Photography | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Ninth Square | Visual Arts

| Detail from Monique Atherton's Everyday Encounters Series (Basie Walk Sequence). |

At first it’s just a guy walking down Chapel Street. White dress shirt unbuttoned, sleeves rolled up, shades on. Something hangs heavy from his right hand. He has a swagger like he owns the whole Ninth Square, and that’s not specifically a good thing. The blocks roll by, chopped up to show the journey from front and back. There’s 900 Chapel St., an empty lot at the corner of Chapel and Orange, Elm City Market just beyond it. His reflection undulates softly in the windows.

But does he know he’s being watched? Is he playing the photographer? Is she playing him? Do they know each other? Is the viewer actually the odd one out?

Monique Atherton’s “Everyday Encounters Series (Basie Walk Sequence)” sets a sort of curious, propulsive and shifting tone for Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography, running at Artspace New Haven through Sept. 14. As Atherton’s images wrap the space, other works inside address, explore, and push back against the long history of photography. Or as curators have deemed it, “the event of photography.”

“The exhibition refutes the notion of the photographer as a lone actor who determines the meaning of a photographic encounter for others, and seeks to make visible the various relationships, exchanges, and interactions between the participants in the event of photography that result in tangible traces of collaboration,” reads an introductory text.

It rings true to the way the history of photography is still widely taught: photographer identifies subject, photographer frames and captures subject, subject lives forever frozen in that moment, photographer is lauded for the image. The subject doesn’t always have a name while the photographer becomes a known and often celebrated quantity. Even the well-intentioned viewer takes it at face value, and the cycle repeats itself.

| Installation detail of Rachelle Mozman Solano's Soledad y Natasha por el Castillo. Beside it, out of focus, is her She had a terrible reputation of having brought a number of her lovers to their grave (2018). |

It’s a history in which private moments are often made public for a photographer’s gain, with or without a subject’s consent. Consider, for instance, Alexander Gardner hauling the corpse of a young soldier across the smoking battlegrounds of the Civil War for his iconic image, “Home Of A Rebel Sharpshooter.” Or Jacob Riis, long heralded for documenting American poverty, using early flashbulb photography to make the grim, exhausted squalor of early twentieth century New York look even more grim and exhausted. That’s right, the curators seem to tell viewers warily—photography is not exempt from exploitation, and it never was.

Instead, it's become a convention that has held through civil conflicts and global warfare, documented manmade epidemics and medicalized ones too, witnessed and in some circumstances enabled race-based hatred, bigotry, colonialism, and the spread of propaganda. These images are preserved, reproduced and replicated under the guise of knowledge and public benefit; they become templates for more photographs like them. In other words, the optics of justice (or lack thereof) become more visible than justice itself. The big, growing archive that is the overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly male history of photography lives on.

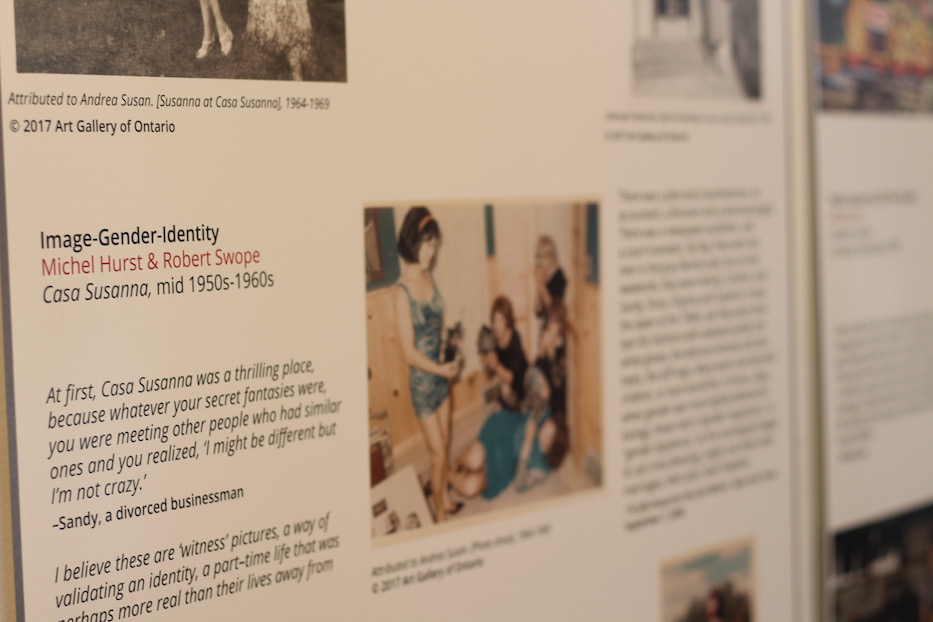

On Artspace’s walls, curators and artists pull back the curtain one image at a time, fusing their own commentary and work with that of New Haven photographers Monique Atherton, Thomas Breen, Ed Gendron, Daniel Eugene, Rachelle Mozman Solano, Thana Faroq, and various collaborators that each of them have worked with. A portion of the show presents the history of photography (or the event of photography) itself, split into neat, image-studded clusters.

Clusters, of which there are eight in total, include “The photographed person was always there,” “Iconization is preceded by collaboration,” “When a community is at stake” and “Potentializing violence” among others. Each lays out a potential history with its revisions, guided by the photographs that have been remembered and the ones that haven’t too. It’s an education in constant dialogue with the six featured photographers, weaving a web between past and present, established practice and new or non-canonical ways of working.

In one cluster, for instance, Julia Margaret Cameron photographs her friends as historical, biblical and literary figures, transforming poets, playwrights, and even neighbors into the kings, queens, and tragic heroines of yore. Below them, Edward Curtis’ photographs of Native Americans wink out, reconsidered. The angular arms, long torso and heavy breasts of Georgia O’ Keefe—as photographed by Alfred Steiglitz—push the viewer to revisit what consent and mutual recognition means.

And then, viewers are drawn right into the present. On the wall nearby, Solano creates scenes that may have taken place during Paul Gauguin’s visit to Panama in the late 19th century, drawing sharply on the painter’s “absurd search for subjects, who he believed could help him connect with ‘primitive’ life.” Spread across a single wall, women with painted faces, bodysuits, and thick black hair pose on their knees, stomachs and arms. They look back directly at the camera, as if to say, are you kidding me?

| Rachelle Mozman Solano, Child Pose, 2016. |

Solano is whip smart and bitterly funny, placing her subjects in many of the same absurd, sexual and infantilizing poses that Gauguin became known for, then breathing new meaning into them. As subjects engage the viewer, their bodies are no longer up for visual consumption. Works, meanwhile, bear titles taken from Gauguin’s own accounts, claimed for a kind of visual callout culture. They are amusing and moving all at once, uncovering the farcical, false, misplaced, and horribly damaging nature of the artist’s nostalgia.

One room over, that dialogue takes a different tack, placing Ed Gendron’s photographs of World War Two reenactors across the room from a cluster that explores the afterlives of photographs, photographers, and the subjects pictured in them. From one wall, curators explore what happens after the photograph is made iconic, tracing examples that range from Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” to Nick Ut’s long relationship with his Vietnam-era subjects, much richer than the images might lead a viewer to imagine.

| Installation detail of Ed Gendron's "Untitled (Lunchtime at Airshow)," 2017. |

On the other, Gendron adds his own layer to that narrative, chronicling hours in the lives of World War Two reenactors with bright yellow stars stitched to their clothing and SS uniforms neatly pressed and ready to go. One Jewish reenactor, a Catholic woman named Teresa, explains in an accompanying film that it's an effort not to let the human side of the Holocaust be forgotten.

The images, which catch them in action and off the clock, are as compelling as they are unsettling: Teresa smiles, looks over her shoulder with big, bright eyes, her kids scarf down fast food on a lunch break. In another, she clutches them close as a Nazi soldier walks by their window, patrolling the street. All of them beckon in rosy, highly saturated color, jarring when one considers the reality they are portraying. Gendron’s video, Playing Soldier, runs on loop beside the images.

The format is thematic rather than chronological, which gives viewers an acute (and, in this case, accurate) sense that photographic movements do not follow rigid historical boundaries but overlap, inform each other, and fall in and out of style with the same frequency as shoulderpads and overalls.

It makes for cross-temporal, non-Eurocentric connections: Faroq’s stirring and resilient images from Yemen: Unseen Beauty in Times of Destruction (pictured at left is her "Untitled (Taiz Series)") find resonance with new interpretations on and challenges to Steve McCurry, Kathleen Cleaver and Jean-Martin Charcot as well as Omar Imam, Jonathan Torgovnik and Wendy Ewald.

Nearby, Daniel Eugene’s DRAG/RACING series raises questions about the photographer’s lived experience within the medium—as do works from artist Susan Mieselas, A.H. Wheeler and Cindy Sherman in clusters beside the works. In the portraits, Eugene has captured two radically different, evolving and simultaneous parts of his life: his love for car racing and the blue-collar crowd it draws, and his love for and participation in the city’s drag scene. The photographs are are grainy and bright, with a depth that makes it hard not to reach out and touch them.

It’s a juxtaposition that he brings together with both humor and harmony, complicating it further with the introduction of his drag persona, Sorcia Warhol. Beside Warhol, the scene is so very banal: Lucia Virginity checks her phone is a sparkly gold dress, two figures chat in the background. Nearby, a similar configuration takes on new meaning: four men sit and talk in their car racing gear, one of them standing in an imperfect contrapposto at the far right.

| Installation detail of Daniel Eugene's DRAG/RACING #3. |

Collaboration doesn’t feel particularly revelatory—photographers have long been thinking about and challenging their relationship to the people, places and things they photograph—but it raises timely questions for its audience. Among them are the evolving role of social media on the photographic index, the politics of identity and reclamation, and the circulation of an image beyond (or perhaps as an extension of) its intended use.

Collaboration: A Potential History is also an evolving project, speaking to the very collaborative nature of what the show is trying to do. Artspace has installed the show with a series of questions and hashtags that invite viewer participation. Those responses will be posted on a reserved wall through the end of the show.

In that sense, it’s very meta: organizers have handed a critical framework over to New Haven artists, some of whom riff on the same conventions that the show is critiquing. In Atherton’s work, for instance, the artist draws on the history of photography and film to track the passage of time, doling out spoon-sized portions of New Haven in the artist's Everyday Encounters Series.

It’s a partial game of citywide I-spy with a keen lens, with references to high theory (Walter Benjamin and Franz Hessel, who both wrote on navigating cities at pedestrian scale) and popular culture, from the film Night In The City to magazine spreads and album covers.

| Detail, Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez and Monique Atherton, Monique Atherton Walk Sequence by Ruby Gonzalez, 2018. |

Many of her subjects are casual interlopers, who appear to be passing through a city that is just temporarily theirs. The use of Chapel Street is particularly interesting—it’s both a main artery and physical hub, where socioeconomic worlds collide at Church and Chapel, State and Chapel, and on the far edges of Wooster Square.

Others are not people at all but fleeting objects: fireworks that explode into bursts of hazy color, big overpasses that Atherton experiences on her own walks. These decentralize the power and focus of the photographer: they invite in studio assistant Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez by name, and need her help to complete the sequence.

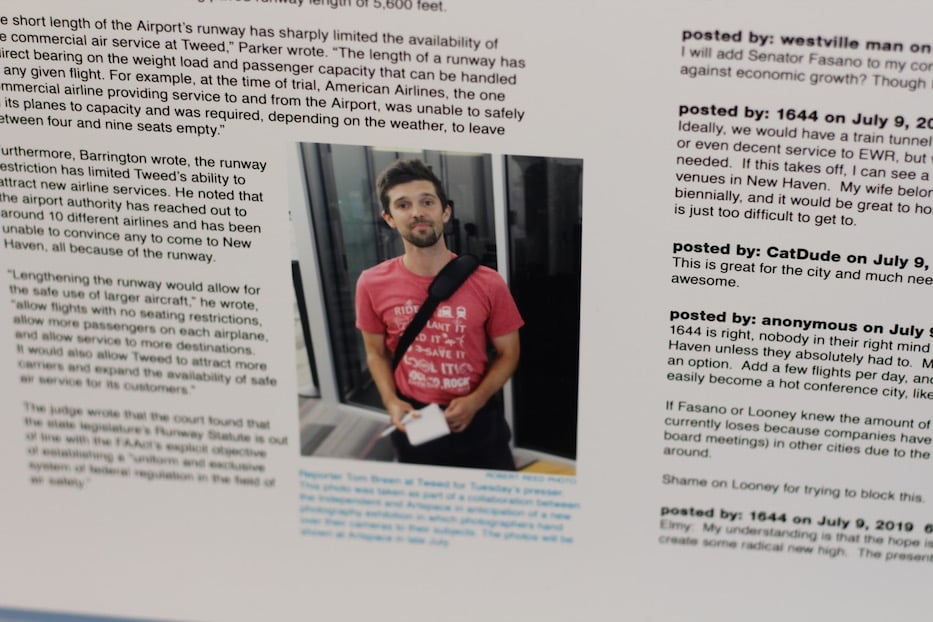

That extends to work from Thomas Breen, in which the New Haven Independent reporter has turned his camera over to the people he is covering and invited them to photograph him. Gone is his technical line of defense, leaving him open to the same public view (and by extension, visual scrutiny) that city officials and community members alike may find themselves in at public events and meetings.

Some of the collaborators seem exhausted with the project before it starts. Transit czar Doug Hausladen has taken a wide shot of Breen in motion, his mouth twisted and a huge gap of empty space above his head.

| Thomas Breen and Robert Reed, "Court Overturns Tweed Runway Limit," 2019. |

Others, it seems, have turned to the lens as a form of humor and candor. In Leslie Radcliffe’s photograph for “Homeless Youth Quest Prevails,” Radcliffe has waited until Breen bites into a huge sandwich, his jaw reaching wide. In Robert Reed’s “Court Overturns Tweed Runway Limit,” the reporter looks exhausted and fed up, like it’s his third assignment of the day and he’s already missed a deadline.

Together, the images tell a story of what photography has been, what it is, what it might be. It’s full of tidbits that double as an education, delicious for those who have a grip on the history of photography and those who don’t. And it makes a proposal that feels timely, particularly in the age of smartphones and Instagram: to let the learning keep going. To marvel at its adaptability and be more cautious of its rapacious eye.

Perhaps even more important, to be a part of its evolution.

Collaboration: A Potential History Of Photography runs through Saturday Sept. 14 at Artspace New Haven, 50 Orange St. The exhibition ends with an all-day closing event that includes an artist’s talk and workshop. For hours and more information, visit Artspace’s website.