Public art | Arts & Culture | Wooster Square | COVID-19

| Seven hours after the first protesters arrive, the statue's base moved. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

On one side of Wooster Square, hundreds of eyes watched a single spot. White sage sent wisps of smoke toward the sky. The air filled with snippets of Sam Cooke, Kendrick Lamar and Pete Seeger.

The base turned, slowly, and then almost a full 90 degrees. A larger-than life bronze of Christopher Columbus had begun its journey out of the park.

Wednesday, that moment marked the climax of a seven-hour standoff—and crash course in white supremacy—between Italian-American protesters, New Haven police, and New Haveners standing in solidarity with city orders to take down the statue of Christopher Columbus that has lived in the park for 128 years.

The moment comes a week and a half after city officials, several Italian-American societies, and Wooster Square neighbors formed a coalition calling for the removal of the statue, which was erected as a monument to Italian Americans in 1892. On June 17, the Parks Commission voted to officially approve the removal.

As of Tuesday, an injunction to reverse the city’s decision had been filed by the Italian-American Heritage Group. A ruling has not yet been issued; the statue has been taken down.

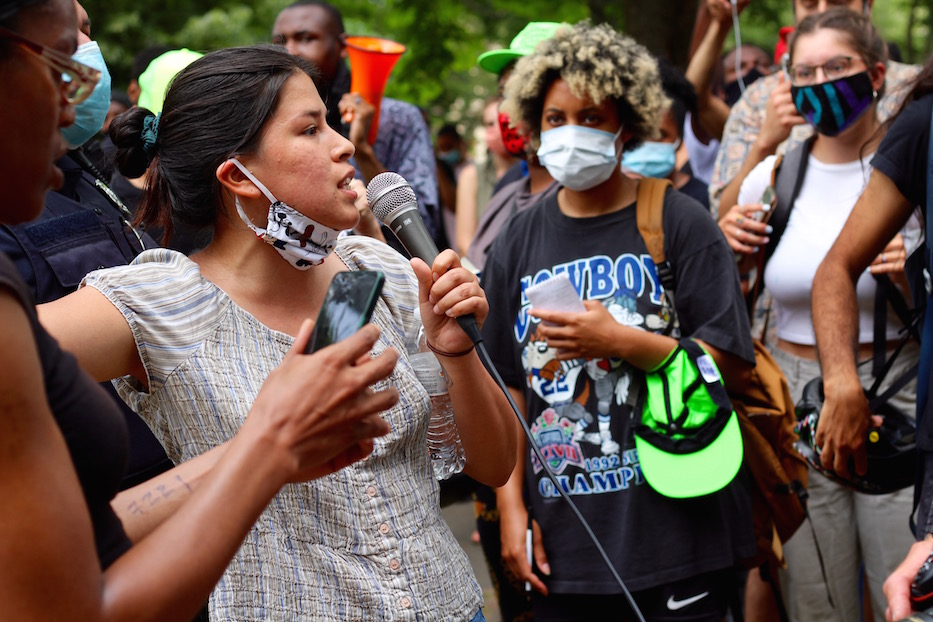

| Top: Community Organizer Vanesa Suarez as activists are told the statue may take time to come down. Bottom: 90-year-old Charlie Selarno leads protesters in "God Bless America." Selarno called the statue "part of my heritage." |

Most of the pro-Columbus protesters, who at points became physically violent, live in East Haven and all are white. Most pro-removal protesters live in New Haven and are Black, Indigenous, Latinx and white. Several city residents have been advocating for the statue’s removal for years, including as recently as last month. Monday, the city’s Board of Education also voted to change the name of Christopher Columbus Family Academy in Fair Haven.

The morning began at 5:30 a.m. with a small crowd of Italian-Americans gathered around the statue to mourn its removal. Several carried American flags and sported red, white and blue-patterned masks; others held hand-made signs that read “Where’s Rosa?” referring to Rosa DeLauro’s historical support of the statue (in a statement to the Arts Paper last week, she joined those calling for it to come down). Enough New York Yankees paraphernalia appeared to comprise a small team.

The protesters had come based on a tip that the city was removing the statue at 6 a.m. Elsewhere in the city, Mayor Justin Elicker was learning that the crane company that had been lined up had bailed at the 11th hour. Healy Crane Services, which is based in Bethel, stepped up but would not arrive for another four hours.

Around the periphery of the square, a few cops chatted and laughed with protesters. Almost none of them wore masks.

| Top: Officer Ralph Consiglio, who is assigned to the neighborhood. Bottom: East Havener David Gorman. |

East Havener David Gorman, who grew up in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood, said he viewed the removal as both a literal and symbolic loss of history. Gorman is Italian-American; his parents both came to the United States through Ellis Island when they were babies. Growing up in New Haven, he recalled hearing stories of Irish immigrants who called them “guineas,” a derogatory term that also referred to enslaved Africans.

For him, monuments and holidays dedicated to Columbus are a reminder of his own history. He also attributed the momentum around removing the statue to the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd, although activists have been pushing for the statue to come down for almost two decades.

“We came here just like everybody else came here, and I don’t think it’s fair,” he said. “I have a lot of Black friends. It was definitely wrong what the cops did. I've never even seen a move like that in my life and I hope I never see it again. So I understand the outrage over a thing like that. But this, I don't understand. I just can't wrap my head around it. They want to take the day away too. Where does it stop?”

He did not comment on the fact that, like Indigenous people who did not choose to be forced from their land, enslaved Africans were the only Americans not to choose to immigrate to the United States.

| Josephine Amarone: "My father’s not alive anymore, if he was here he would chain himself to this fence." |

Josephine Amarone, who grew up in Hamden, said she had come out to honor her family’s long history in Wooster Square. Dressed in bright, patterned scrubs for work, she talked animatedly with her back to the statue, leaning on the surrounding iron fence for support.

Growing up, Amarone’s history was tied intimately to Wooster Square. Her grandmother owned houses in the neighborhood. Her father grew up going to St. Michael’s Church; her brother attended the church’s nursery school. Like Gorman, she said she believes statues are coming down as a reactionary measure, rather than one that will result in long-term structural changes.

“My father’s not alive anymore, if he was here he would chain himself to this fence,” she said. “So I’m standing here in his place. This does nothing. This does nothing. If I’m an evil police officer, this coming down does nothing to change the evil in my heart. It will not eradicate it.”

Amarone suggested that if the city can take down a statue of Christopher Columbus, it should be pushing Yale University—named after Elihu Yale, who directly profited from slavery—to change its name as well. She added that she’s fine with an additional monument to Italian-American heritage, if it joins Columbus instead of replacing him.

“It’s a pretty big green. Put ‘em side by side, they could be paisans,” she said. “Right? You want Amerigo Vespucci over here? Put him over here, they could talk all day long. Get the maganet, they’ll have coffee. You cannot erase history. History is there for a reason. Good, bad or indifferent, it’s what we learn from.”

| Top: A sign that ULA mounted at the end of the ordeal, after Columbus had been taken down. Bottom: Peter and Janet Cianelli. |

Janet Cianelli, there with her husband Peter, called the city’s order “an atrocity.” Long before they were married, Peter grew up in Wooster Square, in a house his 98-year-old mother still lives in today. Both said they are proud of their Italian heritage, and consider Columbus a robust part of it. Peter blamed the Common Core curriculum for “trying to indoctrinate the children so that they forget our history.” The two are now longtime residents of East Haven.

“Today Columbus, tomorrow Jesus Christ,” Janet said. “This is America. Free. Christopher is standing here, not bothering anyone. 1492, he founded here. It’s our heritage. Next thing we know we’re gonna be taking down Martin Luther King statues. What’s it, a one-way street? Sorry.”

She also compared the statue’s removal to the removal of a Holocaust memorial. Six million Jews were killed in the Holocaust, alongside millions of people identified as LGBTQ+, disabled, and Roma. Columbus and his forces raped, murdered and enslaved millions of Taíno people.

At 6:49 a.m., a red truck sped past the park on Chapel Street, honking loudly. Protesters, thinking it was in defense of Columbus, cheered and pumped a few fists in the air. Then the driver stuck his face out the open window.

“He’s a slave driver, tear him down!” the driver yelled. As if pushed, the crowd gathered to sing “God Bless America” at the base of the statue.

| Rheta DeBenedet: It’s like taking a part away from us.” |

On the sidewalk nearby, 73-year-old Rheta DeBenedet chatted with a friend. DeBenedet grew up in Wooster Square, on nearby St. John Street. She watched as her family’s home was razed during urban renewal in the 1960s. At 19, she got married and moved to East Haven. She is still a parishioner at St. Michael’s Church and an active member of New Haven’s Santa Maria Maddalena society. As she spoke, a pendant of Mary Magdalene blinked out against her black shirt.

“It’s a symbol of our neighborhood,” she said. “It’s like taking a part away from us.”

Around the square, neighbors were waking up. A few stumbled out onto their porches; others walked their dogs at a safe distance from the statue. Others headed over to the park side of Chapel Street with cups of coffee and family members in tow. From a stereo by an open window, Luciano Pavarotti belted "Nessun dorma" over Academy Street.

| Top: Mathew Goude. Bottom: Eden Almasude. |

On a pre-work walk with a mason jar of coffee, psychiatry resident Eden Almasude watched the group with fascination. As a resident of Wooster Square, she’s been keeping track of the police cars parked outside the statue, often at all hours of the day and night. Now, she was watching people come to pay homage.

“This is like idol worship,” she said. “It’s ridiculous to spend so many city resources protecting something that is going to be taken down. It’s distressing that this is happening in the neighborhood—that so many people want to lift up and sacralize someone who has such a violent history. This is my neighborhood, and I want it to be a safe space.”

Matthew Goude, a nurse at Yale New Haven Hospital, stopped for a moment to watch the protesters on his way to work. Born and raised in Vermont, Goude grew up with a history of a virtuous, peaceful Columbus, whose sense of curiosity and intellect led him on a path to discovery. He was horrified when he learned more about Columbus after grade school. As a proud Italian himself—his mom’s side of the family hails from Sicily—he said he’s ready to watch the statue come down.

“We’ve Been Fighting For This For Years”

| Blair and Fidel. |

Around 9 a.m., Nate Blair and Los Fidel headed to the square, with signs and shirts denouncing white supremacy. As the first Columbus statue critics to arrive that day, they were not greeted kindly. Protesters soon became violent, hurling racial epithets at the two before also using their fists, pointing their canes and telling them, over and over, that they could not possibly be from New Haven.

First, a crowd rushed the two, trying to run them off with cries of "what are you doing here?" "they're fucking paid to be here" and "stop it, stop it." Someone who had separated the two urged their fellow pro-Columbus protesters to "call the cops, call the cops."

For a moment, it was a yelling match. Blair, who grew up on Mansfield Street and now lives in Wooster Square, urged attendees to calm down. He began to speak through the history of Italian assimilation to whiteness. His words were rooted in both American history and the history of race: Italians were able to effectively become white on American terms between the first and second quarter of the twentieth century.

"Did you know, Columbus Day is a celebration of Italian heritage," he began. "Right? So Columbus day is a celebration of when Italians were allowed to assimilate to white culture, right?"

"No, no, you're wrong," someone snapped back. "In 1890, 11 Italian immigrants were lynched. It was the biggest lynching in American history. That's why there's a Columbus day."

"So the reason why there's Columbus day is because the Knights of Columbus worked in part to make it a holiday, so that Italians could be considered white."

It was a snapping point for the group. They started yelling back. Someone screamed "learn your history!" He stood fairly still as a pro-Columbus protester ripped the sign out of his hands. Then someone threw coffee in Fidel’s face. Another came up behind Fidel and punched him.

The group broke into a run, following the two men of color (Blair is Black; Fidel is Ecuadorian and Puerto Rican and identifies as Native) around the square. A few tried to tackle Fidel; others shook until their neck muscles popped out and they were bellowing. The police around the square initially did not intervene; District One Officer Daophet Sangxayarath later worked with Fidel to file a police report.

Others tried to make conversation (watch more of that here), many screaming as they chronicled the number of Black people in the entertainment industry, pointed to Barack Obama’s presidency as proof that racism was over, and noted that they protest outside of Planned Parenthood “to save Black babies.”

At one point, a protester referred to people of color as “lowlives” living in “slum areas.” Fidel shook it off.

“We don’t want to erase history,” he said. “Just put him in a museum. We don’t like looking at that.”

Around them, New Haven activists and organizers had begun to enter the park, first at a trickle and then at a steady flow. Close to the statue, Norm Clement had started to bless the land, burning white sage leaves that sat in a bowl. A rattle bounced in his left hand.

“We’ve been fighting for this for years, not only here but across the country,” he said. “Columbus only represents to us murder, rape, and massacre, the enslavement of Indigenous people and the continued genocide that we have endured for over 500 years.”

| “Columbus only represents to us murder, rape, and massacre, the enslavement of Indigenous people and the continued genocide that we have endured for over 500 years.” |

For Clement, it is both a human rights issue and a personal one: he is a member of the Penobscot Nation, raised by a father who was not taught about his Native history after a white family adopted him out.

Clement himself did not know he was Native until he was 15 years old, and connected with an aunt who lives in Maine. Each year, he gathers with other Indigenous people on the National Day Of Mourning, which many Americans refer to as Thanksgiving.

“Once this is down, we gotta re-bless this ground,” he said. “The evil of Columbus should be wiped off Turtle Island, as we call it.”

As he blessed each side of land on which the statue sat, Italian-American protesters followed him around the space. One, wearing a green shirt pulled tight over his frame, called Clement a “fucking Indian."

Amarone, still leaning against the iron railing, began to lead those close to her in the Hail Mary and Lord’s Prayer, their voices rising over Clement as he offered his blessing. Thomas Cama, who is a trustee of the New Haven City Employees Retirement Fund (CERF) and later knelt on a walkway to prohibit the entry of the crane, spit at Clement.

| Top: Thomas Cama. Bottom: An Italian-American who has not yet learned that he is white. |

Of the pro-Columbus protesters who remained by 9:30, very few were wearing masks over their faces despite the threat of COVID-19. Of the activists who arrived, almost all of them were wearing masks. Ashleigh Huckabey, who has become a constant presence, encouraged fellow activists not to engage. She lit a bundle of incense that she waved back and forth as she spoke.

“I honestly just want to bring the energy,” she said, clearing the air around her. “The good energy. There’s a lot of heightened emotion here. A lot of people actually don’t know what they’re fighting for. And so, when you’re ignorant, you spew hate. When you educate yourself, your ego gets calmer. I’m just out here to calm everyone’s energy and calm everyone’s spirit.”

Huckabey—who is a lifelong New Havener, with deep roots in the city—hadn’t initially planned to come to the protest. Then she saw people of color being verbally and physically attacked in the place she calls home.

“I don’t like this being the representation of my community, of New Haven,” she said. “These are not the people that represent me. That represent the fight. That represent what people are really trying to do out here to spread love and spread change and spread positive energy, so that everyone’s included.”

Around her, pro-statue protesters continued to scream, muscles popping as they debated versions of history with Kharisma Redding and Fidel. Many threatened physical violence and attempted to remove activists from the area by running after them. A fleet of legal observers had appeared, their lime green hats dotting the space.

It was close to 10:45 a.m. when police separated pro- and anti-Columbus crowds. Top brass, dozens of whom had arrived—ushered Italian-Americans onto Chapel Street. Activists remained close to the statue. Somewhere close to the statue, Chief Otoniel Reyes argued with organizer Vanesa Suarez on what made someone an agitator.

The crane would not arrive for almost another hour.

Goodbye, Columbus

| Top: Miller at work. Bottom: Assistant Chief Renee Dominguez. |

In the time that it took the crane to arrive, the mood in the park lifted. What had started as a pro-Columbus protest became a half-rally, half-celebration with song, dance, intermittent prayer and cheering by those who wanted to see the statue go. Time—there were still some three hours before the statue was at last removed—seemed to become porous.

Celebrating Rosa Parks, Malik Jones, Mubarak Soulemane and others, activists led the group in round upon round of “What Side Are You On?” Using his own megaphone, Pastor Kelcy Steele, who leads Varick Memorial AME Zion Church on Dixwell Avenue, urged the group to view racism as a public health crisis.

| Top: What side are you on? Bottom: Justin Farmer. |

Hamden Town Council member Justin Farmer, who is running for State Senate, noted that he was horrified to learn that a plaque rededicating the statue had been placed as recently as 1992, the 500-year anniversary of Columbus’s maiden voyage.

"The fact that we're re-commemorating the fact that Columbus is a racist murderer—we all know that—that speaks volumes to what the current culture is," he said. He motioned to the growing number of police who had arrived over three hours, as attendees switched from predominately white to predominately Black and Brown.

The group was interrupted by the gentle purring of an engine: the crane and truck from the Department of Public Works had arrived. Police, on the other side of the square, removed a line of white protesters who stood in front of the vehicle, blocking its entrance to the park.

As activists watched it come in, they cheered and whipped out their phones. Several officers ushered them back off the grass and onto a walkway.

It kicked off over two hours of celebration, as some watched the anatomy of a toppling monument and others reconnecting with friends they hadn’t seen as frequently because of stay-at-home orders. Someone showed up with boxes of glazed donuts; another group brought hand sanitizer, cold water and bags of apples.

| Sun Queen/Lauren Pittman, who is one of the founders of Black Lives Matter New Haven. |

Art filled a small section of grass: Unidad Latina en Acción laid out hand-painted banners that they have been using in their call for a name change for years. Behind it, calls for anti-racism rang out, fists intermittently raised to the sky. When police announced that the process might take longer than expected, Redding asked the crowd if they were ready to go home and get camping equipment. She wasn't joking.

Out of nowhere, Thabisa Rich’s voice pierced the air. She lifted a black megaphone to her mouth and unleashed a Sam Cooke cover that has made its appearance on the steps of the New Haven and Hamden police departments and in the city’s streets.

“I was born by the river/In a little tent,” she belted. “Oh, and just like the river/I've been running ever since. But I knoooow, I know, a change is gonna come.”

When she had run through the cover, she kept singing, ad-libbing lyrics that urged parents to teach their children about racism, white supremacy, and the full history of Columbus.

| The singer-songwriter Thabisa Rich, who has become a fixture at protests in the last 18 months. |

The music became a steady stream: through a speaker, Kendrick flowed into Childish Gambino. Multiple times, Steam’s “Hey Hey Goodbye” echoed over the space, each with a slightly different cadence. As Miller fitted a hook onto a series of chains around the statue, Lolly Bee took the mic. She led attendees in an Indigenous chant that “a sister” had taught her before Wednesday.

“For me, this represents the symbolic end of colonialism, the end of white supremacy,” she said. “It felt like the ancestors were asking for it.”

Feet away, conservator Francis Miller fixed a series of ropes and chains around the statue, in a fashion some onlookers remarked reminded them of a public lynching. The process, which included re-working the crane to account for the statue’s base, took over two hours.

At the end, Columbus rested on a truck, and was escorted out of the square. The court over which he presided for 128 years, looking down at a small globe in his hands, had turned into an empty base. The iron fence had been decorated with signs from ULA and Black Lives Matter New Haven. Crushed flowers, which had been there before the morning's events, sat pressed in the dirt.

In a press release after the removal of the statue, Mayor Justin Elicker thanked the community leaders who have remained steadfast that the statue should no longer be in Wooster Square.

“I know that there are some people who strongly disagree with the decision to remove the statute,” he wrote in a press release. “People have the right to protest and express their opinions peacefully. We will work collaboratively to ensure we honor New Haven’s Italian Heritage and immigrant history. I look forward to the many community conversations surrounding what we would like to see replace the statue of Christopher Columbus, and how we can highlight other cultural icons for the many Italian-Americans that have made New Haven their home."

To read more about the steps that came before the statue's removal, click here.