Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School | Dance | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | The Hill | COVID-19

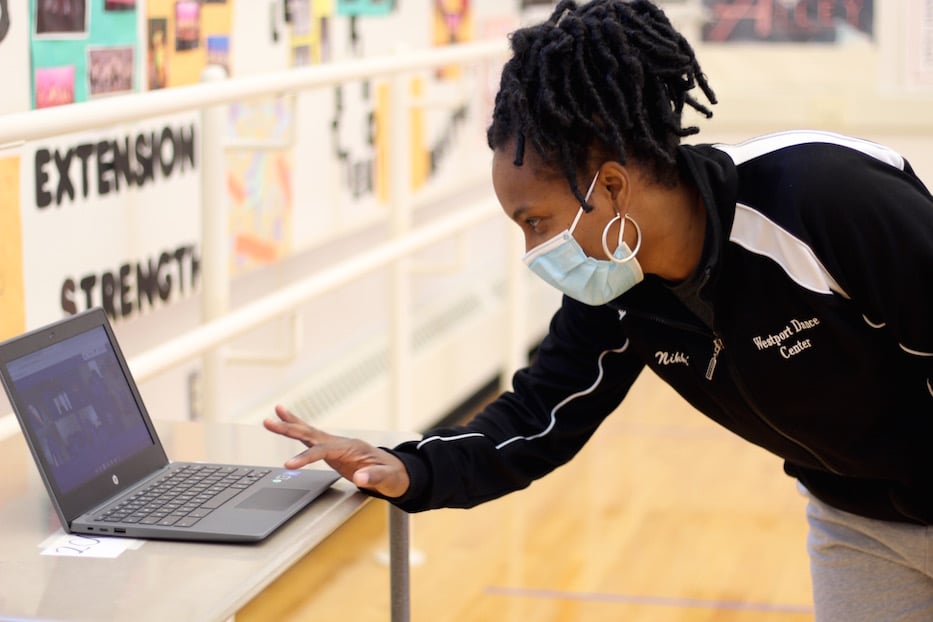

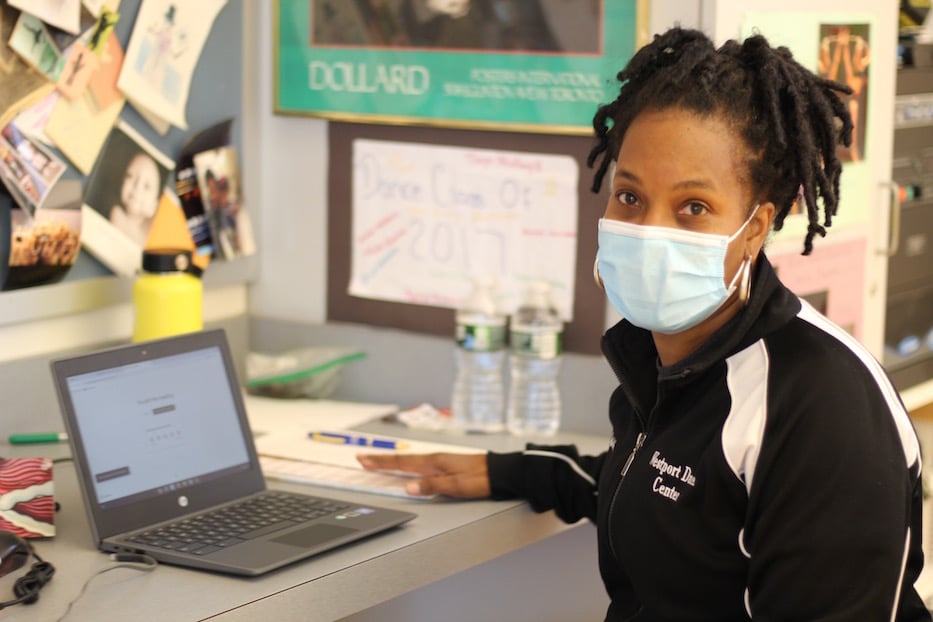

| Nikki Claxton. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Nikki Claxton looked into the screen, one finger pointed as her feet flexed below. A drumbeat threaded itself into every movement. In 10 gridded boxes, legs stretched in time with the music. Necks rolled back and forth; chins pressed slowly to chests. Claxton adjusted her newest accessory, a seafoam-blue medical mask.

Claxton is one of the arts instructors at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School (BRAMS), a large brick building that rises off Kimberly Avenue in the city’s Hill neighborhood. Three days a week, she leaves her home to come into the school to teach from a laptop in her dance studio. As students navigate remote learning for the first 10 weeks of the school year, she is working on it from a classroom that is quieter than it has been in years.

“Attendance has been great,” she said on a recent Tuesday, in the seven-minute break she gets between classes. “There’s nothing like in-person learning. But students have really kept up, and they’re showing up. And that feels great.”

That morning, Claxton was with her eighth graders, warming them up before introducing new choreography. Five weeks into the school year, she has a rhythm to her classes: she takes attendance at her desk, and then props the computer up at the back of her studio, on an elevated cart that lets students see her as she walks them through steps. Tuesday, eight eager faces stared at Claxton. Two more students kept their cameras off. All of them are expected to show up to class in uniform, a black leotard and tights.

On her end of the screen, the studio looks almost as it always has, but without any young people in it. Black and red letters arrange themselves into dance terminology and genres. A huge poster for Alvin Ailey blinks out nearby. On their ends, rooms shift in and out of focus behind them, turned into temporary dance studios.

From a speaker, Claxton summoned a drumbeat with jingling strings, the sound coasting over the floors. Strains of pop music hummed through the wall from Hannah Healy’s virtual dance class next door. Claxton slid into place before the computer and began guiding students through neck and shoulder rolls.

“Just do the best you can,” she said. Her eyes crinkled in the corners, the new shorthand for a smile. She clapped to keep the rhythm. “Here we go. One. Two. Three. Four.”

The beat quickened. Someone spoke in a murmur over the track. Claxton brought her arms up in time with the music, a signal that it was time for jumping jacks. On screen, arms flew out to the side. Legs straightened and cut through the air. Fingers spread out from hands one by one. Claxton leaned in, scrutinizing straight backs and bending knees.

“Put those feet together Martina!” she said, never quite raising her voice to a yell. In the corner, a clock struck 10:20 a.m. She gave students a few minutes for a water break. When they returned, she guided them onto their backs.

“Breathe! Breathe! Breathe!” she cried at the screen, backing up to watch the stretches. “Make sure you’re breathing! Intentionally breathing!”

For both Claxton and her students, it feels better than the spring, when teachers were allowed to turn on their cameras but students were not. When schools closed in March, several of her students had just finished a performance for Black History Month and started in on new choreography. With classrooms empty and cameras suddenly off, the distance felt immense.

Now, at least she is able to see them—and they are able to see each other.

“I’m happy that we’re able to come together and all learn as a class,” said eighth grader Laila Kelly-Walker, piping up from Claxton’s computer screen. “It’s hard, but we can all kind of be here.”

“I feel like it helps me get my emotions out,” chimed in Anya Williams.

Dyani Dolberry said the chance to get up and move has become a stress reliever when she may need it most. Mari Arnold, who had been quiet for a few moments, nodded her head.

“I feel like it’s a nice little break because we’re in front of the computer all day,” she said. “It helps us forget what’s happening.”

Bridging The Digital Divide

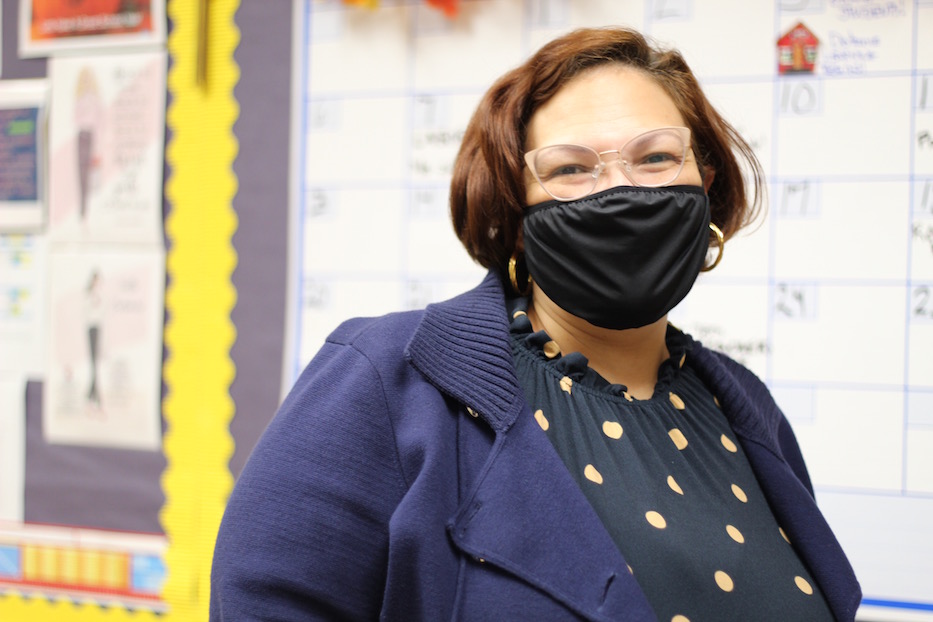

| Principal Jennifer Jenkins. |

In her office downstairs, Principal Jennifer Jenkins was working on an internet conundrum. Since the beginning of school, Jenkins has been trying to figure out how to provide more reliable WiFi connections to students who have picked up their laptops from the district, but have struggled to log into classes.

It’s a problem that she’s taking on as a parent, a new principal, and a lifelong New Havener. Jenkins grew up in New Haven and graduated from James Hillhouse High School. Prior to this year, she was the principal at Ross Woodward Classical Studies Magnet School. She’s also a mom: her daughter Jayla, who graduated from Betsy Ross last year, is a freshman at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School.

At the end of August, the New Haven Board of Education voted to keep classes online for the first 10 weeks of the school year. One week in, they amended that slightly, allowing a few schools to reopen for a very small number of students with learning disabilities. Otherwise, classes have remained online. Most teachers are using Google Meet; some students have said they also have classes on Zoom.

The district has also committed to distributing 3,000 hotspot devices and extending internet access at 13 schools. Each school is supposed to have a two-and-a-half-block WiFi radius; Betsy Ross is one of them. In early September, Schools Superintendent Iline Tracey announced that 2,500 students across the district had not yet logged in for classes, and 18,000 had.

| Assistant Principal Tiffany Rauch. |

Some students at Betsy Ross, of which there are currently 406, are still scrambling to get into their classes. Even if they do, a school-based hotspot only goes so far: classes and late-night homework can’t be done in a parking lot if they’re out of the radius. There are students who live outside of hotspot zones or in other towns. On social media, several parents have also reported that the school-supplied chromebooks shut down as soon as they are unplugged from a power source.

“It’s a very different time for technology and access,” Jenkins said. “Most of the students picked up their chromebooks, so that tells us that they don’t have access to the internet. We’re trying to make sure everyone has access.”

Students are not the only ones to have struggled with the new technology. Assistant Principal Tiffany Rauch, who is also new this year, said that teaching online has also been an undertaking for some of the school’s teachers, who were “at all different levels” at the beginning of the year.

Prior to 2020, Betsy Ross wasn’t a Google School, meaning that all of the technology is new to faculty. For as many teachers who have gotten the hang of Google Classroom, there are others who struggle with having their students on a screen.

“I like to work with the students and staff, so this feels different,” she said. “I’m very personal. I like to make those connections.”

“We Try To Stay As Positive As Possible”

| Sylvia Petriccione: “The arts are going to thrive. They’ve got to. We cannot let this drop for our students." |

Five weeks into the school year, Betsy Ross is also accepting new students. BRAMS is a magnet school, meaning that several of its students live in the suburbs and surrounding towns. When New Haven announced plans to go fully remote—the only city in the state to do so—several parents placed their kids in district schools that were hybrid or in person. A few spots opened up on BRAMS’ waitlist.

This year, 35 students have withdrawn, not including new students who accepted and then declined due to remote learning. The school has welcomed approximately 35 new sixth graders, 18 new seventh graders, and one new eighth grader. The fifth grade class has 70 total students.

It has created a rushed, delicate ballet for Arts Coordinator Sylvia Petriccione, a 35-year veteran of the school system who is much more commonly known by students and parents alike as “Ms. Pet.” On a recent Tuesday, she prepared a new seventh grader for orientation over the phone, doing the mental gymnastics in what she would need to have ready for pickup. Then she visited students, popping in on classes. Her blue sweater billowed as she glided through the hallways.

“We try to stay as positive as possible, because we’re working with young people,” she said as she stepped out of the elevator that connects the floors. “The arts are going to thrive. They’ve got to. We cannot let this drop for our students—not on my watch. It’s what makes us tick. It really is the heart of the school.”

It may be the strangest fall that she’s had in 22 years at Betsy Ross. In a normal year, Petriccione guides fifth graders through an introduction to the arts, during which they rotate through the school’s four art forms (dance, drama, music, and visual arts) before choosing a concentration. Older students choose an art form, but also stay with general arts classes for the entirety of their middle school experience.

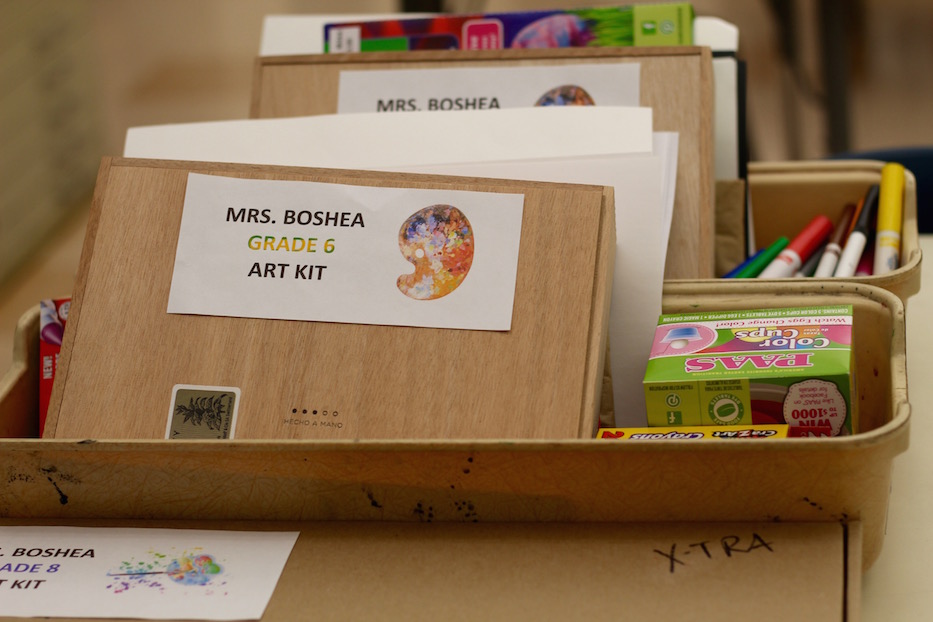

This year, fifth graders are doing all of that virtually. For sixth through eighth graders, the general art classes “have been a sacrifice” because of COVID-19, as Petriccione rearranges curricula to work for remote classes. At the beginning of the year, she worked with teachers to assemble to-go arts packets, with materials including choral and instrumental music and arts materials. She said the school is working to plan online concerts.

In the midst of it all, she said, she often thinks about how unnaturally quiet the school is. Announcements are infrequent on the loudspeaker. No students dart out from doorways and corners, running because they are late to class. In the hallways, it’s possible to hear a pin drop where there should be cacophonous laughter. She is often the only one making her way through them between class periods.

Because it is unclear whether students will return in November—Petriccione hopes so, she said—Betsy Ross is preparing its classrooms, hallways, bathrooms and offices for use on a hybrid schedule. Inside the main office, industrial-sized jugs of hand sanitizer sit with notes on how to pump judiciously. At the desk, a plexiglass barrier hangs between Irma Rodriguez and two seats for students or parents. A huge paper calendar is festooned with orange and red leaves, decorated as it always has been to announce the first signs of fall.

In the hallways, empty lockers are now accompanied by colored tape, marking lines on the floor where students are expected to stand apart from each other. Bathrooms have signs about hand washing and virus prevention. Bright arrows and large, shoe-sized circles show the intended flow of foot traffic.

In drama and music classrooms, 12 straight-backed chairs sit empty, spaced six feet apart. In dance studios, blue and pink tape has created a grid for students. Art teachers have devised learning stations. They are still figuring out the computer setup, on which students do graphic art.

For now, only a few teachers filter in and out of those classrooms. Earlier this month, administrators at the school realized that only a certain number of faculty could teach on-site at one time: if there were too many, some lost WiFi. Petriccione makes it her business to check in on classes, taking the trip from the first to the second floor several times each day.

“Hi dancers!” she waved into the laptop in Claxton’s classroom early in the lesson, giving a double thumbs-up. “We getting some water? Are we getting conditioned today?”

“I miss you!,” she added with a final wave.

“It’s For Everyone”

| Theater teacher Daniel Sarnelli. |

Around the school, teachers are adjusting. On the first floor on a recent Tuesday, theater teacher Daniel Sarnelli leaned into a screen, an electric blue gaiter pulled up over his mouth and nose. On the other side of the screen, his eighth graders were practicing poetry recitations for Black History Month.

Sarnelli has asked students to practice by recording themselves, listening back, and then reading for the class. Tuesday, one student read out Georgia Douglas Johnson’s “When I Rise Up.” When she stopped on the word “tranquil,” the class took a beat to discuss the term.

Back in her classroom, Claxton turned to Alicia Keys’ “Good Job” for the second time in the 70-minute class. After conditioning from their bedrooms, kitchens, and living rooms, students were ready to begin choreographing a new piece. Claxton mapped out the movements as she tried them, her body bending forward with the lyrics. Neither Claxton nor school administrators know whether or when students will be able to perform it together.

You’re the engine that makes all things go

And you’re always in disguise, my hero

I see your light in the dark

Smile in my face when we all know it's hard

She turned to the laptop and then to the front of the classroom, where an entire wall is covered with a mirror. With the first notes of piano, she made a slowed-down running motion, her arms punching the air. Suddenly, she explained to students, she was the engine. When they did the movement, they would be too.

In the past months, the song has become an anthem for first responders, essential workers, teachers, and parents. Claxton said she chose the song because it felt applicable to everyone—to her, to her students, and to the other kids and parents making it through remote school. Her son is a sixth grader at Betsy Ross, studying visual arts.

“It says ‘good job’ to everyone that’s been in this,” she said. “It’s for everyone. Good job that you’re doing this work. Good job that you’re making it through.”