City-Wide Open Studios | Culture & Community | Erector Square | Fair Haven | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

Jennifer Davies. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Jennifer Davies was perched over a pile of bright, delicate kozo lace paper, her hands moving in time with her words, when Wes Venables noticed a giant, empty water bath covered in painter’s tape behind her. Around them, the studio buzzed with conversation. Against a wall, two visitors gathered around a cast of a millstone that seemed to glow in the afternoon light. Venables, a printmaker at Southern Connecticut State University, waited for an opening.

“Is that the water bath you use with the mold and deckle?” they asked when the moment seemed right. Davies floated over, and took a look. Within seconds, the two were talking about how much tape to use to make the water bath indestructible.

Those lessons, often delivered in casual, impromptu conversations, filled Erector Square on Saturday and Sunday, as the third annual artist-led Open Studios rolled back into the Fair Haven hub that so many makers call home. Held during a month of open studios events, the weekend became a reminder of the power of creative community, from pet rock pop-ups and harvest mandala making to paintings, handmade paper, and photographs that called for a second and third look.

Over 100 artists participated, with thousands of attendees over both days. Earlier this month, other artist-led events included a pop-up at the Ely Whitney Barn, West Haven Open Studios on Gilbert Street and Anderson Avenue, and events at City Gallery, the Ely Center of Contemporary Art, and NXTHVN, where Reverence: An Archival Altar runs through Nov. 23. The celebration continues next weekend with open studios in Westville and Hamden’s Highwood Square.

Top: Artist Jeff Mueller of Dexterity Press at work. Bottom: A visitor navigates the new color-coded way finding system.

“We’re kind of siloed [during the year],” said Eric March, a painter and illustrator who worked with several fellow artists to keep Open Studios going in the absence of Artspace New Haven, which used to run the event. “It's one of the nice things about putting a thing like this together—the creation of community. It's both a community within Erector Square, and then creating that interface with the public.”

The event has been months in the making. Earlier this year, artists Ioana Barac, Niko Scharer and Adriana Hernandez Bergstrom dreamed up bright, color-coded signage (and balloons, so many balloons) for the complex’s eight interconnected, labyrinthine buildings, and helped with a new mapping system that broke the buildings down by floor. March’s brother Peter, who happens to be a user experience expert, offered to do an audit of Erector Square, and added a streamlined wayfinding system and mingling events for artists based on his findings.

Liese Klein, who runs Fire Horse Dojo in Building Five, helped build a scavenger hunt and opened her space to kids, so there was a place to collect prizes and make crafts. Curator Maxim Schmidt, who now works with the Institute Library, enlisted volunteers—many of them young artists and art students themselves—to assist with activities, run welcome and information stations, and help visitors find their way. Throughout the days, an attendee could spot both Schmidt and participants in the hunt buzzing from building to building, in search of the next artist they needed to see ("It's been delightfully nuts," Schmidt said Sunday).

Top: Artist-curators Martha W. Lewis and Maxim Schmidt. "I feel like the energy, in terms of what we've been able to deliver and how we'e able to make this more enjoyable for both the guests and the artists, is getting better every year, as the artists continue to self-organize," Schmidt said. Bottom: Work by artist Noa Cancelmo, who is relatively new to Erector Square.

Sunday, that legwork was apparent throughout the huge complex, as artists, visitors and volunteers alike made their way through the space, some stopping for conversation in the already-narrow hallways as others walked briskly past. Down any given hallway, it was possible, even likely, to simply run into art, with dozens of artists who had popped up in foyers, corners, landings, hallways and on loading docks.

Upstairs in Building Three, artists Noa Cancelmo and Rachel Liu greeted visitors in a quiet corner studio, an open window overlooking the parking lot below. On one side of the room, candles flickered beneath rows of photographs, the images strung up like Christmas lights. In one, a 2022 photo titled Matriarch, a grandmother sat, surrounded by generations of family members who pressed their hands to her heart. In another, a mother held her three children to her chest and soft belly, the tops of her breasts visible. Even frozen in time, the possibility of movement felt imminent, as it often does with squirming littles.

Liu, who was a labor and delivery nurse, doula and childbirth educator before she was a professional photographer, greeted attendees warmly, pointing out photos in which many of them were featured. Before Sunday’s open studio, she’d been up in the wee hours of the morning, photographing a birth at Yale New Haven Hospital. She hadn’t had a chance to stop since. And yet, she seemed totally invigorated.

“I think what feels really good is getting to the essence of who a person is and capturing that. Or not capturing, witnessing that, and getting to give it back to them,” she said. “Most people hate being photographed, but most people want to be seen.”

Scott Schuldt, whose work ranges from multimedia sculpture to large, beaded portraits on fabric, lingered on Liu’s image of the grandmother, amazed by the worlds contained in a single image. He later explained that he was moved by how comfortable the subjects seemed, a testament to the artist’s soft, gentle touch as a photographer, former birth worker and mother herself.

Top: Artist Noa Cancelmo and their largest work, which was completed during their BFA work at RISD. Bottom: Liu's work.

Across the studio, Cancelmo welcomed attendees to a long table piled with paintings and prints, sometimes bashful when the subject of payment came up. Across the table’s surface, colors multiplied: there were abstract prints, done when the artist still had access to a press, watercolor and oil paintings that made earth-toned magic out of dancing squiggles and shapes, modernist designs printed in bright, sky blue with messages like There Is An Infinite Supply of Love.

Born and raised in New York City, Cancelmo did not start making art seriously until they were in their late teens, and sustained an injury that took them out of a serious commitment to dance. At the time, they were just starting their path to higher education, which led temporarily to graduate work in sociology at the University of Connecticut and then a job at the Connecticut Veterans Legal Center (CLVC).

At some point, though, they realized that they wanted to make a career shift, and work in arts education. While still working at CLVC, Cancelmo went back to school, studying at both Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU) and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) to make it a reality. They are now a middle school art teacher in Branford, after student teaching with artist and educator Erin Michaud at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School last year.

As they spoke about their experience, taking time to greet friends and family who came through the studio, it was easy to gravitate towards a large canvas quite unlike any of the others, completed last year as part of Cancelmo’s work at RISD. In the work, a figure sits beside a tree in the tall grass, their legs outstretched. Beneath the orange knit of their sweater, an orb has formed, tinted blue and full of light.

Flowers, white and wide-petaled, drip down on vines, some caressing the figure as others hang in midair. Leaves weave in and out of the tree, leaving a trail of jade, teal and olive green in their path. “It’s a prayer,” Cancelmo said when asked about the work, which sat atop a table of half-squeezed paint tubes and two mugs filled with clean brushes. That’s both literal and figurative: the painting contains excerpts in Hebrew from the Kaddish (יְהֵא שְׁלָמָה רַבָּא מִן שְׁמַיָּא, “May there be abundant peace from heaven”) and references to “Olam Ha-ba,” (עוֹלָם הַבָּא), or the “World To Come.”

“I was struggling a lot with like, ‘What is my role at this moment in time?’” recalled the artist, who is both queer and Jewish, and found themselves in a place of deep heartache after Hamas' Oct. 7, 2023 attacks in Israel and ensuing war, which has upended lives and families across multiple man-made borders, and left tens of thousands of Palestinians dead. In the painting, rendered in a kind of lush and surreal dreamscape, “it’s my ancestors and me and my future and the future,” they said.

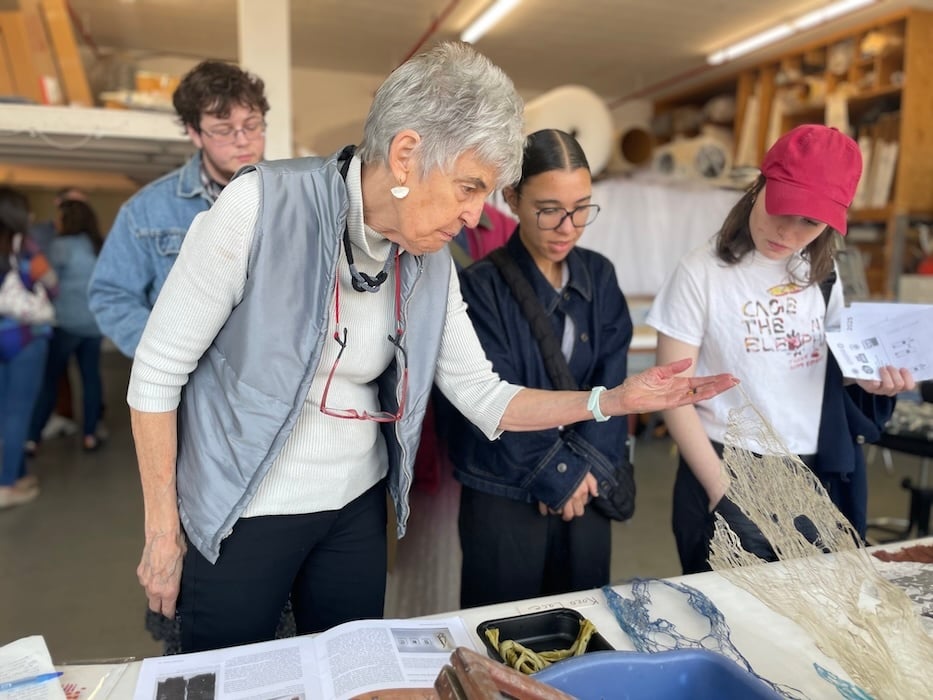

Top: Davies in teacher mode, which comes to her naturally. Bottom: The paper cast of the Story Creek millstone, in all its glory.

Just a few doors down the hall, Davies also tapped into that same sense of wonder with her handmade paper compositions, some large enough to fill a portion of the wall. At a table normally reserved as a workspace, she had laid out the steps that go into making kozo paper, from a bundle of untreated branches to a pounded down, damp version of the pulp and stringy, almost hair-like fibers that emerge after they have lost their lignin.

An artist from the time she was young—“I never could do anything else,” she mused—Davies fell in love with paper making decades ago, inspired by both the labor behind the craft and the importance of the medium itself. If asked,“most people don’t know anything about paper making,” she said. And yet, she sees paper as vibrant and revolutionary: the creation of paper led to printing, then to books, and then to the wider dissemination of knowledge.

As she chatted, visitor Ike Lasater made his way over to a thick paper cast of a millstone that Davies completed several years ago in Story Creek, Branford. The piece, from both far away and close up, is something of a revelation, with fibers that are still visible, marbled blues and blacks, and defined ridges where the stone once likely ground wheat.

“Is this a—” Lasater trailed off as the artist came over to look at the work with him.

“It’s a cast of a grindstone,’ Davies completed his sentence. She explained that after finding the stone on a walk through Stony Creek, she had done a paper cast in a single day, working in segments from morning to night until the whole face of the stone was covered. “You bring the pulp, and it’s all beaten up, and you slap it on,” she said. By the time she finished, it was dark out.

When she made the cast, Davies didn’t know if her experiment would be successful. She cordoned off the area with a sign, and hoped that other passers-by wouldn’t tamper with it. When she came back days later—it took about a week for the pulp to dry—the cast “popped right off.” She was delighted by it, down to the fingerprints that remained visible.

Minutes later, she was back in that educator role, as art students from SCSU made their way through the studio (Davies is a natural teacher: she’s given many classes at the Center for Contemporary Printmaking and Creative Arts Workshop). Venables, a senior at the university who is studying printmaking, gravitated over to a giant waterbath, listening as Davies doled out tips for building, maintaining and using one.

No sooner had she finished that than she was talking students through the process itself, which begins with a bundle of branches, and includes boiling them in soda ash (Davies uses a lobster pot on a grill), beating them to a pulp, re-hydrating the pulp, and running a mesh screen through the water to collect the fibers. “It’s nice to show people” the process, she said.

“I love having this weekend,” she added after they left.

Sydney Harris and his grandson, Brooks Harris.

Elsewhere in building three, visitors milled around cartoonist Sydney Harris’ studio, stopping every so often to pay their compliments to the artist as he chatted with his grandson, Brooks, on a couch in the corner. Born and raised in Brooklyn, Harris started making art in his teens, after dropping out of Brooklyn College. Working out of his childhood bedroom, “I stuck to it,” he remembered, motivated enough to continue with the form until he sold his first few cartoons.

Decades later, they’ve been widely published, in magazines and newspapers ranging from the New Yorker to Playboy to the Wall Street Journal. A quick look around the room, in which there are boxes and boxes of framed cartoons, reveals why: Harris has a kind of sharp, sometimes curmudgeonly and old-school humor that is distinctly Brooklyn, and also from an era that rarely feels accessible anymore.

For Harris, Open Studios is also something of a full-circle moment: it was while viewing art at Erector Square over two decades ago that Harris “said, I could paint,” and moved into a space in the building himself. For years, he would start his days at the studio five or six days a week, working on his paintings for three hours before going home to do his work as a cartoonist.

Artist Hafsa Nouman.

Throughout the day, artists popped out of the woodwork like this, weaving an intergenerational tableau in the process. On the other end of Erector Square, Hafsa Nouman was still getting used to her studio, after just a few months in the space. A recent graduate of the Yale School of Art, Nouman moved into her studio, which she shares with the artist Jam Yoo, in July of this year.

Sunday, she floated through the space, alternating between chatting with a friend who had come into town for the weekend, and talking to fellow artists and visitors who had questions about the work. Every so often, a few pint-sized viewers rolled through, and Nouman fished lollipops out of a glass jar in the center of the room. Then she went back to discussing her work, including a long, papered-over section of the wall with tape in criss-crossing and geometric patterns.

“I always knew I wanted to be an artist,” she said when asked when her practice started. Born and raised in Lahore, Pakistan, Nouman grew up as the eldest of three, always interested in visual art and self-taught for years. After high school, she attended the College of Visual Arts in Lahore, then landed in New Haven through her studies at Yale. When she graduated in May, she decided to stay, making the city her temporary and artistic home.

Printmaker Oi Fortin welcomes visitors.

In her work, which often plays with the viscosity and sheen of oil paint, Nouman focuses on the impact of colonization on both visual culture and infrastructure and development in Pakistan, with work that has included first-person interviews and deep research. She is interested, for instance, in how traditional ritual symbols and patterns were, under colonial rule, adopted into wrought iron gates and fences “used to create barriers” between an increasingly tiered and segregated society.

Then, after Partition in 1947—by which Pakistan was legally recognized as its own country—those patterns became common in domestic architecture, a kind of visual continuation that was also a reclamation.

She looked to the much more recent example of homes that were razed during the privatization of Pakistan’s railways, a shift that has come—and is an ongoing flashpoint in the country—with pressures from global entities like the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and World Bank. One of those homes belonged to her grandmother Shamim, who she refers to affectionately as Bibi. Over the summer, she had the chance to go back to Lahore and talk to residents about what the changes in the built environment meant for their everyday lives.

“These stories keep repeating over and over again,” she said. Around her, the studio seemed to sigh heavily in agreement: canvases looked back with glossy coats of blue, grey and yellow, almost wet when the light hit them the right way. Footfalls echoed through the hallway outside, some making their way in. Although it had been only months, she seemed right at home, at ease with stretched canvases, shelves and dropcloths, and paint still waiting to be used.

Artist Fethi Meghelli's studio.

In a studio down the hall and up a flight of stairs, artist Fethi Meghelli sat amongst his creations: small, unpainted sculptures that he refers to as his “visitors,” tiny handcrafted animals and people, collages that bring together paper clippings and shimmering fabric, drawings of generations of people fanned out across the wall. For Meghelli, who has worked in Erector Square for the better part of two decades, it’s a chance to celebrate the breadth of artmaking that a single person can do.

As he walked around his studio, the walls packed with art, Meghelli remembered his childhood in Algeria, during which he realized that he wanted to be an artist. As he tells it, he was in the first grade, and a teacher encouraged him to draw, putting out paper and crayons for the students. Meghelli, then just 6 or 7, covered the paper with rolling, deep blue mountains and a single red bus with people inside.

“In the end, the teacher said, ‘We’re gonna hang it on a bulletin board,’” and the rest was history, Meghelli remembered. He was hooked. He attended the School of Fine Arts in Algeria, and then went on to study in Paris. It was there that he met his wife, an American named Barbara Greenwood who just happened to be abroad. When she landed a job teaching French at a then-nascent High School in the Community, he moved to New Haven with her in 1974.

For years, he worked out of an attic studio, teaching charcoal drawing at Creative Arts Workshop (CAW). Then 15 or so years ago, he moved into Erector Square, he said. He loves Open Studios weekend, because it brings in people who ask questions about his art.

.jpeg?width=933&height=622&name=OpenStudios_2025%20-%201%20(2).jpeg)

"I’ve always been doodling," said 11-year-old Edwin Manton.

If Meghelli (and many artists at Erector Square) is decades into his career, others are just starting it, and looked to Open Studios weekend as a launchpad. Close to what March described as a “bottleneck” in Building Six, 11-year-old Edwin Manton presented his artwork for the first time, sharing a table with his mom, the artist Megan Shaughnessey.

A student at Spring Glen Elementary School, Edwin said he’s still not sure why he originally gravitated toward art, but he quickly realized that he was in love with it. Sunday, he was one of a few young artists with work on display, including 5-year-old rock painter Abraham Svenningsen Omonte a few buildings over.

“I don’t know if it’s the fact that my mom is an artist, but I’ve always been doodling,” Edwin said. At some point, those doodles took on a life of their own. Often, he said, the ideas come to him all at once: a disembodied, shaded hand, open and waving; a Miyazaki-esque crow, its beak long and curled; a ramen shop beside a flowering cherry tree, the branches shaded pink.

A closer look revealed the shop in fine detail: five red hanging lanterns, each cloaked in a thick black line to show shadow, big glass jars of pickled vegetables, fitted with fabric over the lids, stacks of treats in the window below. A yellow background made the shop pop, its brown awning standing out.

Even as the day was winding down, the building seemed to teem with life. In one studio at the end of Building Three, adults lingered at a station for Harvest Mandalas, a credit to the environment that artist Nadine Nelson and EcoWorks had created. Across the lot, almost a dozen attendees made their way to Ekow Body Skin Care & Wellness, where owner Candice Dormon was winding down the day with line dancing.

“Ok! Right, left, right, left, turn, right,” Dormon was saying, and attendees followed along, some giggling as they learned the moves. In a minute, she would put on Fantasia’s “When I See U,” her visitors singing along by the end of the song. But for a breath, she seemed to soak everything in, savoring the moment.

For her, the weekend represented a chance to meet more of her Erector Square neighbors, which she’s made an effort to do since officially opening her doors last month. Just like visual artists in the building, she also took the the days as a chance to experiment, give free classes, and talk about her work, including with couples who hadn’t danced together for years.

“It’s been a great flow of people all day,” she said, remembering an elderly woman who insisted she was too frail to dance, and was up and moving by the 15-minute mark. “My heart is so full. Maybe this community hasn’t had this sort of experience before … it just feels good to be adding this layer to the Erector Square community.”

“That dance joy,” she added, “is contagious.”