Downtown | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Visual Arts | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

W.E.B. Du Bois, Georgia, and His Data Portraits runs at Artspace New Haven now through June 26. Lucy Gellman Photos; all work is Artspace's.

The data unspool a story one line at a time. Under a heading that reads “Occupations Of Georgia Negroes,” over 98,000 free Black men are rendered in a sturdy red line, its tail curving into a U at the end. Beneath them are 63,012 farmers and planters, the line still steady. Then the lines start to shrink, all the while revealing merchants and messengers, blacksmiths and barbers, educators and engineers.

In the empty spaces, tinted yellow by time, is a story of land theft, de facto segregation, white supremacy and historical omission—as well as upward mobility and economic gain—that is over four centuries long.

The work is part of W.E.B. Du Bois, Georgia, and His Data Portraits, running at Artspace New Haven now through June 26. Curated by Lisa Dent and Simon Ghebreyesus, the exhibition presents Du Bois’ 1900 data visualizations as both sociological texts and compelling works of modern art. In so doing, they make a strong case for reparations, critical race theory, and more comprehensive teaching of Black American history that holds up through today.

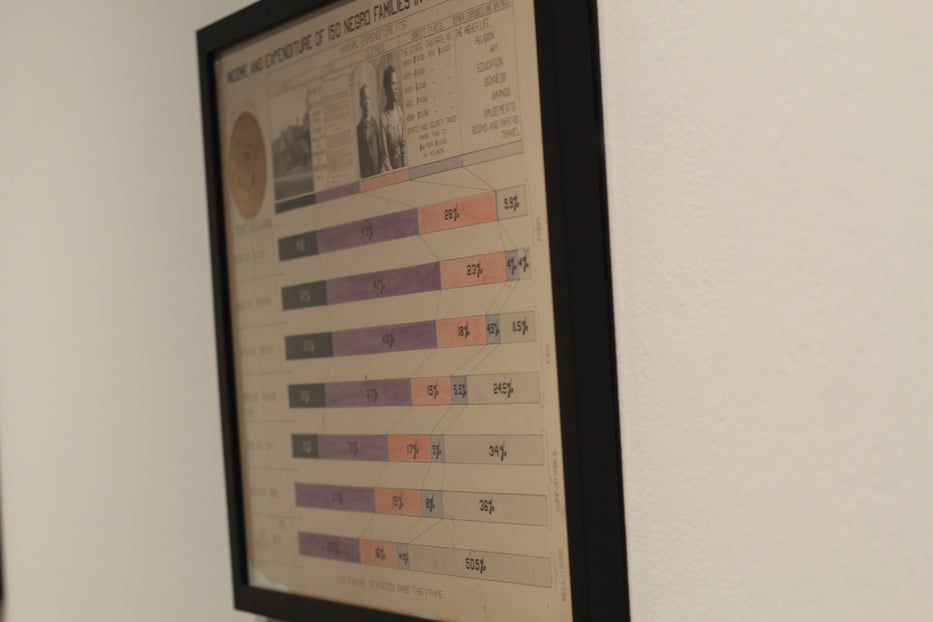

In the gallery, Dent and Ghebreyesus have divided the show into four sections—”Migration,” “Property,” “Family,” and “Work”—to give viewers a sort of road map to the data. While the works are over a century old, they feel wholly modern—particularly alongside Theaster Gates: Light of Progress and Dana Karwas: In A Heartbeat. Both artists build on the legacy of Du Bois’ life and work.

Du Bois’ data portraits were born at the turn of the twentieth century, in preparation for the Exhibit Of American Negroes at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. At the time, the 32-year-old sociologist was on the faculty of Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), an HBCU where he worked from 1897 to 1910. He had already penned his realization of double consciousness, which may be as relevant in 2021 as it was in 1900.

Within the Exposition, the Exhibit Of American Negroes became an educational antidote to a parade of racist stereotypes—and to the way Black people were depicted in most American print media and popular culture. The portraits, done with students and researchers at the university, were the first of their kind to document the lives, professions, marital status, religious traditions, patterns of land ownership, and migration of free and formerly enslaved Black Americans in the United States. They appeared with stately photographs of Black Americans in Georgia, later referred to by some curators as “The Paris Albums.”

Within the Exposition, the Exhibit Of American Negroes became an educational antidote to a parade of racist stereotypes—and to the way Black people were depicted in most American print media and popular culture. The portraits, done with students and researchers at the university, were the first of their kind to document the lives, professions, marital status, religious traditions, patterns of land ownership, and migration of free and formerly enslaved Black Americans in the United States. They appeared with stately photographs of Black Americans in Georgia, later referred to by some curators as “The Paris Albums.”

While they are sociological texts, the portraits double as economical, modernist compositions, as interested in the presentation of data as they are in its methodology and application. Together, they make clear both the progress of Black Americans in the years following emancipation and the devastating and enduring costs of chattel slavery. They also all but predict white nationalist power grabs and centuries of economic disenfranchisement of Black Americans that follow.

Early in the series, Du Bois situates the viewer with color-coded migration maps of what is now recognized as the United States. It’s a reminder that all mobility and migration is built on the twin evils of stolen people and stolen land. From there, he explores every aspect of life, from work to home ownership to literacy to conjugal relations.

“His charts filled absences in the archive, accounting for subjects largely overlooked by past sociological inquiries and shedding light on the troubling data behind the late-19th and early-20th century subjugation of formerly enslaved people and their descendants,” write Dent and Ghebreyesus in an accompanying text. “In portioning the graphs into these four interconnected categories, this show prompts contemplation of the systems that have been touted as the keys to Black advancement yet weaponized against Black Americans since this country’s inception.”

How Du Bois documents that data is as interesting as the data itself. In addition to the Exposition Universelle, the year 1900 also marked the inaugural Pan-African Conference in London, at which Du Bois announced that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” The data portraits demarcate, challenge and explode the color line, interrogating its very right to exist. Take for example the aforementioned “Occupations Of Georgia Negroes,” in which he is quick to show that freed Black people are not a professional monolith at all.

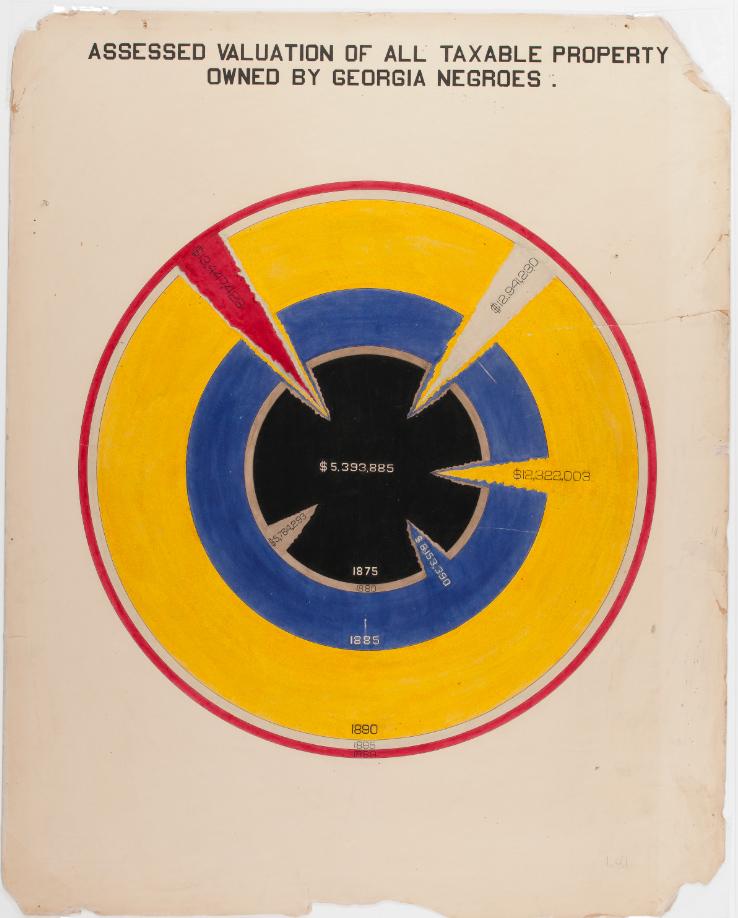

In some of the portraits, thick, colorful slices of data are stacked like jenga blocks, revealing how money, land, race, power, and socioeconomic status all balance precariously on one another. In others, they tilt and tip, as if a level has been set on an uneven wall. In others still, Du Bois has played with arcs, curves, and angles, asking his viewers to take the time and energy required of close-looking.

The presentation reminds viewers that the data is a living thing. There are people behind each line, each block, each stacked and color-coded band, each tightly wound coil. In his “Assessed Value of Household and Kitchen Furniture Owned By Georgia Negroes,” for instance, Du Bois has turned the data into a spiral, its findings wound tightly around each other. As they study each line, a viewer is able to see how quickly furniture ownership—a metric of economic success—increases between 1875 and 1890.

Like the spiral, some of the most interesting portraits to look at are those that experiment with form. In his arresting “Occupations of Negroes and Whites in Georgia,” Du Bois depicts the breakdown of labor not as a full pie chart, but as two obtuse, rounded triangles balanced haphazardly upon each other. His “Proportion of Freemen and Slaves Among American Negroes,” which could be mistaken for an uneven plot of grass from afar, shows the steep and sudden aftermath of emancipation. Even in simple blacks and greens, it is emotional to look at, and to think of how much was stolen from people in the years before.

There’s a sparse, even architectural quality to the portraits that feels far ahead of their time, more reminiscent of the Russian avant-garde than, for instance, the cut-and-dry scientific graphs that Emil Eugen Roesle exhibited in Germany 11 years later. Indeed, the portraits together show a history that is far more kaleidoscopic than a whitewashed, revisionist narrative would have current viewers believe. They pulse with vital, literally vibrant knowledge in a year when students still don’t always learn about Du Bois himself before graduating high school.

Particularly timely—or maybe timeless—is the deep dive into a region that is still written off as consistently more racist than the Northeast, and somehow less worthy of study. Instead of glossing over Reconstruction and the Black South, Du Bois spends time with it, and compels his viewers to do the same. It feels relevant in a two-year period that has seen aggressive attempts at gerrymandering and voter suppression across the country, and particularly in Georgia.

In so doing, the works also challenge a narrative of easy, forward progress that history books and mainstream, white-led and funded media outlets are quick to hold tight to. Du Bois’ “Assessed Valuation of Taxable Property Among Georgia Negroes” still feels searingly fresh 121 years after it was finished, and five decades after the Fair Housing Act was passed into law.

His snapshot of Black newspapers and periodicals, rendered in neat blocks of color stacked in a pyramid, double as an invitation to save existing Black publications, and also envision new ones. The past decades have seen a decimation of the Black press, but also the rise of startup news sites like Blavity, where the V is an inverted pyramid itself.

It is also very much a call to arms, from an Orange Street gallery that manages to bridge past and present with its accompanying exhibitions. While Du Bois’ work feels recent, Gates’ light installations actually are. In drawing from and illuminating the portraits’ legacy, the artist makes sure that they are not lost to history as quickly as the data they represent. Gates also makes it clear that the forces of Jim Crow, redlining, and de facto and de jure segregation are still very much with viewers today, just by different names.

It is also very much a call to arms, from an Orange Street gallery that manages to bridge past and present with its accompanying exhibitions. While Du Bois’ work feels recent, Gates’ light installations actually are. In drawing from and illuminating the portraits’ legacy, the artist makes sure that they are not lost to history as quickly as the data they represent. Gates also makes it clear that the forces of Jim Crow, redlining, and de facto and de jure segregation are still very much with viewers today, just by different names.

In turn, both Gates and Du Bois ask their viewers where they want to be in another 121 years—and what side of history they are on—when it’s their data on display. And, perhaps, what or who is keeping them from getting there. In a city enmeshed in debates around municipal budgeting, affordable housing, and cultural equity, the show is worth a closer look.

Artspace New Haven is located at 50 Orange St. The gallery is open Wednesday through Saturday, 12 to 6 p.m. Find out more at their website.