Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | COVID-19

| Kaatje Welsh. Michelle Welsh Photo. All of the students in the article are young writers, and alumni of the Arts Paper's Youth Arts Journalism Program. |

Kaatje Welsh was sailing through her first day of junior year. Or trying to.

She pulled herself out of bed early. She found a cheery homeroom waiting for her—even through a screen. She navigated prep for Catcher In The Rye and jumped into the first chapter of AP Biology. She wrapped her mind around new 30-minute breaks between classes.

Then she got to Spanish class, and a bunch of her classmates couldn’t log onto the system. It made her start thinking about every other tech glitch she’d seen during the day.

Welsh, a junior at New Haven Academy (NHA), is one of the almost 21,000 New Haven Public Schools students starting the school year virtually this month. Like many of her peers, she spent Thursday and Friday in front of a laptop for hours, trying to stay focused as she introduced herself to new classmates and teachers. The Board of Education has not yet released numbers on attendance.

In late August, the city’s Board of Education voted to keep learning fully remote for the first 10 weeks of the year, a measure meant to stem the spread of COVID-19. New Haven is currently the only district in the state that is not following an in-person or hybrid teaching model. During the summer, both teachers and parents spoke out forcefully against in-person teaching, including during a series of actions in Hartford last month.

They argued that New Haven schools do not have the adequate resources to prepare safe and COVID-19 compliant classrooms, or provide trauma-informed counseling for students experiencing loss related to the pandemic and its rolling aftershocks. Proponents of in-person and hybrid schooling have argued that COVID-19 rates are low enough in the state to go back safely, and that the educational benefits outweigh the risks. Risks include COVID-19 infecting and even killing students, teachers, and family members, particularly in multigenerational households.

As the year began Thursday and Friday, some students tried to go into it with an open mind. Welsh, who lives in Branford but attends NHA, said that getting up on time was initially a struggle. When she did, she found a day that was “a little hectic,” but more engaging and cohesive than her classes were from March through June.

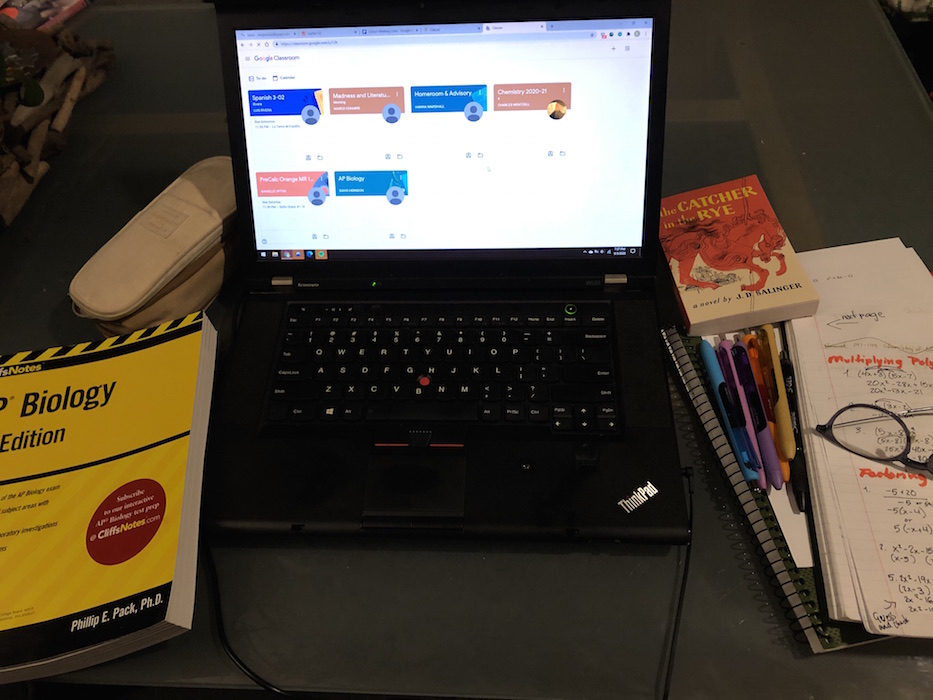

Welsh has a remote learning station set up in her kitchen, where she can work on her laptop at a long table. The commute is much shorter: she can roll out of bed and be in her homeroom in five minutes or less (after a summer of sleeping in, she said those early start times are still hard). Everything’s within reach, so she can switch out a FAFSA form for her college prep seminar to a not-yet-annotated copy of Catcher In The Rye, which she’s starting for English III.

| Welsh's setup in her kitchen. Kaatje Welsh Photo. |

Around her, a series of small, unexpected distractions have replaced cacophonous classrooms and lunch periods with close to 100 students. Before COVID-19, Welsh was used to classes full of her peers, where laughter in the hallways, quick catch-ups with friends, and the rhythm of a volleyed question-and-answer were commonplace.

Now, voices come through a tiny port on her computer, sometimes tinny, delayed and distorted. She works close to the washing machine, which beeps, buzzes and thumps as clothes soak and spin inside of it. Her older sister Malenky is still home from The Juilliard School, where classes are still remote. On the first day of school, she said the two did their best to stay out of each other’s way.

This fall, New Haven Academy has let teachers decide whether they are using Google Meet or Zoom, a system that had Welsh toggling between the two with 30-minute breaks in between. In her junior year homeroom, she saw faces of classmates that she’d been missing since mid-March. It was warm and friendly, she said—but nothing like the school she is used to. With live teaching in full swing, her teachers have asked her to turn her camera on, some using it as a metric for attendance.

“There were a bunch of little technical difficulties,” she said. “Kids couldn’t hear. Sometimes people couldn’t get into the Zoom. There was a lot of ‘get to know you,’ first day kind of activities, which I’m not the biggest fan of.”

This fall, she’s taking eight classes, including a seminar that helps with college applications, FAFSA and scholarship forms, and college essay prep. Her goal is staying on top of her work, a course load that includes two science classes, English and Philosophy, U.S. History, Spanish, and precalculus.

Since COVID-19 closed the school building in March, she’s worked on new time management skills and doubled down on staying on top of work before it piles up. In the spring, she said, the distance learning model meant that she let assignments languish until the last minute. With live remote teaching, she feels like she has to be more responsive. She doesn’t like turning her camera on, but said it helps her stay focused instead of letting her attention wander.

Welsh added that she was expecting junior year to be hard—she takes the SAT in a few months—but never imagined it would be virtual. She also thinks remote teaching is safer than in-person, despite missing her classmates.

“I don’t trust that my peers are going to wear masks and stay six feet apart,” she said. “NHA is a relatively small school. Lunch waves are like, 100 kids, all in a small little lunchroom. There would be no way to keep students six feet away from each other. I’d rather be at my own house, where I can control those things around me.”

| Maxwell Gamboa, who usually jut goes by Max. Max Gamboa Photo. |

Metropolitan Business Academy junior Maxwell Gamboa was so excited for his 8:30 a.m. school day that he woke up two hours before it started. Gamboa grew up in New Haven but lives in North Haven with his grandparents. Getting to school used to require alarms, rushed mornings, rides from his grandfather, or a school bus commute at 6:50 a.m. Now, his classroom is a desk in the corner of his bedroom. He has two friendly learning companions: a friendly Brazilian shorthair cat named Ruby and his 1-year-old tortoise, Akiko.

Gamboa suggested that he’s a rarity: he likes remote learning, even though he knows many of his classmates do not. The model works for him because of the anxiety he used to experience in school, particularly in larger classes. When Gamboa was in the physical classroom, he struggled to jump into a group discussion or answer questions in front of his classmates. Over Google Meet on Thursday, he discovered that he didn’t have the same problem. If a teacher asked a question, he often jumped in with an answer.

“I’m trying to be more confident this year in myself,” he said. “I feel like that will help with online. On a [Google Meet] call, there’s less anxiety for me. If we’re on a call, and it’s quiet, I’m just going to answer. Personally, as someone who was already kind of isolated at school, going online didn’t really impact me that much.”

He’s taking a full course load, including Spanish, English III, civics, chemistry, algebra II, business law, health and constitutional law. When he arrived at the school to pick up a laptop last week, his constitutional law teacher was there giving out miniature, hand-sized copies of the constitution that the class will be referencing this semester.

Two days in, the system is working for him. On the first day of civics, the class looked at John Trumbull’s The Declaration Of Independence, which lives in the collection of the nearby Yale University Art Gallery. In the painting, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston and Roger Sherman present the Declaration to John Hancock as all 56 delegates look on. Everyone in the painting is white and male.

| Max Gamboa Photo. |

Gamboa said he isn’t crazy about the painting, which shows the makings of a country built on the ideals of a small, self-selecting group of white, male land owners. But the class also looked at a much more recent image that Ancestry.com and Droga5 worked on in 2017, where subjects are replaced with their descendants in period dress. In the photograph, viewers get a kaleidoscopic view of America that the original signatories could not have imagined and may not have intended, including women practicing law and a Black reverend who is the great-grandchild of Thomas Jefferson.

“We talked about American ideals and what America was built on,” Gamboa said. “As a person in the LGBT community and the son of an immigrant, that really spoke to me.”

As the year gets underway, he’s also trying to find ways to support his peers. As a leader of the school’s Gender-Sexuality Alliance (GSA), he is already working to set up an emergency hotline for LGBTQ+ students who may be closeted or barred from attending virtual meetings by family members or guardians. He said he worries for classmates who are struggling with social isolation and unsafe home situations.

“I send my support to students who are having a hard time with this,” he said.

Henry Fernandez, a sophomore at Engineering and Science University Magnet School (ESUMS), had a different take. When asked how his first day of school had gone on Thursday, he took a deep breath in.

“It was,” he said. “It was and it wasn’t.”

Fernandez, who lives in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood, explained that for the first half of the day, everything had been fine. This year, he’s taking AP government, honors chemistry, algebra II, English II, principles of engineering, and band on a rotating schedule. Thursday, teachers seemed like they were getting the hang of Google Meet. Students showed up. He was too busy to think about his first band class Friday, in which he needed to figure out drum practice without a drum kit.

Then halfway through the day—in total, some six hours spent in front of a screen—“it just began to fall apart.” Teachers struggled with timing lessons that fit correctly into periods that were technically live, but still remote. It was harder to learn things on a computer that had seemed intuitive in the school’s “Clabs,” hybrid classroom-laboratories that are designed for live experiments and have newer computers and up-to-date software. Ten minutes into the final class of the day, a teacher’s WiFi stopped working.

“They sort of freaked out,” he recalled. After failed attempts to get back online, class was dismissed early.

But, he added, he thinks there are benefits to online learning—not getting COVID-19 principal among them. Before schools closed their physical doors in March, Fernandez woke up at 5:50 a.m. to make it to school for a 7:30 a.m. start. Now, he gets up at 7 a.m. The extra 70 minutes of sleep means he feels sharper when he sits down for classes. He likes that he uses less paper and praised the school for making sure students had “these really nice computers” to learn.

He added that he’d be more upset if he were a freshman, junior or senior. To him, sophomore year feels neutral.

“I’m in the intermediary year of high school,” he said. “It’s basically the second year of freshman year. It’s a year that's very much like, you’re in the middle of everything. You’re getting older, but you’re not old yet. You’re just kind of coasting for another year.”

He also thinks it’s safer than meeting in-person. Over the summer, Fernandez volunteered with Read To Grow, helping with its outdoor book distribution. For weeks, he heard from parents who were terrified of the risk of COVID-19 infection for themselves, their children, and the other people who lived in their homes.

“It was definitely a rocky start to the year,” he said. “But I like it. I think it’s necessary, and I think there’s much worse alternatives. I think it would have been worse if we had stayed in-person and someone had gotten sick. Or like, if a teacher died. Or like, what is a kid with asthma supposed to do?”

An Unexpected Senior Year

| Green last year at the New Haven Free Public Library. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School senior Jamiah Green spent the spring feeling stressed about remote learning. First, she had to get through online classes. Then she picked up a job and learned a new way of communicating with her friends (she also continued freelancing for this publication). Now that she’s navigated all of those—and live teaching has returned—she’s balancing a full class load, college applications, and a job that starts when classes end.

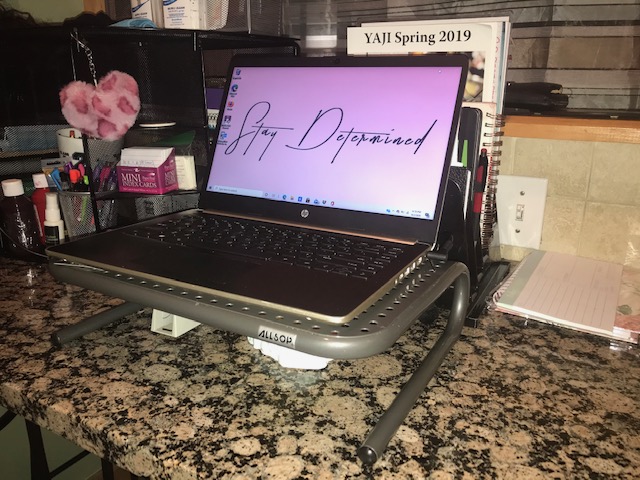

Her day begins well before 7:30 a.m., first period at Co-Op. Last September, that meant getting from West Haven to downtown New Haven before the first period. This year, her commute is just a few rooms from her bedroom to the kitchen, where her computer sits on an elevated platform with her books stacked neatly behind it. From her screen, a message that reads “Stay Determined” glows in delicate script against a pink background.

While she had hoped to be back in the building by the fall, she’s trying to stay focused on classes and college applications. An aspiring lawyer, Green is planning to apply to Southern Connecticut State University, the University of Connecticut, and Albertus Magnus. She doesn’t like not being busy, she said: she filled her only free period with a class on criminal pathology at Gateway Community College.

Her other classes amount to roughly six hours a day on a screen. When classes end Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, she gets in her car and heads to a food service job that she also works at on the weekends.

“My main thing is college,” she said. “I just try to stay ahead and give myself career opportunities.”

While she believes that remote learning is the safest option, she added, she doesn’t have to be happy about it. When the district announced its closure in mid-March, Green thought she would be doing remote learning for a week, maybe two at the most. She and her friends tried to stay upbeat as they moved things to text messages, FaceTime and Instagram. They joked about how absurd online graduations and prom through a screen might look.

Then a week became a month, which became three months, which became the fall of her senior year.

| Jamiah Green Photo. |

“I’m actually looking forward to everything being online,, because I feel like if it’s planned around an online resource, then we have a better chance of knowing what we have to do and how to focus on everything,” she said. “It kind of also sucks, because I do miss the in-person teaching.”

“For me, I function better that way,” she continued. “When I know what I’m doing, when I’m right there in front of everything, I can finish the work by the end of the day. Online, it’s draining. You’re staring at your screen all day. But I’d rather be safe than do something that’s better just for me.”

She’s also one of many New Haven students balancing a new job on top of school. Over the summer, she picked up a part-time job at Arby’s that still has her working shifts five days a week. Because she shares a home with her grandmother, she still keeps most social interactions with friends to a minimum, using technology over socially distanced gatherings. She’s been to the mall once, to celebrate a friend’s birthday. She said once was enough.

At home, her “pod” is small: just her grandmother, cousin, and aunt. Because all of them have jobs that put them in contact with other people, they have ground rules that include applying hand sanitizer by the front door, as soon as they’ve gotten home from work. Her grandmother carries extra masks and gloves in her car. Green said she tries to think about it in terms of the 1918 flu pandemic—that there is so much they don’t know, so they are trying to play by the virus’ rules and hope for the best.

“I still do worry,” she said. “You just never know what could happen. I could go to work and be handling customers’ money. Come home, start touching stuff, and next thing you know the virus is here. But I don’t try to worry too much about it. Eventually, this pandemic is going to die down … I just try to live the best life that I can through the pandemic and hope that everything turns out fine.”

She’s also trying to prepare herself for what the year might look like if students don’t go back after the first 10 weeks of remote learning, or if they go back and then schools shut down again. Last year, Green planned to play volleyball with the team at James Hillhouse High School. Now, she and her friends are bracing for the possibility of online prom and socially distanced graduations.

“My hopes for this year are pretty much just to stay safe,” she said. “When I first heard we were going back to school, I was kind of nervous. I’d heard about UConn students who went back and were testing positive for the coronavirus. I was like: If they’re testing positive and they’re college students, what’s going to happen to us as high school students? And to middle school kids? I understand how everyone was saying they can’t function online, but I think it is safer this way.”

| Nadia Gaskins at Co-Op in fall 2018. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

Her best friend, Nadia “Navi” Gaskins, noted that it isn’t shaping up to be the year she expected either. When New Haven schools went remote in March, Gaskins thought the response to COVID-19 was overblown. She went so far as to blast early COVID-19 reporting, shutdowns, and precautions in an episode of her podcast.

Then she watched as the virus infected and killed Black Americans at a rate far higher than their white counterparts. As a member of The Perfect Blend’s youth leadership team, she spent the spring and summer months talking about the layered traumas of COVID-19, structural racism, and gun violence in New Haven.

While she struggled with distance learning in the spring, she said she’s ready for remote school as it begins this year. She’s been working to eliminate distractions including her cell phone and the television, which she turns off for the duration of the school day.

“I’m really excited about live teaching, knowing I’ll be able to interact with my teacher on a personal level,” she said. “I’m excited—I’m ecstatic— that it’s my senior year. Everything’s so surreal. It’s like, high school went by so fast.”

“College feels really heavy right now,” she later added. “I’m working on just getting good grades, just staying on top of everything because I want to get into a good school.”

When she started senior year last week, she tried to focus on college, which seems “way more real now” that applications are due in just a few months. She’s aiming for Stanford University, a school that she’s dreamed about since she was a little kid. Also on her list are Vanderbilt, Elms College, and several HBCUs.

“Of course I’m concerned about the fact that I don’t know if I will be able to have our prom or our graduation,” she said. “The class of 2020 did have both, but not in the same way. I’m hoping that the rate of infection stays low, and our senior activities are going to go as planned.”

“My friends—we’re doing a lot of video calling, trying to make sure that we’re all doing okay during this time,” she added. “Trauma on top of trauma is not a good mix.”