Culture & Community | Hamden | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | ConnCORP | Arts & Anti-racism

Top: In focus are two pieces from photographer Liah Sinquefield, who has been documenting everyday sacred spaces for the past four years. To the left are pieces in Aisha Nailah's "Afstral Plane" series. Lucy Gellman Photos; all work by the artists. Bottom: Work by Ramirez.

It’s the way that Selene Fleming looks out at the camera, quiet and devastated, that pulls a viewer in. Her mouth is a fleshy, solid line, lips just short of pursed. Her eyes are wet and red at the edges. Somewhere beyond the lens, words echo over the room, their weight heavy and solid. Even from feet away, it’s possible to feel the exhaustion of the moment.

Fleming—and her daughter, the photographer Liah Sinquefield—is now a part of Gather, the first exhibition to grace the Orchid Gallery at the LAB at ConnCORP. A collaboration between ConnCORP (Connecticut Community Outreach Revitalization Program) and the bldg fund, the show brings together the work of eight Connecticut artists, telling a story of family, creative community, and lived history one work at a time.

Artists include Kulimushi Barongozi, Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, Aisha Nailah, Moshopefoluwa “MO” Olagunju, Daniel “Silencio” Ramirez, Liah Sinquefield, Arvia Walker and Yves Wilson. At turns stunning, visually arresting, and heart-rending, it is curated by nico w. okoro, who runs bldg fund with her partner, Malik D. L. Okoro. It is on view for the next three months at 496 Newhall St. in Hamden.

nico w. okoro, curator of the exhibition.

“We want to build a very intentional space,” okoro said at an opening reception last week, noting the gallery’s mission to uplift Black and Brown artists. “What even does it mean to have a gallery and a space that feels welcoming? We want to make space for everyone who wants to be a part of this thing.”

The gallery, which is supported by the NewAlliance Foundation, stems from a shared love for and deep belief in artists of color, who have historically been manipulated, micromanaged, and pushed to the margins at New Haven’s white-led, legacy arts institutions. Thursday, ConnCORP CEO Erik Clemons said the gallery fulfills a three-pronged mission: to uplift voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) artists, to show ConnCORP’s multidimensionality, and to highlight okoro’s curatorial footprint.

It also builds on ConnCORP’s growing commitment to the arts. Last year, public artist Kwadwo Adae completed a mural celebrating Black entrepreneurs in the LAB’s first-floor cafe. Last summer, the building was also home to the Sixth Dimension, an Afrofuturist festival that stretched across New Haven and Hamden. In its $146 million plan for ConnCAT Place on Dixwell, ConnCORP has made space for a two-story performing arts center.

MO's work is some of the first to greet viewers as they enter the gallery.

In the new gallery—which has transformed a quiet hallway—the walls sing with artwork, from Barongozi’s bright, large-scale canvases to Ramirez’ experiments with brilliant, marbled cyanotype on cloth and layered printmaking. In so doing, all of the pieces bring a sort of nuance to the exhibition’s title, asking a viewer to think about both how and what these artists gather in their own lives, and what one can learn from looking closely at the work.

Close to the hallway’s entrance, MO’s large-scale canvases double as a sort of invitation, drawing a person through the door frame and into the hallway where the gallery now exists. In one, a figure cups their partner’s cheek, so tender that the warmth of their hand nearly comes off the canvas. Both close their eyes, locked in a sweet embrace.

Around them, paint is piled thickly in greens, oranges and blues, and it feels possible to get lost in its swirl. A spray of red flowers bloom above them, and for a moment, it is as though these lovers have willed spring all on their own.

“Moshopefoluwa ‘MO’ Olagunju and Yves Wilson consider gathering a radical act, one that challenges conventional power dynamics and dominant historical narratives by putting forth what Olagunju describes as ‘unconventional’ representations of the body,” okoro writes in an accompanying text. “Here, to gather is to summon intuitive ancestral and diasporic wisdom in assembling symbols that speak louder than words in telling our stories.”

Walker: “I’m processing my grief through creating.”

That sense of art that probes, bends, and stretches the very definition of “gather” extends to other works in the show, creating a through line for the eight artists. Across the hall from MO’s work, a quartet of Walker’s photographs mark her journey from picturing organizing to family, two different sides of what it means to document one’s history with grace and urgency.

The images show members of her family, some haloed in gold that makes them look saint-like, beatific. In one of the photographs, her grandmother looks out at the camera, arms extended and back relaxed as she meets the viewer’s eyes. In another, Walker has taken a portrait of her grandfather, who passed away suddenly in 2019. He smiles, easy, freezing the moment in which he is still living.

“I’m processing my grief through creating,” Walker said. During her grandfather’s life, he encouraged her to practice her photography on him. The images, many of which she recently revisited for the first time in years, now feel like ancestor reverence. “This is healing work and spiritual work.”

It’s her two portraits of hands meanwhile—weathered, battered and beloved by time, working with that warm muscle memory that only elders have—that may stop a viewer in their tracks. At the right, a large pair of hands holds a smaller, still-evolving pair, the tenderness nearly radiating out of the frame. Both seem to glow, such that there is light everywhere even in a black and white print. Beside it, her grandfather’s hands rest atop each other, etched with time.

Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez.

That eye toward family and healing continues in new work from Gonzalez Hernandez, a lifelong New Havener who birthed the community of practice Fair Side in the spring of last year. In her work to decouple artmaking from institutions (and often the white, capitalist expectations that follow), Gonzalez Hernandez has centered both healing and experiment, and harnesses both in her silver gelatin prints for the gallery space.

In the first, titled “Mamí,” Gonzalez Hernandez has taken an old photo of her mother, lying on a Mexican blanket, and exposed the negative on paper, rubbing the developer with her hand to create a smudged, blurry effect. Beneath it, the image “Born In Blood And Fire,” has used the same technique, creating an image that appears to bend time and space.

“I was playing with the idea of control and lack of control,” she said. When Gonzalez Hernandez’ family came to the United States from Mexico, they were expected to assimilate. They left customs behind. They lost their Indigenous language. They parted with family and land that had been part of their origin story. Gonzalez Hernandez thinks about the echoes of that in her own work.

“In these photographs, I’m working through these intense feelings” associated with that story of displacement, migration, and finding or re-finding home, she explained, praising okoro for giving her the space to experiment and ask new, still-embryonic questions in her work. “I like to re-make the image. Reclaim the image.”

Sinquefield and her mother, Selene Fleming.

So too in two photographs from Sinquefield, dedicated to the matriarchs in her family. In the first, her mother, Selene Fleming, looks out at the camera, utterly exhausted by the day—or maybe it is the week, the month, the year—she has had. In the world of the image, it is November 2020, and she has just learned that her friend Sharon Clemons is in the hospital. As the camera clicks, her face is a prayer that too many of us know some version of: so tired and so scared—and so not in control—of what may be to come.

In a print beside her, a naked, sun-speckled breast with a patch of gauze feels like it’s a conversation piece. And it is: Sinquefield is showing the viewer a glimpse into her mother’s battle with breast cancer, a disease that claimed her grandmother's life in the form of stage IV lung cancer earlier this year. When she passed away in January, Sinquefield wanted a way to both memorialize her and think more deeply about the moment.

“I wanted to explore what it means to be the only child of another only child,” she said. “They’re always telling me, ‘You’re staying strong for each other.’ This shows vulnerability.”

Across from them, a vibrant print from the photographer’s trip to South Africa shows Sinquefield’s range and nuance, her ability for capturing a moment whether it is in New Haven, or half a world away.

Aisha Nailah, whose work is usually more abstract.

For other artists in the show, the work is familial on an ancestral, spiritual level that goes generations deep and is still very much unfolding. In her series “Afstral Plane,” Bridgeport-based artist Aisha Nailah has presented a grid of several small images and one large one, all meant to represent different “original beings.” After starting the series in 2019, she said, she hopes to reach 100 works (she is currently closer to a dozen, only one of which is a larger canvas),

In the pieces, she looks to core identities—teacher, mother, father, healer—and paints each, using gold and brown earth tones that made the pieces feel elemental, organic. The works differ from much of her oeuvre, which is otherwise almost entirely abstract. At last week’s opening reception, she had high praise for both the gallery and the opportunity to show a different side of her work.

“It’s so important!” she said, noting the loss of Black neighborhoods that once created self-sustaining business and art. “There are not many spaces dedicated to artists of color, Black artists. Here, they [okoro, Clemons] get what you’re doing.”

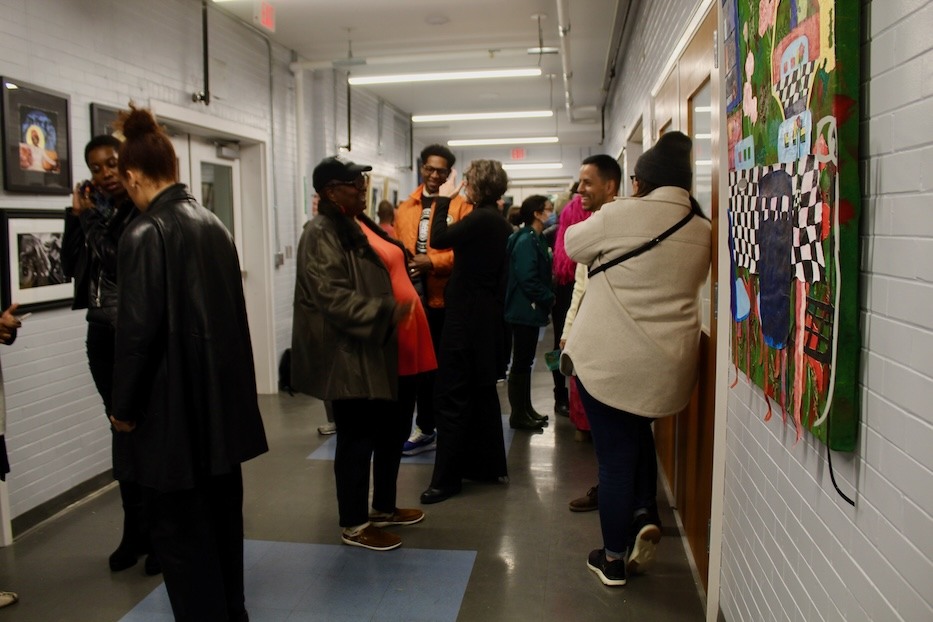

Attendees gather at Gather's opening reception.

Together, these works lend another layer to Gather: they invite viewers to linger, to catch up with each other, to assemble and to introspect among the pieces. Indeed, to gather both thoughts and people at a time when the world is incredibly polarized. It’s here that the show’s collective power lies: okoro trusts her viewers to make that narrative leap, and the space, if unconventional, gives them the time to linger if they want to.

That’s true going forward, she added at the opening last week. Currently, she doesn’t have a closing date in mind for Gather, but said that the gallery will likely rotate three more times this year. After selecting from 30 submissions, she said, she’s deeply aware of how much talent is in the area, and excited to continue working with artists for exhibitions to come.

“In its many forms, the act of gathering is about drawing in and holding together,” okoro writes of the show in an accompanying pamphlet. “Like the tie that binds, this exhibition aspires to keep us together, purposefully, through ongoing self-reflection and community discourse.”

Orchid Gallery is located on the first floor of the LAB at ConnCORP, 496 Newhall St. in Hamden. The building is open 9 a.m. through 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.