Co-Op High School | Music | Visual Arts | COVID-19 | teachers | Education

Melissa Sands, the art teacher at the school formerly known as Christopher Columbus Family Academy (CCFA), on a video lesson with retired CCFA teacher, Carmen Conyer interpreting. Screenshot courtesy of Sands.

The most recent assignment in Melissa Sands’ art class was to draw a self-portrait using Spanish and English words and images that best represented a student’s inner self. If it had been in person, students would have collaged magazine cutouts, added in layers of oil pastel, and gotten out paint and brushes. This year, some didn't even have access to paper.

Sands is a teacher at the Blatchley Avenue school formerly known as Christopher Columbus Family Academy (CCFA). For over 20 years, she’s been teaching visual art in New Haven. Across the city, she is now one of a handful of art teachers still adapting to an online classroom almost a year into the Covid-19 pandemic. Her newest challenge is teaching some students who have returned to the classroom for in-person learning while others remain online.

“I think, for me ... the biggest challenge in creating lessons is accessibility,” she said. “Whenever I come up with something I have to have five ways to produce the outcome, because you don't know what they have.”

Across the district, different arts educators are taking different approaches. New Haven first closed its public schools on March 13 of last year, in an effort to stem the spread of the novel coronavirus. After heated debates in August, schools remained closed for the first semester of the current academic year. As of last week, the city’s elementary school students were allowed to return to the classroom. Of 6,000 who were eligible, 3,000 returned. As of Monday, three schools had reported Covid-19 cases among staff.

Ellen Maust, supervisor of performing and visual arts for New Haven Public Schools, praised arts teachers as particularly innovative during this time. Because students may not have the materials necessary to make work, she said, teachers have had to get creative. She said that the circumstances have allowed art educators to return to the principles of creating art as opposed to the end results.

“The arts right now, especially performing arts, are not so end product based,” she said. “So often in the arts we do a lot of recreation but, now our kids are really doing more creation which is exciting to see.”

What students are able to create varies from school to school, as some schools were able to provide art kits to students at the beginning of the school year, and others were not due to a lack of materials or funding. At Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School, for instance, teachers were able to provide materials for their students to pick up. Across town in Fair Haven, Sands was not able to send supplies to her students.

“If we had passed out our supplies, we wouldn't have any left,” she said. “There’s nothing to send home. The materials I purchased have to last all year for 500 kids.”

At the moment, Sands is only able to provide students with paper that can be picked up at the front office. Aware of the lack of supplies, Maust said that the district hopes to distribute art supplies that the Yale Center for British Art is in the process of collecting.

Parents, Retired Teachers Pitch In

Storytelling is at the core of Sands’ teaching. As the sole art teacher at the Blatchley Ave school, she said has the luck of being able to track the growth of approximately 500 students. She teaches her youngest students about the different lines in art with singing and dancing. Each consecutive year, students will sing the same song again but start to add to it, drawing on their lived experiences.

“We start with a story, we start with a book, we connect it to something going on in our lives,” she said.

As a dual language school—95 percent of her students identify as Latinx—Sands’ lessons follow Shelter Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) guidelines. As part of SIOP, lessons have to also be taught in the student’s dominant language, often but not always Spanish, to promote English Proficiency outside of designated English Language Learner (ELL) courses.

Sands does not speak Spanish fluently, but she’s become proficient in communicating with students and parents in person. Prior to last March, students with more proficiency in English or Spanish would translate for one another and help each other with assignments.

When school went remote, she had to figure out how to retain those same relationships with asynchronous teaching, particularly when teaching students with lower English proficiency. The end result was a collaboration between the school’s social worker, Melba Ramos-Matthews, a retired CCFA teacher, Carmen Conyer, and herself.

Sands recorded herself demonstrating the lesson of the day, and sent a script of the lesson to Ramos. Ramos then removed Sands’ voice recording and dubbed the video with her own recording in Spanish. Conyer sometimes attended lessons to help with live interpreting.

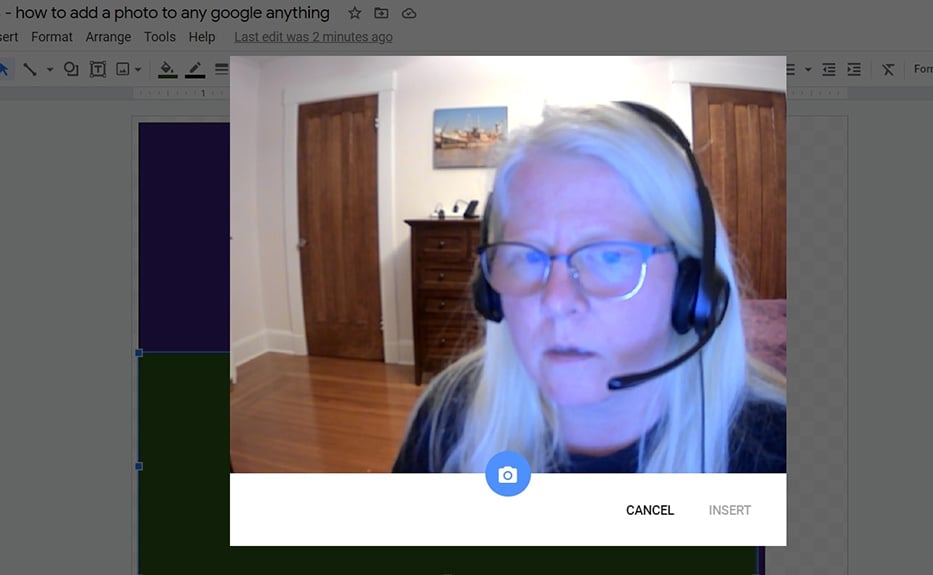

Sands shows students how to take a photo of themselves to insert into a Google Doc for a self-portrait. Screenshot courtesy of Melissa Sands.

Sands shows students how to take a photo of themselves to insert into a Google Doc for a self-portrait. Screenshot courtesy of Melissa Sands.

For one lesson, the dubbed version hadn’t been completed, leaving Sands with no translated Spanish content for the children. The class seemed like an uphill battle until one of the students’ mother stepped in and offered to translate.

“I didn’t even know the mom knew English because the student didn’t speak English,” she said. “She shared her screen, and walked everybody through it in Spanish. I swear she must have watched my video because she had my lingo down.”

Remote learning sometimes highlights students’ living conditions and shows up in their work, she said. For an assignment on perspective, students were supposed to draw their bedrooms but some students weren’t able to complete the assignment.

“You have students saying, ‘Miss Sands, I don’t have a bedroom,’ or 'I share my room with five other people,’” she said. “I learned early on that you have to really carefully word what you’re saying.”

Instead, the students designed their dream bedrooms. In another assignment asking for a self-portrait, some students completed their work using pen and notebook paper. Students with limited or no materials, took pictures of themselves using the camera on the school-issued Google Chromebooks. Then they digitally erased their faces before filling in the blank space with curved word art, clip art, and shapes all in Google Drawings. One student insisted on mailing the assignment to Sands because it was the only paper they had on hand.

“It’s not what’s on it [that matters],” she said. “It’s how much time you spent on it, what you put into it, and did you tell a story with it?”

A Cheerleader In The Sculpture Studio

Christopher Cozzi's classroom at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School (Co-Op) should be filled with massive and intricate sculptures and ceramics this time of year. Normally, his seniors are working on their capstone projects. In that universe, classical music plays in the background and everyone—including himself—can work steadily for 90 minutes with very little talking.

This year, the classroom is empty. Cozzi said he does not think there will be many senior capstone projects if school remains remote. From dozens of students across all grade levels, he said only one student is sculpting at home.

The school considered sending out specialized materials like clay and sculpting, but ultimately deemed that it wouldn’t be feasible, said Cozzi. The school still provides basic drawing art supplies if the students ask for it.

At school, Cozzi said he’s known for having a strong personality and pushing students on their work. If a student doesn’t like their work and tries to abandon it, he pushes them to complete it. Likewise, students see him struggle and fail in his own work as he works alongside them.

“I don't care that you don't like this, take you through, and we go through to where I feel that you're finished,” he said. “Who cares if you screwed up … you learn by failing. So, in the studio I push, push, push in a positive way.”

At the beginning of the fall semester, he tried to retain the same teaching philosophy with the incoming freshman class. It didn’t go well, he said. The students shut down. They did not respond to the approach and engaged very little.

Christopher Cozzi, ceramics and sculpture teacher, meets with a student in-person. Picture courtesy of Cozzi.

Christopher Cozzi, ceramics and sculpture teacher, meets with a student in-person. Picture courtesy of Cozzi.

He’s now a self-described cheerleader who tries to find something positive in each of the student’s works.

“I pivoted on a dime so I shifted to this very gentle and positive approach,” he said. “I'm not that anyway but … it's just a whole different level.”

As a result, most of the freshman students show up for class with a few no-shows. The older students have already worked with him in previous years and are consistent in attending class. In addition to regular class, Cozzi meets with each student for five minutes a week for one-on-one check-ins both to talk about their work and personal lives.

It’s no substitute for in-person class, he said. Students are currently working on two-dimensional drawings of sculptures or drawing designs either with pen and paper or in photoshop.

“I can feel they're struggling. I just try to be as empathetic as possible,” he said. “Come on, you gotta, gotta pick this up, you've got to do more here.”

Surprisingly, he said, many of the students don’t like to draw. In response, Cozzi emphasizes the importance of working through the process and finding that great idea.

“Some great architects, Mies van der Rohe. You look at his drawings. It's like chicken scratch,” he said. “But it's not the drawing, it's the idea and concept behind it.”

Penjunction In A Pandemic

Englart in April 2019, outside her classroom at Co-Op. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

In Mindi Englart’s creative writing class, students are still writing. Maybe a little less and slower than usual—but they’re still writing. Overall, classes are good, she said.

Surprisingly, few students have written about the pandemic directly since the start of the school year. Instead, they are writing about gender, Black Lives Matter, immigration, and other social issues close to them. Many students are writing about mental health, as it affects their work and lives.

“I think their issues are magnified for them,” she said. “They’re clearly all consumed by the pandemic … but maybe they just want to be doing other stuff, you know, while they can with other people in a class.”

Englart, who teaches English and creative writing at Co-Op, was able to transfer most of her in-person teaching model to remote teaching with some minor adjustments. She had already been using Google Docs for many years and her classroom model, based on a publishing house, translated easily to Zoom’s breakout rooms.

As part of the publishing house, students submit a job application and interview for the job they select. As part of their job, students can choose to write for the school’s newspaper Co-op Voices, the literary magazine Metamorphosis, write personal essays, coauthor a book, or even do an entire class anthology.

“We go into [Zoom] breakout rooms, so I'll leave the big group working, or sometimes we'll have a few breakout rooms with different people who are working on different projects together,” she said. “I'll go into a room alone with one person and just edit their work directly with them … just like how it would be in regular school.”

She was able to retain a defining ritual of her classroom called "penjunction." A term coined by a former student, it is the junction of the pen, a weekly workshop where students can share their work to the class with their own set of instructions. They might want guided feedback, brainstorm some ideas, or experiment with something new.

“I wouldn't get in someone's way ... or of what they're trying to push themselves in terms of their writing and their creativity,” she said. “It's not so important to me that they learn particular things from me.”

At minimum, students have to submit one piece of writing a week. Englart encourages them to submit more. Some weeks, students barely fill the page, and others they submit 10 pages of research and writing she said. Equally as important as the writing is the relationships she continues to have with the students.

“I mean it's also always been really important to factor in what a real person's real life is like,” she said. “You know, teachers and school in the best of all worlds help fill in the gaps. It's a great equalizer supposedly, and I feel that that's part of my job is to help equalize people and what they're missing to bring in, and that's why you have to tailor you can't just give everyone the same thing.”

The Band Plays On—And Composes

NHPS instructors Natalie Jimenez-Lara and Jose Lara at ARTE's Saturday academy in October 2019. Lucy Gellman pre-pandemic file photo.

In Fair Haven—at least, through a screen—teacher and trombonist Jose Lara has set out to recreate as much as he can about in-person band class in the virtual realm. Band isn’t just about the music, he said—it's about the jokes within sections, the ritual of shining your instruments, and learning to replace broken reeds in person.

“My goal really hasn’t changed,” he said. “At the end of the day I want my kids to enjoy creating music and appreciate it more than what they started with.”

As the instrumental music teacher at John S. Martinez Sea and Sky STEM Magnet School, many students get to hold their very first personal instrument by the time they enter middle school under his supervision.

Getting instruments to newcomers has proved to be a challenge across the district, said Maust. Teaching students about their instruments requires physical touch. Usually, teachers show students how to hold their new instruments, move their bodies, and adjust their posture.

At the beginning of the fall semester, many band educators across the district held off on distributing physical instruments, buoyed by the possibility of returning to in-person classes in November. They opted to do reviews and supplemental learning until the students returned she said.

But that gamble backfired when the district announced the decision to continue remote learning through the remainder of 2020, and then flipped again to a hybrid model this month.

After the initial delay, approximately 85 percent of students at the school have instruments at home said Lara. Maust said the majority of schools across the district have their kids on instruments. Schools hosted instruments drives during the day for parents and guardians to pick up instruments.

For the roughly 15 percent of students who do not yet have instruments at home, instruments are available at the school if they choose to pick them up. Lara believes that those parents have not picked up the instruments due to time conflicts or a lack of transportation to the school.

“All the schools are handing out technology,” he said. “It is only fair that we give out instruments as school supplies.”

The cost of renting an instrument for the year is $30 to $40. Some students opt to buy their own personal instruments, often from Amazon. Sometimes, Lara said he would eat the cost of renting the instrument on behalf of a student. But with pandemic’s economic toll, he’s been able to do so less.

So far, he said that maintenance has been the biggest issue with instruments at home. In person, he was able to teach students how to do repairs themselves. Now, he said, students are more fearful of breaking their instruments. Students have the option to drop off their instruments at the school and he will repair. So far, he’s completed more than 10 repairs and expects more as the instruments wear down.

In his classroom, there has been a strong emphasis on both playing and composing music for all students. As Lara pointed out, having an instrument doesn’t necessarily mean a student can play it.

“It is hard to get students to play their instruments when their parents or young siblings are asleep,” he said. “Maybe they just can’t make loud noises for the neighbors.”

To include students as much as possible, Lara often has his classes compose and record music in online software like Bandlab and Soundtrap. The latter has better integration with Google Classroom, making it easier for students to use. While Lara was using both prior to the pandemic, he said that the need to have more modern music instruction has become clear.

“We’re in the modern era,” he said. “Lemme show you how to use this software to make a beat. They’ll approach modern music with some more depth and be certain about what they want to learn.”

Some days have been more difficult than others. He spoke about coming to class and noticing students were dejected just by the way they greeted him. On occasion, he has set aside time in class to speak with the students about their emotions both as a class and privately.

“Sometimes, we just have a fun talk,” he said. “What movie did you watch? We’ll just talk for a few minutes and bring it back to discussing what we had paused.”

For him, art education and exposure to art at large remains a necessity during a time when students are struggling with mental health and isolation.

“How many times has the arts help a nation heal? The arts help express a movement? The arts help convey a message,” he said. “You’re not a robot or a machine. Everybody enjoys it as a profession or a hobby.”