Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Ninth Square | Visual Arts

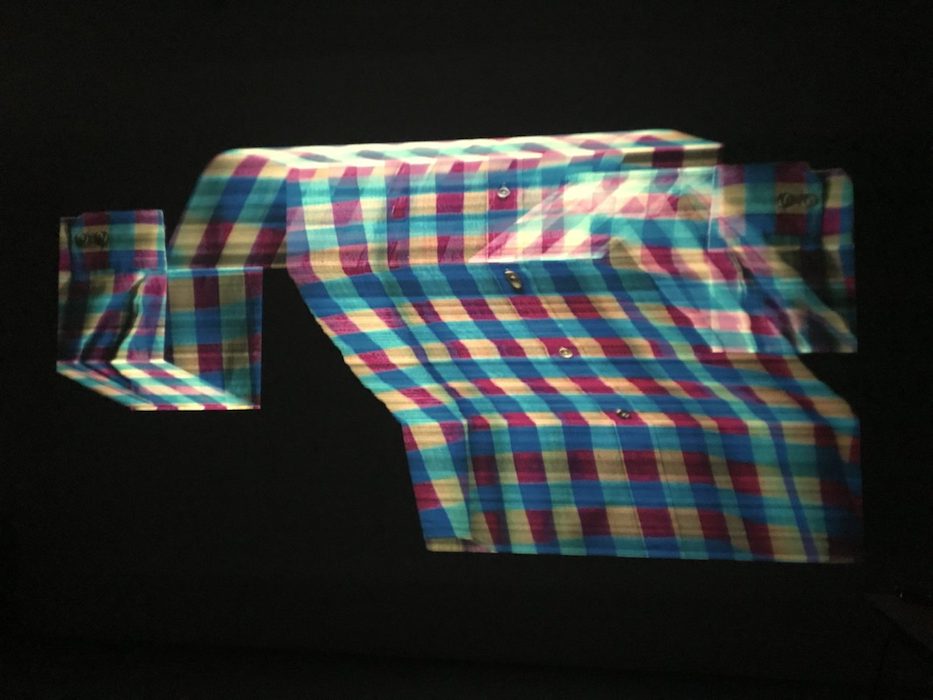

| A detail of Blinn & Lambert's Romantic Love. Artspace New Haven Photo. |

First, it is just a block of floating color, wrapped in bands of pink, teal, yellow. The shape shifts: a sheaf of color winds upward, a bright beam of colored light. It fades into itself, reemerges as a flat arch of color. The clean click and whirr of a projector becomes a precise soundtrack. It’s a gallery that feels more like a cathedral, where fractals of light fall over the pews.

Blinn & Lambert’s Romantic Love is part of Strange Loops, running now through Feb. 29, 2020 at Artspace New Haven. Curated by by Johannes DeYoung and Federico Solmi, the eight-artist exhibition draws its title from Douglas Hofstader’s 2007 book I Am A Strange Loop, an exploration of self-actualization and self-realization amidst a rising tide of new technology.

The curators have also taken context from Émile Durkheim’s 1897 Le Suicide, a sweeping social study on suicide in which the French sociologist introduced the concept of anomie, or “the malady of the infinite.” It’s a neat bookend in the show: over 100 years before Hofstader was writing (and close to 80 before the first mass-market computers), Durkheim was already warning his public about the rise of the machines.

“As artists working within the trappings of twenty-first century media culture, we share interest and concern in the social and psychological effects of media culture at large,” reads a statement from DeYoung accompanying the exhibition. “So the paradigm of the self-referential loop feels like an especially relevant point of departure.”

| Detail of Ilana Harris-Babou’s Reparation Hardware, a multimedia installation with video and 18 accompanying pieces of "hardware" that appear in or are associated with the video. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

If it’s an ambitious and sometimes abstruse framework, artists break through it to deliver a show that is at turns thought-provoking, cheeky, and sublime. Visible from the street, Ilana Harris-Babou’s Reparation Hardware glints in the light, drawing one closer. Below the video, a series of ceramic hammers are arranged on a shelf, some broken and reassembled into lamps with exposed bulbs and bulbous necks. Everything is painted in a thick glaze, as if the artist has applied layers and layers of egg-wash.

The video, a riff on Restoration Hardware’s “Salvaged Wood” collection, quickly becomes a biting and whip-smart take on the nonexistent state of reparations in the United States. Describing the project on screen, Harris-Babou explains that each family will get 40 acres of tillable land, the same legislative promise that was made and then broken to grant “40 acres and a mule” to formerly enslaved people after the Civil War.

“Reparations, what is it,” she says in a voiceover as her hands press down on soft clay and piano rises in the background. “It’s a way to give back a little. With reparations, you can take the past into your home tastefully. Truly dealing with how we live, recognizing what another’s difference is, is something that hasn’t happened yet. Until now.”

As she continues, the politics of spoof dress down the absurd, exploitative, maddening legacy of structural racism and economic deprivation in this country. Wide pans reveal her taking photographs of used wood in a grassy field, tromping through nature, standing regal outside an old barn with a rake in her hand.

When she announces that she is “searching the landscape of our nation for its most authentic histories,” the camera stops on a cow unleashing a thick, hot stream of urine onto the farmland below. It’s spot-on in showing how absurd the premise of the American Dream is for those not born into, wrapped around, or able to claim their whiteness.

Further into the gallery, artists have zeroed in on self-realization in the digital age, often binding the two. In Artspace’s back room, artists from the Virtual Dream Center have created a three-dimensional, digital rendering of Artspace, accompanied by a virtual reality headset and controls with which viewers can navigate the gallery. In this digital white cube version of the space, new works of art take over on the walls, some of them bright and huge. Palm trees and columns of water shoot up from the floor.

| Critic Judy Birke and Artspace Gallery Director give the Virtual Dream Center's 2019 Strange Loops for a test drive. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

In the otherwise dark room it glows white, like a weird new-agey sort of night light. It’s installed with crisp museological conventions, and feels like both a fine art object and an artifact of its time. And yet it works for a site specificity and play-like quality: it presents an Artspace that exists and also does not exist at all, placed in a sort of liminal space. There are ways to cheat this Artspace just like any other video game:

“It’s the capacity to make something where the only limit is one’s imagination,” said Artspace Gallery Director Sarah Fritchey at a press preview Friday.

It’s a sort of unexpected pendant to Blinn & Lambert’s Romantic Love, a 23-minute geometric ballet split between two slide projectors. In the piece, artists Nicholas Steindorf and Kyle Williams have set up the projectors to beam images onto the same screen, displaying the step-by-step, slowed down folding of a plaid shirt. In front of the screen, they’ve installed a series of soft seats, inviting their viewers to sit down and stay a while. They’re cushy and very modern at the same time, like a church pew has found an old-school movie house.

The piece comes off as a marriage of new and old technology, particularly in photography, film, and the study of the moving image. One moment, the color saturation and blocky pattern may look less like fabric and more like glitch art, where the code is broken and color drips out of a pattern. Then the image shifts—the projectors whirr and click—and the shirt is full of light and motion, almost undulating.

It shifts again, frames melting into each other. It recalls Eadweard Muybridge, or early attempts at cinema where film was tinted by hand, frame by frame (it’s neither of those things, perhaps a reference to the strange loop that is art history itself). Because of the installation’s length, the artists have demanded that their viewers slow down and put their phones away, as not to miss a single transition. Set in an otherwise dark, cavernous gallery, it becomes borderline spiritual, an entryway to the flow state if not also something sublime.

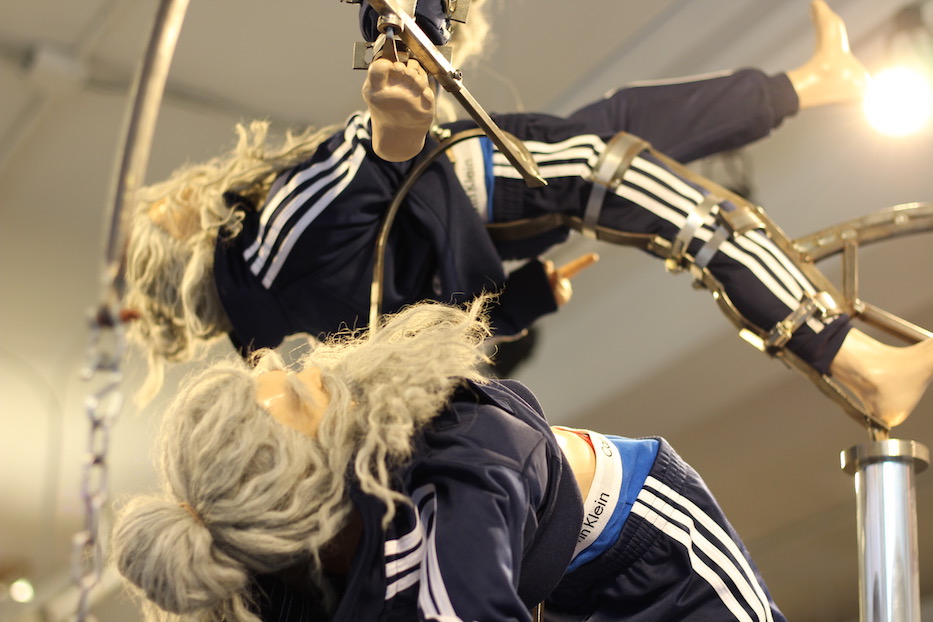

Other pieces in the show take up humor, wit, nostalgia, and the role of a human in their quickly-changing built environment. From artist Jon Kessler, curators have installed It Takes A Global Village Idiot, a 2018 work in which bearded plastic dolls decked out in Adidas tracksuits climb and tumble from the work’s careful scaffolding. It’s built as a mobile, meaning that every part of the piece maintains its balance.

| Detail, Jon Kessler's It Takes A Global Village Idiot (2018). Lucy Gellman Photo. |

The piece is quite funny: for something about stasis, it looks as though Father Time has gotten lost in a WalMart and finally started to unravel. But it’s also biting: it seems that the reason the bearded doll, dressed in the symbols of late-stage capitalism, can start climbing up once again because of his age and his whiteness. Even in his fall, he’s dressed to get up and start running forward again.

One room over, it’s a sharp contrast to Ana María Gómez López’ Punctum studies, in which she has become that living cycle. Unlike the plastic doll, ascending and tumbling, she has made herself into a vibrant sort of loop, using advances in medical technology to externally circulate her own blood.

The images pair old and new yet again, in a way that is wildly different from Romantic Love. The Punctum images wouldn’t be available without modern medicine, and yet they don’t feel especially modern. Gómez López is joining a whole chorus of artists who use their bodies as substrate. Instead, they feel almost early modern, as if they are an answer to so many questions artists asked about blood and the circulatory system centuries ago.

| Detail, installation of Sam Messer's Thin Realm (for Jake Berthot), 2016. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Artist Sam Messer, who is also a writer, has included several larger-than-life paintings and one sculpture of his typewriters, a reference to the technology on which he once conducted his own work. Of all the works in the show, they are a visual treat to look at, inviting a certain intimacy in spite of their massive size. Viewers can get close to the works, inspecting thick layers of oil paint on the keys, or the brilliant color of Thin Realm as it spans the better part of a wall.

His huge, bronze Olympia takes on a humanoid quality, her keys wide open as if they are a smiling mouth with two too many rows of teeth. The roller knob and carriage return look surprisingly like ears, one lobe pulled further than the other. The title is smart: Messer conjures not only the brand of typewriter to which he was so faithful but also Édouard Manet’s painting of the same name.

Since the painting shocked audiences in 1865, that Olympia has gone on to be an exhausted teaching tool more than a piece of living art. So will this once-dear object suffer the same fate?

| Detail, Teddy Mathias' Hapticscapes in action. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

It’s a question that artist Teddy Mathias, a recent grad of the Yale School of Art, also seems to ask as he brings the show literally home. Near the back of Artspace, he has arranged his Hapticscapes, a series of old, broken pieces of road that can be scanned with digital “divining rods,” long rods that use an app read the asphalt for distinct sounds and vibrations as they pass over it. The sounds change: clip-clopping boots, staccato footfalls, muffled footsteps that are slow enough to be a heartbeat.

As the pieces chatter with Sarah Oppenheimer’s time-based diagrams one gallery away, Mathias also presents what he calls the “assisted fossilization of urban environments”—close to 200 newly pressed “fossils” of New Haven surfaces, made from balls of clay the artist carries in his pockets on night walks around the city.

Spread out like a display in a museum of natural history, the pieces delight and entertain: they are a game of I-spy centered largely around the city’s Ninth Square neighborhood. They are also a time stamp on a city that is losing history: these bits of tile, sidewalk, and uneven pavement may all be replaced as luxury developers continue to eat up downtown.

| Detail, Teddy Mathias' Modern Fossils of the City. The works were pressed specifically for this exhibition. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

That transformation is also part of Mathias’ process: the artist hopes to bury the fossils after the show, so that they may one day be unearthed and seen themselves as remnants of the oast.

“It sort of forces you to reconsider your relationship with the built space,” he said on a recent visit to the gallery.

Taken together, the works in Strange Loops make a viewer wonder if the future is here—if it's always been here—and if it’s something humans need to step back and and recover from. One leaves the show questioning their reliance on technology, their role in systems of oppression and adaptive reuse, their relationship with the literal space around them. They check out the Virtual Dream Center and remember to be grateful for their sea legs, and the very real, physical gallery in which they stand.

In the best of circumstances, they put their technology down, and look.