Music | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

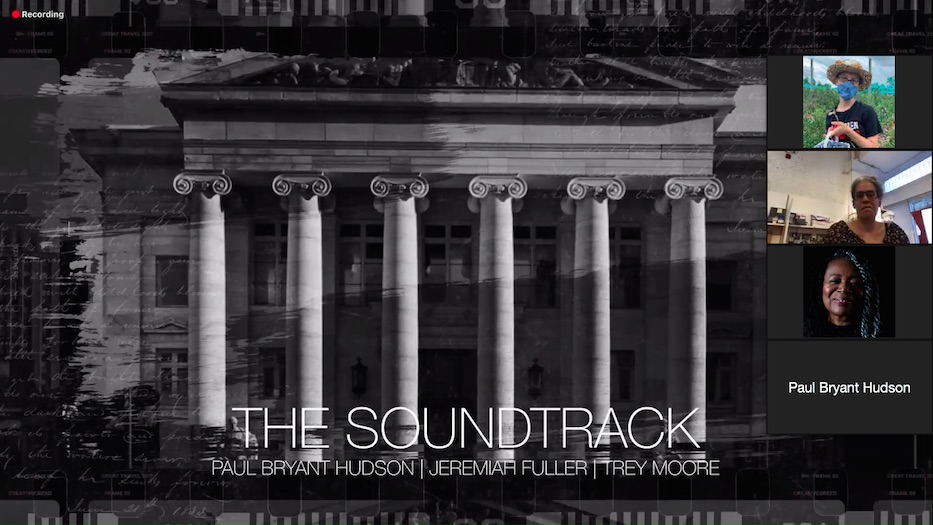

| Paul Bryant Hudson: “The three of us experienced these moments together. We experienced that thing in alignment because we’re from a lot of the same places. When it came time to create, when it came time to pivot … we knew that the ideas that we’ve thrown around a few months prior didn’t work anymore.” Screenshots from Zoom. |

Calls to defund the police crackled through the air, electric. It was May 2020, and thousands of New Haveners were standing on Union Avenue outside of the New Haven Police Department, facing a phalanx of officers in riot gear. Or maybe it was May 1970, and thousands of New Haveners were standing on Elm Street outside of the U.S. District Courthouse, demanding the freedom of Black Panther Party members Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins.

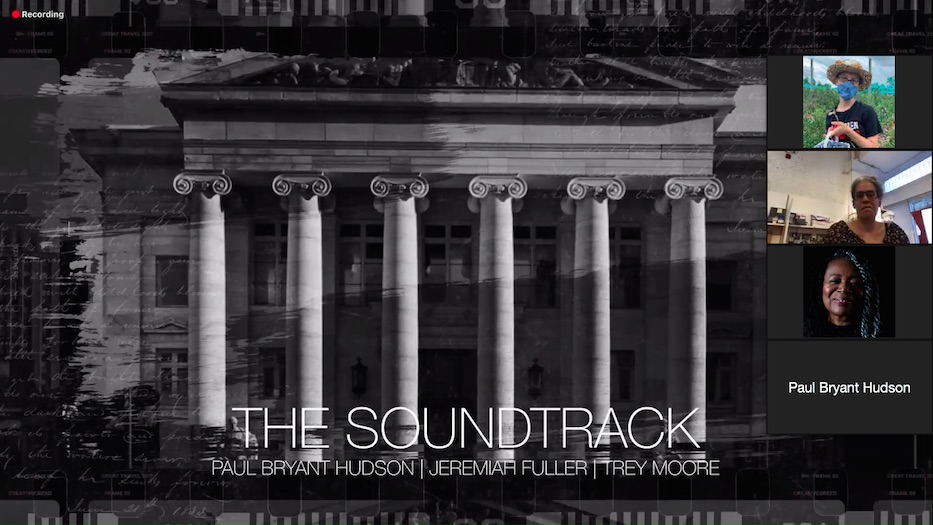

The work comes from Paul Bryant Hudson, Jeremiah Fuller and Trey Moore’s The Soundtrack, a five-part sound installation in Revolution On Trial: May Day and The People’s Art, New Haven’s Black Panthers at 50. The exhibition runs at Artspace New Haven through Oct. 17. Wednesday night, Hudson joined Co-Creating Effective Organizations (CEIO) co-founder Niyonu Spann for a conversation and listening session on Zoom.

The exhibition asks seven artists to reflect on the 1970 murder trial of Black Panther Party national chairman Bobby Seale, New Haven chapter founder Ericka Huggins, and seven other party members. While he appeared alone, he was quick to say that The Soundtrack is a collaboration with Fuller and Moore, who are also Hudson’s friends, bandmates, and themselves both musical dynamos in the city.

Wednesday, Hudson's story started not with the soundtrack but with his own musical roots, which he traced back to his great-grandmother, Syla A. Artis Branch. Born in 1917 in New Haven, Branch was a brilliant pianist, beloved across the city for her music and her warmth. For close to five decades, she served as the minister of music at Christian Tabernacle Baptist Church, which now sits in a squat brick building on the New Haven-Hamden border on Newhall Street.

The first time Hudson performed it was with her, he was just three years old. He was 17 when she passed away. When she died at 92 in 2009, she left almost a century of music in her wake. Smiling, Hudson recalled how she played up until the very end of her life, recording a double album of 50 songs on her 90th birthday.

“I grew up under her influence and under her covering almost, and I think that more than the music she taught me … there’s so much inheritance,” he said. “There’s so much that she just gave from her spirit to mine.”

“As I sort of discover and rediscover myself as an artist and a musician, I sort of lean on her,” he later added. “Her gifts, her creativity was so core to her person and her identity. Every day, I’m trying to trace that process and trying to trace that legacy.”

It was a legacy he looked to when Artspace came to him with the commission months ago, in a time before COVID-19 and the state-sanctioned murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Tony McDade. Initially, he, Moore, and Fuller talked about a soundtrack that would evoke “what a day in New Haven would have sounded like in the spring of 1970.”

Hudson is close with Moore and Fuller; he described their collaboration as continually organic, rather than careful and calculated. The three were excited as they traded ideas, soaked in music history and their own experiences in the city. They were particularly interested in what the city’s neighborhoods—neighborhoods where they later grew up—would have sounded like.

Then “the year turned,” he recalled. The coronavirus pandemic, which has since affected Black Americans at a rate three times higher than their white counterparts, hit New Haven and shut down the city. Amidst shutdowns, Hudson learned that in a Georgia suburb in February, two former police officers had murdered a Black man for going on a run.

For four months, those men slept in their own beds. Then, less than three weeks after they were arrested in May, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis. At a protest in New Haven at the end of the month, activists marching to defund the police were met by officers in riot gear, who later used pepper spray when organizers tried to enter the building and speak to the mayor inside. He came out only hours later, surrounded by police.

“The three of us experienced these moments together,” he said. “We experienced that thing in alignment because we’re from a lot of the same places. When it came time to create, when it came time to pivot … we knew that the ideas that we’ve thrown around a few months prior didn’t work anymore.”

He added that he felt grateful for the space to write, rewrite and create with Moore and Fuller. As the three worked, the soundtrack became a document that had as much emotional weight as it did musicological. Hudson recalled listening to Moore drop a hook, and knowing immediately that it was a message for the present soaked in the past.

In the finished work, five movements that run about 15 minutes, the three artists weave a through line from May 1970 through June 2020. In the first, a carpet of music unfurls to play Hudson in, his voice steady and filled to the brim. He situates the listener in the thick of protest—Friday we gathered in peace/but tragic responses from racist police—then unleashes a wail. It is all-encompassing, undulating where a listener thinks it might end.

New Haven is the work’s container, but doesn’t feel like a hard boundary. There are cacophonous explosions of sound followed by tinny, echoing keys that make time feel granular. There is audio from the May 31 protest in New Haven (" Thought it was important to make sure folks were aware that those are the literal sounds of our streets in crisis," Hudson later wrote in the Zoom comments) that drifts into audio from Fred Hampton, a leader in the Black Panther Party who was assassinated by law enforcement in Chicago 1969.

The soundtrack’s visual is a pulsing, grayscale portrait of the U.S. District Courthouse, a towering building that sits at the corner of Church and Elm Streets downtown. Wednesday, Hudson noted that for most Black residents in the city, the courthouse holds a significance and familiarity that it may not hold for their white peers. It is an uncomfortable inheritance—no matter one’s socioeconomic status, they are more likely to end up there if they are Black.

Wednesday, Spann asked Hudson what he made of community members who dismissed his music, and creative work more broadly, as “lesser activism.” She recalled how frustrated she felt in her own life when people suggested that music, which has long been the backbone to revolution, “that that’s not the real deal.”

“I’ll say this,” Hudson responded, mulling over his words until he found the right ones. “I don’t necessarily grapple with … I don’t necessarily feel the need to … I don’t feel like I don’t do enough. I feel like I do the things or I show up in the ways that feel closest to who I am. And as I do the action, I do it with a sense of love for the people, as Fred Hampton said in the fourth movement. And I feel like with that as a North Star, I can’t go wrong.”

“The thing I do grapple with is the price people pay for being on the front lines, and a deep desire to share in that pain,” he added. “I don’t pay a price for creating music. Music is delicious and palatable. And white folks have fed on and appreciated freedom music since the dawn of it. So much that they thought fit to put it in their hymnals."

Within that matrix, he added that his own process is in the midst of shifting. While capitalism may breed a system in which art is continually consumed—particularly Black art by white consumers—he’s trying to make more work for himself. He recalled a 45-second piece that he wrote recently, just a few days before the conversation. He was happy with it. He’s also okay—maybe even more than okay—if it remains his and his alone.

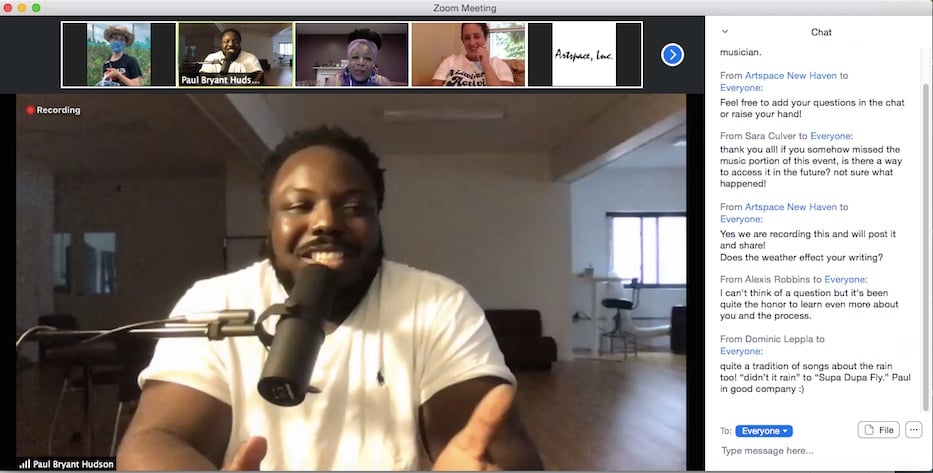

He has also expanded his creative and activist footprint as founder of The Kitchen, a creative coworking space by and for people of color. The space, from which he joined the broadcast on Wednesday, is located in the city’s East Rock neighborhood just above the Bradley Street Bicycle Co-Op. While it is still in the midst of renovations to become COVID-19 safe, it recently became home to “The Reconnection: Back In My Day,” a new narrative series hosted by Shamain McAllister.

“I have all these ideas for the space,” he said. “But the thing that I’m most excited about is letting the space be what they need it to be.”

Artspace New Haven has two more events associated with Revolution On Trial. The first, a video screening with artist Chloe Bass and research assistant Minh Vu, takes place Sept. 8 at 6 p.m. The second, a conversation between Angela Davis and Ericka Huggins, takes place Sept. 9 at 4 p.m. The exhibition runs through Oct. 17.