She Was My Home, a mixed media art piece by Candyce “Marsh” John. Abiba Biao Photos.

The gallery is full of light. To the left of a large, collaged canvas, a mobile spins slowly, studded with brilliant yellow sunflowers. Beneath it is an altar furnished with photos, candles, and mementos from a life well lived. Some days, music and conversation waft through the gallery, giving it a sense of being in bloom.

But it is the canvas, with nods to graffiti, to the Bible, and to documentary photography, that immediately draws a viewer in. Bursts of pink, yellow and green cut across the surface, framing the late Ella Nora Price as she looks straight ahead. Her face is young, determined; a yellow crown hovers above her head. On the right of the canvas, the words of Psalm 23—The lord is my shepherd, I shall not want—scroll across the canvas in neat, contained lines of text.

Welcome to Reverence: An Archival Altar, now running at NXTHVN at 169 Henry St. through November 23. The months-long project of curator and artist Arvia Walker, it highlights eight New Haven families who have loved and lost fiercely, bridging past and present in the process. Last Saturday, the exhibition opened with an hours-long reception; read more about that here.

Artists include Kulimushi “Kuli” Barongizi, Sydney “Syd” Bell, Marquis Brantley Sr., Shaunda Holloway, Candyce “Marsh” John, Jasmine Nikole, and Mel Phillips. Pieces in the collection range from paintings to mixed media.

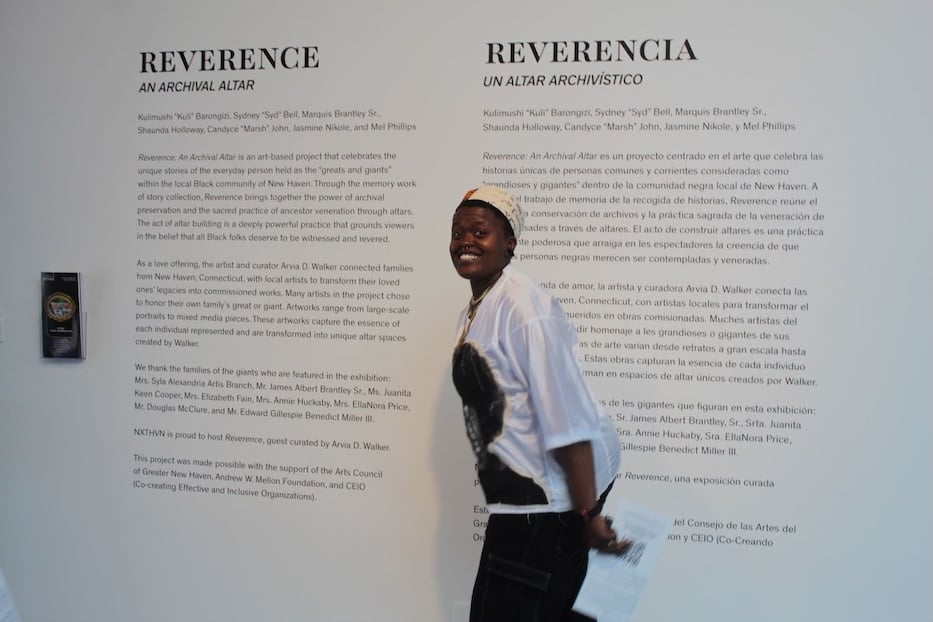

The artist Marsh at an opening last weekend.

The exhibition goes beyond displaying art to the public, and serves as a large-scale archival project using both qualitative methods and deep, sometimes palpable emotion. Artists, for instance, have collected photos and interviewed loved ones, making each artistic process into a sort of translation project.

In one work, artist Frances Branch-Walker (with help from Barongozi and Kaelynne Hernandez, who have added a layered and lush portrait) pays homage to her mother, Newhallville matriarch Syla Alexandria Artis Branch, with both an altar and installation that includes Branch’s photographs and recordings.

During her life, Branch was a celebrated pianist and musician, with a gift that she passed on to her grandson, the virtuosic Paul Bryant Hudson. For close to five decades, she served as the minister of music at Christian Tabernacle Baptist Church, which now sits in a squat brick building on the New Haven-Hamden border on Newhall Street.

She played up until the very end of her life, recording a double album of 50 songs on her 90th birthday. Hudson, who first performed with her when he was three years old, brought that history full-circle Saturday, as he blessed the crowd with a set that was part-music, part benediction.

“There’s so much that she just gave from her spirit to mine,” he said of her in a 2020 interview about her life and legacy.

Saturday, curator Arvia Walker revealed that a strong motivation behind the exhibition was to highlight stories from New Haven. For over a year, she has been working to help New Haveners—particularly Black New Haveners—find, document and archive their histories. This is a continuation of that work.

“The center of Reverence is that all Black people deserve to be witnessed and to be honored and deserve reverence no matter how big or small our story may seem,” she said. “To someone we are a great or a giant.”

“As we’re honoring the people that helped us become who we are, what are we doing in the moment to be good ancestors to the people that are coming after us?”

All around the gallery, a viewer can see that in real time. There are alters to Elizabeth Fain, another Newhallville matriarch who lives on in the writing and advocacy of her granddaughter, Sun Queen; to Mr. James Brantley Sr., whose grandson Marquis has kept his flame burning a series of larger-than-life canvases; to Annie Huckaby, a devoted mother to eight who also managed to champion community, from her church to the city’s Board of Education. There are nods to Juanita Keen Cooper, Douglas McClure, and Edward Gillespie Benedict Miller III, all loved and mourned by their families still.

That spirit flows through Marsh’s work, an homage to her grandmother, the late Ella Nora Price. Price, who died in 2013, was a doting mother and grandmother, an educator, a bookworm and a pillar of community.

In the mixed-media piece, Marsh has fused her signature style with elements of Price’s life, from bits of fabric and round, flat beads to a portrait of Price herself. Beside a canvas, a mobile hangs gracefully down from the ceiling, inviting a viewer in. Amidst the sunflowers are beads, bits of bright fabric, and tiny, green toy soldiers, a nod to her whimsical side as a mom.

The toy soldiers, for instance, come from Price’s vast imagination—and her role as a lifelong educator to both her kids and children across the city. Price's daughter, Dannetta Holmes Wiggins, fondly recalled playing with those figurines as a child. After the children were finished with them, Price would assign the soldiers with their new duty: standing guard on her TV stand in a neat line.

Once they were up there, she warned her kids and grandkids to never disturb them.

Dannetta Holmes Wiggins: "It may sound funny, but it makes me want to dance."

That warmth and occasional whimsy extended beyond her children. Growing up on Day Street in the city’s Dwight neighborhood, Wiggins said, it was impossible to miss the six-foot-tall sunflowers in Price’s front yard, her pride and joy. As they rose, bursts of light from her garden, they brightened up the block.

Price was also an expert in sewing, making kufis and traditional clothes for the whole family.

“Every year our church would do a family directory and they would add your picture to it,” Wiggins remembered. “And so each year we would come and each year she would make a different set of African garbs … for us to wear.”

As Marsh worked, the piece came together through periodic bursts of energy. She worked across media, folding in a mix of acrylic paint, spray paint, paper, yarn, oil pastel, wood, and an assortment of found objects. Every single detail felt weighted, intentional, something between a tribute and a grief practice.

But it wasn't until she started creating the mobile that she said she experienced a different level of concentration, Marsh said. The inspiration behind the mobile came to her in a dream. It is “one of the very few pieces” she has an emotional connection towards, she said. When it came time to title the piece, she knew exactly what to do. The title—She Was My Home—just stuck.

“She was my home, you know?” Marsh said. “Whenever life would be life-ing I knew to return there to her. Now that I have become in a place of healing and accepting her death, it is something that I’m very grateful for. It is a space that I still think of as my home.”

Marsh added that there was a sense of healing not only in creating the piece, but also through the interview process, as her family got together to share different interpretations and memories of Price.

“It got emotional in a way I didn’t anticipate, for sure,” Marsh said. “I think it also provided the opportunity for me and my mom to actually connect about my grandmother because it’s not something that we really had talked about since she had passed.”

Celena and Valencia Campbell.

Amidst the melancholy and grief of losing loved ones, a sense of optimism and strength flowed throughout the exhibition Saturday, at a reception filled with music and making. It was as if a viewer could feel the abundance of love from spectators and artists alike—the peace of knowing that these legacies would long be cherished and remembered.

“This whole event is breathtaking and it may sound funny, but it makes me want to dance,” Wiggins said. “It’s giving me ‘Happy Feet’ vibes.”

Those vibes extended to viewers Celenca and Valencia Campbell, the first of whom is a tattoo client of Marsh’s. Saturday, the two wanted to show their support for the artist outside of the tattoo chair by coming to see her piece.

Despite not having a close bond with Marsh’s family members, the piece hit home for Celena, who said she could feel a strong familial connection through the work. She interpreted the piece through a lens of faith.

“I’ve been on my own since I was nine, but I’ve always been rooted in God,” she said. “Even though I didn’t have people that I was rooted in … he put things in us that required that we have human interaction and affection and protection.”

“I can appreciate it to see it in the physical [world], as in, she got to hug her grandmother,” she added. “I can’t hug my mother, but I get it, I love it.”