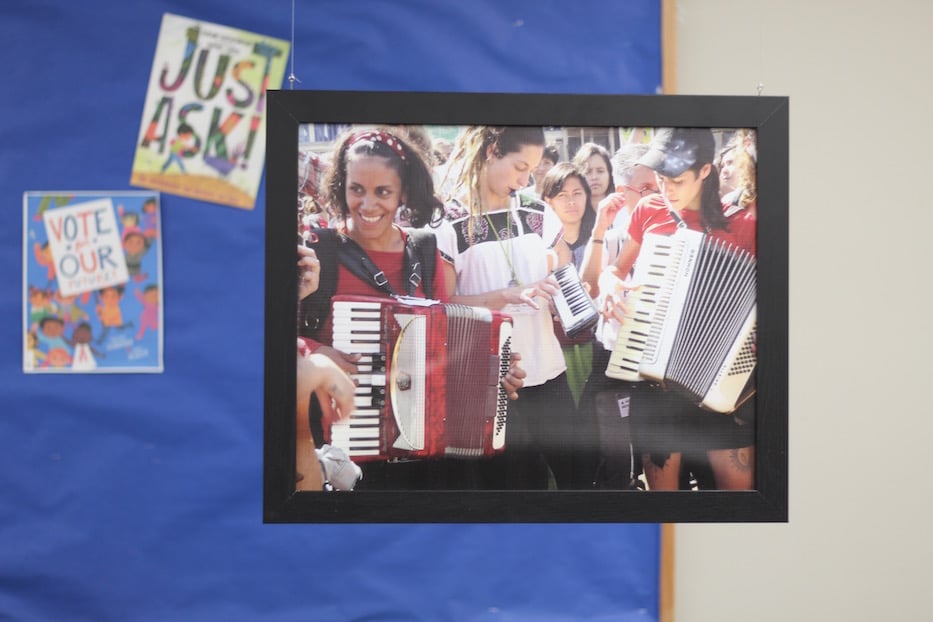

One of Suarez’ favorite photographs in the show depicts a group of women gathered around a tiny keyboard and two accordions, holding an impromptu jam session. She recalled wishing she’d brought her vihuela as women joined in organically. All of them listened, and then seemed to know just the right moment to step in.

Another photograph captures a Zapatista girl suspended in a moment of play. The girl’s torso is outstretched, and her arm winds back to throw a soccer ball onto the field. Like the grown Zapatista woman, the girl wears a black mask, which conceals her facial expression. But her physical movement clues the viewer into her attitude. There is a joyousness and freedom to the way she carries herself.

Suarez—who had no idea the pandemic was on the horizon at the time—loved seeing such a level of autonomy among children, she said. She later said that she wondered what would happen if all people wore masks, and had to communicate through only their eyes. Less than three months later, she found out.

Given Suarez’ goal of bringing the experience back home to her New Haven sisters, her 2019 photographs have a documentary quality–indexing the people, buildings, and objects that populated her experience. But they are also deeply feeling, a reminder that she is very much part of the sisterhood she is documenting. Saturday, that sense spilled over into the library, as kids colored at a table behind photographs, and Suarez walked two young girls through several of the photographs, answering every question they had.

In one photograph, a Zapatista woman stands in solitude. A green military-style hat sits atop her head, and a black cloth that wraps around her head and neck, shielding everything but her eyes. In her hands is a long wooden bow, with an arrow nocked into it. The woman’s eyes gaze into the middle-distance. She is on watch. Behind the woman, multicolored camping tents speckle the grassy landscape, nested around a building that is swatched in blue, red, orange, and green paint.

There is a solemnity to the way the Zapatista woman stands guard, and a whimsy to the community-driven art projects that surround her. The photograph captures the deep humanity of the Zapatista struggle, in which the Zapatistas have found it necessary to arm themselves against the state of Mexico and multinational corporations who seek to colonize their land and resources. The juxtaposition of art and weaponry suggest that both have been instruments of their struggle.

Another photograph provides a full view of a mural, which attendees have painted on the side of a building. The title, “Mujeres Que Luchan” ("Women Who Fight") is stylized in bold font, accented with red five-pointed stars. Below is an array of women standing atop a globe. There’s a diversity not only to the region which the women represent but also to which the form they take. Some are representational, with true-to-life features, and others are iconic, using imaginative shapes and colors to bring the image of a woman to mind.

One woman wears a burka and holds a sign that reads “Defend Rojava,” referencing the Kurdish autonomous region in Northeastern Syria. To the woman’s far right is a woman in the form of a Pacific Northwestern totem, with curves and breasts that recall a stereotypically female form. To her immediate right is a sprite-like creature, aglow in orange and white. Her rounded face comes to a point at her chin. Her hair shoots upwards like vines. The variety of the women’s forms–both representational, with and iconic–enable the viewer to project themselves onto the woman. The diversity of forms gives the viewer space to see themselves represented in the global fight for justice for women.

“Many of us want a better world but we don’t even know if it’s possible,” Suarez said. “We’re together in making that happen.”

She added that she brings those lessons with her to her work in New Haven, and across the state. Shortly after she returned from Mexico, Covid-19 hit Connecticut, and Suarez’ work focused on prison abolition, continued mistreatment of migrants by ICE and law enforcement officials, and the overlapping, intersecting struggles for Black and Brown, immigrant, women’s, and LGBTQ+ justice and liberation. She is a founding member of New Haven's Semilla Collective, which pivoted to mutual aid in the wake of the pandemic.

In July 2020, she began organizing around the disappearance and murder of Lizzbeth Aleman-Popoca, a Mexican migrant woman and mother whose common-law husband was not arrested and charged until December of that year. She said that she still physically hurts when she learns about another woman who has been murdered or disappeared—including many in her home state.

This year, that has included Bridgeport’s Lauren Smith-Fields and Brenda Rawls. Three years after first taking the photos, Suarez said that it was important to her to share them around International Women’s Day as a reminder that the work continues. In their dedication to multi-generational sisterhood, to the land, and to each other, the Zapatistas have shown her the possibility of a different world, she said.

“We need to be talking about this,” she said. “We really need to take this action. So many of us are quiet, and we really need to break that silence. So many of us are still struggling with respect. How do we treat other women with the respect that we want to be [treated with]? There were so many things that came out of the event, but really it [the question] was: What are we going to do?”

Suarez also runs the project @vivanlasautonomas on Instagram, where she will be sharing some of the images and testimonies going forward.