Arts & Culture | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

| Ala Ochumare, who is the co-founder of Black Lives Matter New Haven. "We can't have separation in this movement," she said Sunday. "I know we tired. I know we want to just fuck shit up, but that's not what we doing today. That's not what we doing today. It looks different here in New Haven. That's okay." Lucy Gellman Photos. |

It was after blocking the highway and marching to 1 Union Avenue that Ala Ochumare started to preach. Her call to arms: how to use an intersectional, sustainable movement to center Black lives, defund the police, and dismantle white supremacy.

“This isn't an admonishment,” she began as protesters stopped what they were doing to listen. “It's an opportunity. Follow us. Create the spaces. Create the change. We have to have one united voice.”

Ochumare is the co-founder of Black Lives Matter New Haven, which she began is 2014 with Sun Queen (Lauren Pittman), Dawnise Boulware, and Sy Fraiser. Her words reached hundreds of protesters Sunday afternoon, during a peaceful march and rally that began on Broadway Avenue, wove through downtown, and blocked Interstate 95 before going late into the afternoon and night at the New Haven Police Station. It continued there through midnight, as song, personal testimony, and call-and-response joined demands for an end to police brutality.

Police became violent late in the afternoon, donning full riot gear and using pepper spray after a few protesters tried to enter police headquarters. The headquarters at 1 Union Ave. is a public building. In a press release Sunday evening, Mayor Justin Elicker praised the department for showing “great restraint.”

The protest joins hundreds across the globe in mourning the murder of George Floyd, who was choked to death as a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck, as well as Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and most recently Tony McDade. In addition, activists in New Haven are calling for the firing of NHPD Officer Paul Vitale, who maced, tackled, and arrested a Black shopper at the city’s Walmart Wednesday night.

After initial confusion over who was organizing Sunday’s event—a post had gone up Saturday without attribution on social media—the protest was led by activist and LGBTQ+ advocate Ochumare and members of People Against Police Brutality and the Connecticut Bail Fund. Over 1,000 protesters were present at the height of it.

Ochumare, at the helm, commanded much of the protest with grace, sharing the megaphone with fellow organizers over the course of the day. Downtown, she gathered protesters by Campus Customs, speaking from the center of a human-formed circle.

While waiting for fellow members of Black Lives Matter New Haven, she urged white attendees to take their allyship not just through the march but also back into their neighborhoods, setting a tone she would hold throughout the day.

“I can’t watch another Black person die,” she said. “I refuse. And sometimes they still murdering us and we still walking and breathing. We still out here, creating. Building this whole fucking country. And they’re murdering us. I’m tired. I can’t even think no more.”

“We cannot let this fire die down,” she added.

Ochumare led the group through downtown, a call and response of “no justice/no peace!” and “ain’t no power like the power of the people ‘cause the power of the people don’t stop” filling the streets. When the group moved too fast, she slowed marchers.

When the crowd grew, she made sure that information traveled to stragglers in the back. When the group reached the on ramp to the highway, she kept going.

“We want our liberation!” she cried.

“Now!” the crowd cried back.

When she got the news that the Connecticut State Police had been called in, she and other Black Lives Matter New Haven activists ushered white people to the front, forming a human chain that lasted for hours. In a sort of activist ballet, she shared the megaphone with fellow activists including Ashleigh Huckebey, Amelia Sherwood, Sun Queen and others.

By the time she reached 1 Union Avenue—otherwise known as the headquarters of the New Haven Police Department—she had been on her feet and in the sun for over three hours.

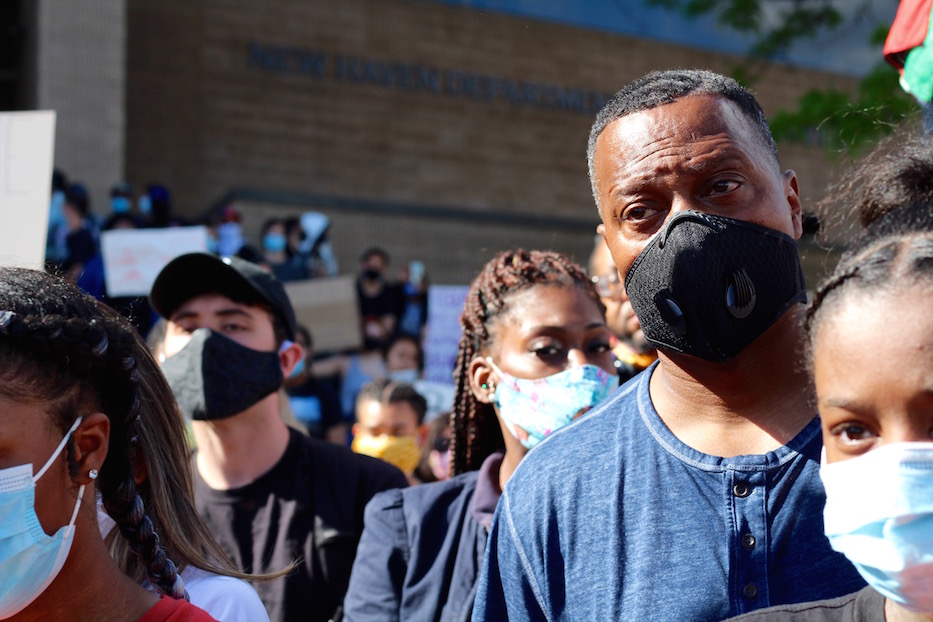

As protesters came down from the interstate and flooded Union Avenue, she joined speakers near the building’s entrance, separated from its front doors and lobby by a line, sometimes multiple officers deep, of about 50 police. Protesters, most shoulder to shoulder but in masks, packed the steps.

She traded on and off with Kerry Ellington, Jeannia Fu, and at one point the singer Thabisa Rich. An hour in, she watched as the crowd began to stir below. A few protesters shouted that they were ready to go back to the highway. Others just seemed to have stopped listening.

“Focus, focus, focus,” she said. “We are here for a reason. We are here because we are trying to create change. To demand it. That new way of being, it starts today.”

She explained that New Haven’s activist community—run almost exclusively by women of color—wasn’t sustainable for her in its current cycle. She described a manic movement that was based around cyclical protests, instead of sustained, diffused action. She urged attendees to build community day by day, pitching it as the only genuine way to have long-term divestment in the police.

Then midway through a sentence, she stopped and started down the building’s steps, cutting through the crowd as if she was floating.

“This is the beginning of a movement,” she said as she walked toward the center of Union Avenue, where a thicket of protesters gathered around her in a wide circle, trying to keep some distance from each other. Almost all of them whipped out their phones.

For the next 12 minutes, she held the street. With all eyes on her, she deconstructed the myth of Black-on-Black violence, noting that the police—as an outgrowth of white supremacy—"are the real murderers here.” She called on white allies, of which there were still hundreds present, to learn the language of anti-racism and deploy it with their peers.

She acknowledged the protesters that wanted to get back onto the highway, and urged them to look toward more sustainable action.

"I understand why y'all just want to be in these streets today,” she said. “I understand that shit. I want to be in these streets today too. That's why I'm out here. That's why we took over whoever's action this was, who wasn't moving transparent—because we doing this the Black way. We centering Black bodies. We centering Black people. Black and Brown bodies. But we have to create a sustainable movement, y'all. Not just today.”

Then she turned her attention to the movement building itself. She explained that she sees the divestment movement as one built between protests, when there is space to gather, call legislators, host discussions and build the correct vocabulary. She said she wants to see people—including and especially anti-racist white people—showing up to meetings, even if the COVID-19 pandemic means Zoom is the best forum for it.

She turned to those hoping to join, including protesters who had asked for a forum to speak later in the rally.

"Whoever got a megaphone, that's what we're listening to," she said. “Make sure that your message is not anti-Black. Make sure that your message is not anti-queer. And make sure that your message is for lives. Black lives.”

“Remember, this is the beginning of the movement in New Haven,” she added. “This is the beginning. We have to do this shit. This is a prime opportunity. It is election time, y'all.”

To find out more about Black Lives Matter New Haven, check out the group on Facebook.