Ice The Beef | Kwadwo Adae | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Visual Arts | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

| Alex Callender’s History Constructs the House That Sometimes Holds Us is one of the works displayed in REVOLUTION ON TRIAL: May Day and The People’s Art, New Haven’s Black Panthers at 50 , running now at Artspace New Haven through Oct. 17. Arturo Pineda Photo. |

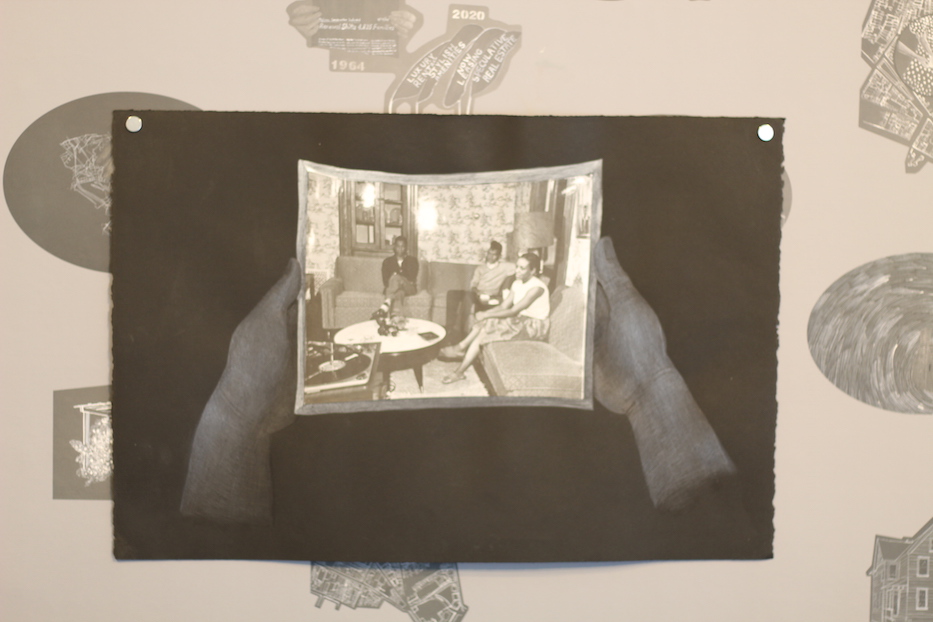

A Black fist punches through the side of a house. No, a set of Black arms is lifting the house. To the right, a Black woman stands in an incomplete or maybe ruined foundation of a house. A blueprint of New Haven and Wooster Square are visible to the side. Depictions of burning houses are scattered throughout the wallpaper. A 1964 news headline reads, “Renewal shifts 4,835 families.”

A 2020 advertisement nearby reads “Luxury rentals,” “Stylish Apartments,” and “Speculative Rentals.” In the center of the wallpaper hangs a picture of three Black people sitting in a living room. A record player playing in the corner. There is no more information on the group.

Alex Callender’s History Constructs the House That Sometimes Holds Us is one of the works displayed in REVOLUTION ON TRIAL: May Day and The People’s Art, New Haven’s Black Panthers at 50 , running now at Artspace New Haven through Oct. 17.

The exhibition was co-curated by La Tanya S. Autry and Sarah Fritchey in collaboration with living members from the New Haven Black Panther Party. George Edwards, a founding member of the party, was heavily involved in the process. The show originally centered on the 1970 May Day Trial, but quickly grew to become a larger exploration of Black New Haven’s organizing roots past and present.

It features seven artists and collectives, including artists Kwadwo Adae, Chloë Bass, Alex Callender, Melanie Crean, Ice the Beef, Paul Bryant Hudson, and Miguel Lucian. According to Artspace, the artists reflected on the 1970 murder trial of Black Panther Party (BPP) national chairman Bobby Seale, New Haven chapter founder Ericka Huggins, and seven other party members.

"While Seale and Huggins were ultimately acquitted of the murder of Panther member Alex Rackley, a suspected FBI informant, the 1970 case shook the city and underscored the deep inequities in the legal system and wider social structure," a release from the exhibition reads.

| An exhibition view of Kwadwo Adae and Miguel Lucian's work. Sarah Fritchey Photo. |

Lisa Dent, who took over as the organization’s executive director in May, said she intended for the show to capture the chronic nature of the Black Liberation movement and ground contemporary movements, such as, protests around the murder of George Floyd, in a larger conversation. Dent emphasized the importance of presenting a complex narrative through the lens of the oppressed rather than the oppressor.

“So many art exhibits focus on the oppressor and their perspective,” she said. “Instead, I wanted this exhibit to focus on the oppressed. I believe it does just that.”

Fritchey cited Emory Douglas, the prime minister of culture and “Artist of the Revolution” for the Black Panther Party, as a key figure in the curatorial vision for the show. Douglas’ illustrations of cops as pigs and Black people as empowered members revolting were instrumental in educating and organizing community members. He believed that photography as it existed was too steeped in the white gaze, explained Fritchey. Douglas said that “... art enlightens the party to continue its vigorous attack against the enemy, as well as educates the masses of Black people.”

In the finished show, each artist brings a unique perspective to multiple layers of history. Callender’s wallpaper installation, for instance, physically stitches together a history of a housing inequality from the 17th century to the present. The images, repeated with no end in sight, create an illusion of no beginning or end.

The artist’s thesis reveals itself: The housing crisis, a symptom of state violence, may have changed form through the decades but it is constantly repeating and reimagining itself. The raised fists and Black figures represent resistance and a fight for liberation that has its origins in the home.

Bass’, a hand that held and loved someone (Personal Choice #3), explicitly responded to the idea of a single perspective by focusing on a singular love story amidst the revolution.

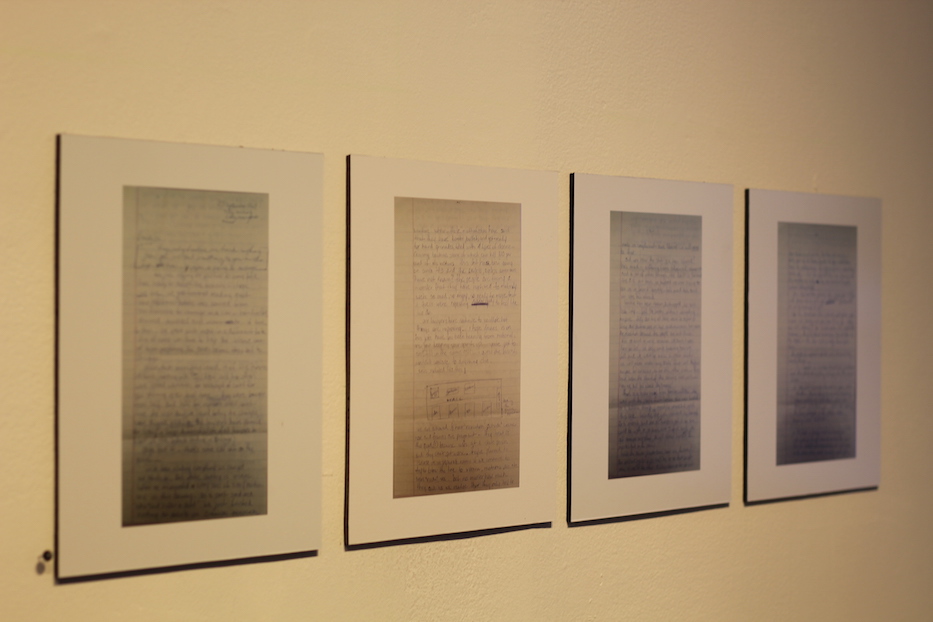

| Ericka Huggins' letters from prison. Arturo Pineda Photo. |

In the piece, the artist’s own narration plays over film footage of Ericka Huggins from the May Day 1970 protests on the New Haven Green. Scenes of Huggins laughing and smiling on the New Haven Green amidst protests are interspersed with scenes of bright skies. The video comments on the interwoven relationship between love, revolution, and sustainability.

“Make a revolution a place where we can stay,” the artist reads. “That’s what love is.”

“Remember, this is only one perspective. But remember too, that one perspective is all you have,” she later adds.

Bass’ work proposes that the revolution is a place to inhabit, rather than one to turn to only in moments of crisis. The revolution is sustained by small, mundane moments rather than moments of crisis. One perspective might seem limited and inconsequential, but if it is all a person can offer then it suddenly has tremendous value.

Adjacent to Bass’ video is an archive room filled with art from the Black Panther movement, maps of Black liberation, and video from the Stephanie Washington and Paul Witherspoon protests that unfolded across New Haven and Hamden last year. Most notable is the podcast, Revolution on Trial, co-produced by the Narrative Project and Artspace New Haven. The eight-part series features firsthand accounts by living Panthers, their lawyers and descendants, who reflected on the government’s efforts to end their movement.

The podcast was deliberate in centering women’s voices and examining gender roles within the party. It was hosted by Narrative Project Founder and Executive Director Mercy Quaye.

“Black women’s work was often discredited or not as valued in the party,” Dent said at a press preview on Friday. “I know I wanted their contributions to come forward.”

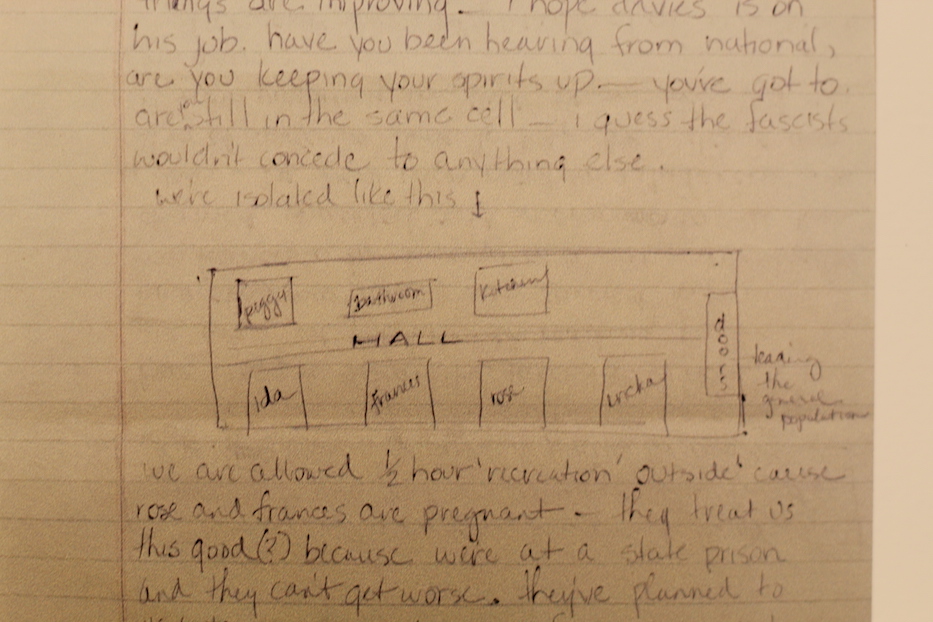

| Detail, Huggins’ letter from her time in the Janet S. York Correctional Institution in Niantic. Arturo Pineda Photo. |

Across the archive room, Huggins’ letters from her time in the Janet S. York Correctional Institution in Niantic hang directly next to Ice the Beef’s video, I Am You. Ice The Beef Vice President Ronisha Moore and members Priscilla Adopo, Catherine Wicks, Arianna Rivera, Elaine Lester and Nyrobi Vargas recite poems Huggins wrote during her detainment at the prison.

The recitation of the poems by these young Black women pays homage to Black women Panther members while acknowledging these women are the present iteration of the moment. It echoes loudly in New Haven, where queer Black women have been leading Black Lives Matter New Haven and People Against Police Brutality for the last several years.

Paul Bryant Hudson's Soundtrack, meanwhile, defines and reframes the May Day 1970 protests through sound. His work projects images of courthouses and news broadcasts, as instrumental music and sound bites from historical figures are overlaid. The soundtrack had six distinct movements: pain, inspiration, joy and solidarity, resistance, loss, and love.

The first movement, centering pain, reflects on Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” to communicate the familiar story of police brutality and its roots in anti-Black racism and oppression. The fourth movement, focused on resistance, includes an original percussive funk composition by musician Trey Moore, electric guitars, paired with soundbites from Fred Hampton. The strong and definitive notes mark the organized effort of Black resistance and solidarity building. The final movement, joy, is a love letter to Black ancestors and present and future activists.

“No, don’t settle in the Days to come - Things you won’t believe - Tears of Sorrow ain’t the wasted ones- Beloved, you’ll see- Things you won’t believe- Beloved, you’ll see.”

Despite the show’s focus on past events and elders, it also carves out space for future artists through the Artspace’s 20th Annual Summer Apprenticeship Program: Youth Justice Design Collaborative. The three week intensive allows high schools to work under the guidance of artist Daniel Pizarro. Pizarro modeled the curriculum after Black Panther Party’s independently funded Community News Service, which allowed the Panthers to share news about the Party on their own terms, just as Emory Douglas did.

The program was originally designed to teach techniques around zines, printmaking, and screen printing but the program was shifted online due to COVID-19. Instead, the program focused on teaching animated gifs and digital design skills. It was held digitally.

“The pandemic has made me rethink my practice and recalibrate,” Pizarro said. “I had to do the same both as an educator and artist.”

The switch to virtual teaching allowed him to reconsider the scope of the program and consider more forms of artistry. As a result, he added a performance piece at the end of the curriculum to push students to express themselves even more.

The performance centered on the potential reopening of schools, on which the state's government has continued to equivocate. Students critiqued the shortcomings of distance learning, the burden placed onto older students who are responsible for younger siblings, and many other factors which highlighted the trouble with distance learning as it stands.

Ultimately Pizarro believed the program’s mission was to give students the necessary tools to communicate their messages. Students produced work centered around Black Lives Matter, LGBTQIA+ movements, Indigenous rights, and more. All of the work is displayed both in print and animated GIFs.

“I wanted to teach students design skills so they can learn how to leverage their artist and design practice so it can serve community needs,” he said. “ The students were already there in terms of issues they cared about. I’m only giving them the tools”

Similar to the collaborative, many artists were forced to adapt their original visions in response to COVID-19, and found themselves also making work that spoke to the legacy of resistance and Black liberation. Melanie Crean’s untitled portraits, 9 women, work in progress was originally intended to be two massive paintings, responding to two New Haven Courthouse murals painted by Thomas Gilberg White in 1913.

White’s murals presented justice as being administered by white figures. Crean’s work aimed to directly challenge this notion, and consider justice administered by Black women. They intend to complete the work once COVID-19 restrictions are lifted.

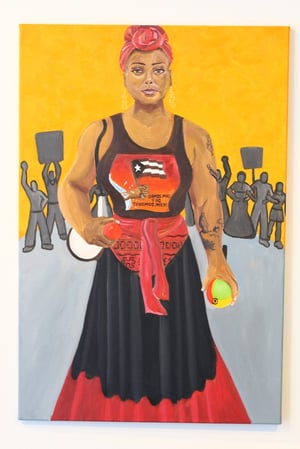

The show also resonates in New Haven, where protests have brought out thousands of people in the past three months. Kwadwo Adae’s Kerry, Addys, Norm, Sarah, Vanesa, and Ericka is a series of portraits depicting local activists Kerry Ellington, Addys Maria Castillo (pictured above), Norm Clement, Sarah Pimenta, and Vanesa Suarez dressed in their “protest armor.” Adae chose to paint the subjects instead of photographing them, to push back against protest imagery which is dominated by photography.

He also wanted to pay homage to the subjects through honorific portraitures, as was typically done for elite members of society. Ericka Huggins' portrait is not included in the series at the moment due to time restrictions caused by COVID-19. In an interview with Eric Rey last week, he spoke at length about how much he learned while speaking with her about her life and work.

Similarly Miguel Luciano’s piece, Shields / Escudos, was meant to have a performance aspect tied to it. The work, 10 shields made from decommissioned school buses in Puerto Rico, comments on the massive school shutdown in Puerto Rico due to debt crisis austerity programs. The choice to craft shields from the abandoned buses was both meant to repurpose the buses and provide armor for protests. Originally, an event had been planned for protestors to march down the streets of New York with the shields, but COVID-19 cancelled the event.

The show ultimately presents dozens of perspectives layered one upon another. This layering makes it clear that the liberation movement is a continuous conversation between past, present, and future members. Each perspective is necessary: freedom is a collective effort of love composed of thousands of relationships.

The exhibition will remain open through Oct. 17. A curator & artist talk will be held this Wednesday, July 29th, 5:30 p.m. via Zoom.