Books | Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Westville | Arts & Anti-racism

Ainissa Ramirez at Mitchell Library Monday night. Raquel Burgess Photos.

Ainissa Ramirez’ new book, The Alchemy of Us, came to her by accident. One winter evening after a particularly trying day at work, she attended her glass blowing class. Her frustration at her difficult day brought a little more vigor to her glass blowing than was recommended—and in the end, her hot glass vase fell to the floor.

“Hot glass can burn your skin. Hot glass can burn a hole in your shoe … don’t ask me how I know that,” she said Monday night to a room of 20 people at the Mitchell Branch Library in Westville. She realized that while she had been shaping the glass, the glass had been shaping her. It had distracted her from a bad day, increased her appreciation of materials, and ultimately changed her grumpy mood into gratitude for being alive.

Ramirez brought that anecdote—and several others—to Mitchell during an author talk and signing for The Alchemy of Us. After winning the 2021 Connecticut Book Award for nonfiction, she returned to the library for one of her first in-person events since the start of the pandemic last year. It is a special place for her: she wrote much of the book inside the building.

Beneath bright, incandescent lights, Ramirez looked to the importance of storytelling in her process, which separates the book from its more jargony, hard-to-understand counterparts. In The Alchemy of Us, she examines eight different inventions—clocks, steel rails, copper communication cables, photographic film, light bulbs, hard disks, scientific labware, and silicon chips—and the processes by which they changed the experience of being human. On Monday, her audience listened attentively, offering tiny grunts of appreciation and occasional laughter in response to Ramirez’ witty conversational style.

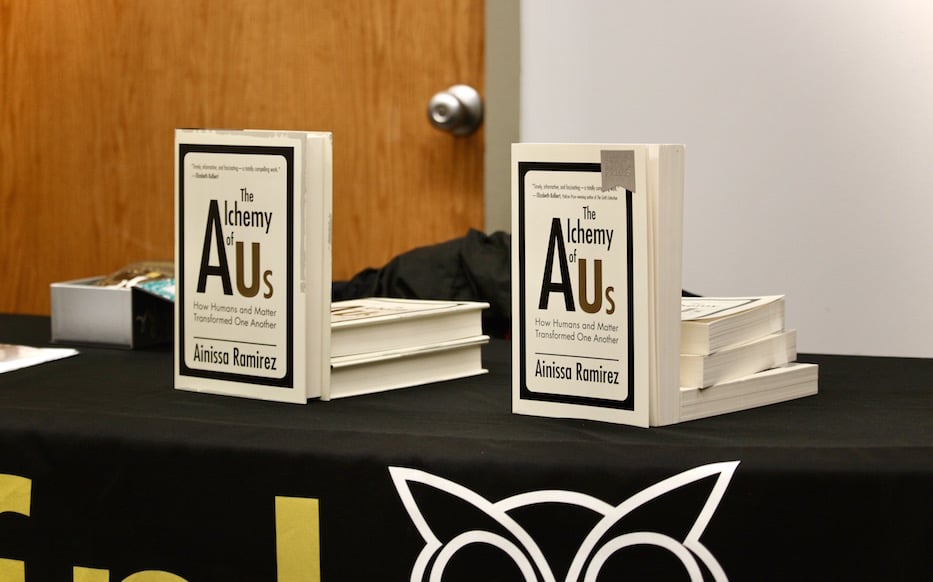

Copies of The Alchemy of Us. The cover of the book, which Ramirez wrote large chunks of at Mitchell, was designed by Westvillian George Corsillo. Raquel Burgess Photos.

Born into a working-class family in New Jersey, Ramirez became interested in science through watching the television show 3-2-1 Contact, in which she observed a young Black girl asking questions about science. As she writes in the book, “When I saw her using her brain, I saw my reflection.” Her own connection to scientific story led her to complete her undergraduate degree at Brown University, then her graduate and doctoral work at Stanford.

Her belief in sharing that story brought her into the New Haven community. As an associate professor of materials engineering at Yale University, she created several patented inventions. The project she was most excited for, however, was teaching children about science during Yale’s “Science Saturdays,” a community program that she led for years. After a decade, she left Yale in 2012 to teach others about science and become a self-proclaimed ‘science evangelist’.

“I was a teacher, not a lecturer,” she said Monday. “Lecturers want to show you how smart they are. Teachers want to show you how smart you are.”

Since then, she has written several books, including Newton’s Football, and Save Our Science, and a book about inspiring young children to engage in science. She has also written for publications such as Time, Scientific American, the American Scientist, Forbes and the New Haven Independent.

Ramirez signs a copy of her book for Jamie, a high school student at New Haven Academy.

While telling her personal story, Ramirez also captivated her audience with the narratives behind historical inventions that shaped human culture. Her approach, she said, is a reflection of her belief in the power of stories to communicate science.

“Stories are like conveyer belts”, she said. “You can keep sticking information on them and it will keep on going and people won’t realize they are learning.”

In order to illustrate how technology shaped (and continues to shape) human culture, Ramirez began her talk with an anecdote about Ruth Bellville, the women who sold time. In early twentieth century England, knowing the exact time required access to astronomical observations and calculations. Therefore, someone who needed to know the time would have to travel to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, in order to observe it.

Obviously, this was very inconvenient. So, Ruth Belleville brought time to her customers by traveling to the Royal Observatory once a week and recording the time on her relatively advanced pocket watch. She would then sell the time to her customers—local businesses, post offices, rail road stations, and the like—in order to make a living.

As knowing the time became more and more accessible with the advent of better and better clocks, Ramirez explained, humans began to live more strictly by its constraints. Fast forward to today, when you might feel more than slightly panicked at the thought of being unable to access your Google Calendar for even one day. The invention of timekeeping drastically changed how humans live, work, sleep, and play.

Ramirez moved on to describe how there can be unintended consequences of technology. Building on her discussion of the effects of timekeeping, she explained how the invention of the lightbulb increased working hours and unpaired humans from their reliability on the cycle of the sun.

Though there were certainly a vast number of benefits of this invention—our society would be unrecognizable without it today—Ramirez described how the invention of the lightbulb has had unintended health effects through disrupting bodies’ natural “growth” and “repair” stages. Since we now live under blue light for a solid 16 to 18 hours a day, our bodies spend less time in the repair phase. Scientific research suggests that blue light may be related to the risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers.

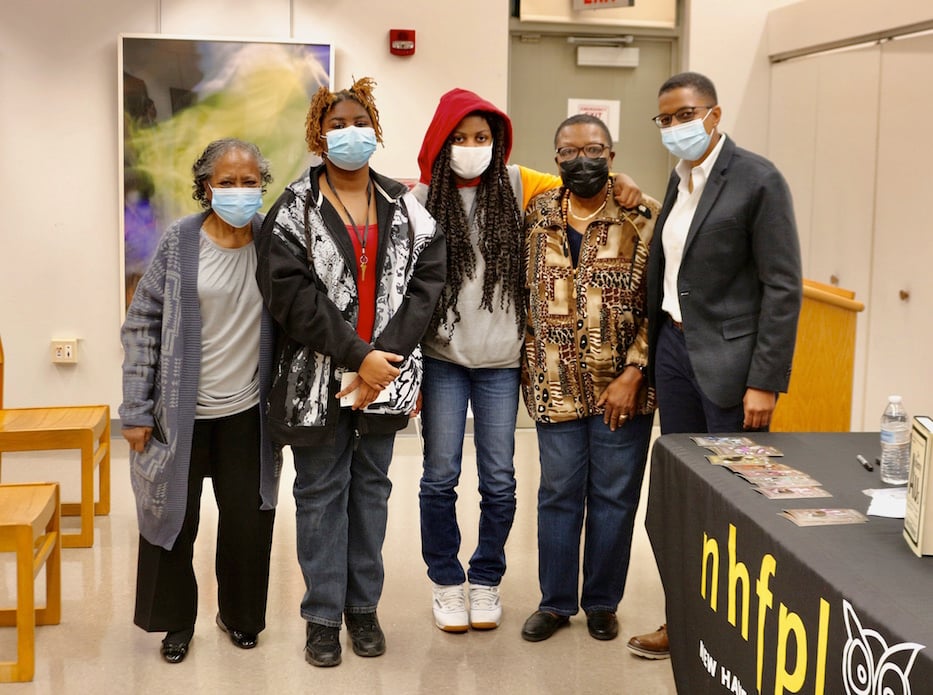

Ramirez poses for a photo after her talk with (left to right), Dr. Sheila Stiles, a research geneticist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Kayley, a middle-school student at Brennan Rogers Magnet School, Jamie, a high school student at the New Haven Academy, and Lensley Gay, a Site Coordinator at the New Haven Public Schools Family Resource Center. Artist Kim Weston's work is pictured in the background. Raquel Burgess Photos.

Ramirez’ final story revealed how technology is not neutral—it can be used for good, and it can be used for evil. She described the legacy of Caroline Hunter, a Black woman who worked as a research bench chemist for Polaroid Corporation in the 1970s. Hunter loved her job at Polaroid until she discovered that Polaroid was producing photos of Black South Africans that were a key component of their identification Pass Books—documents that Black South Africans were required to carry around that described to police where they could go and when they could go there during apartheid in South Africa.

She formed the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement in order to get Polaroid to stop their involvement in producing the Pass Books. Though it took seven years and she ultimately lost her job, Hunter and the Polaroid Revolutionary Activists succeeded in getting Polaroid to pull out of apartheid South Africa.

With this, Ramirez delivered a few more crucial lessons to her enraptured audience.

“We must make sure technology is serving all of humanity,” she said. “We cannot simply embrace technology. We must think about it and critique it.”

She lamented about how this belief flies in the face of the current tech industry’s mantra, which is to “fail fast, fail often.” Instead, Ramirez said, “We need to think about how the technology will live in this world.”

Ultimately, Ramirez said she hopes that her book will give people the agency to ask questions about science. She thinks that the current way of teaching science, which she believes is overly focused on facts, grades, and multiple-choice questions, is underserving people. By giving people the agency to ask questions about the ideas in her book, she hopes they will begin to feel comfortable asking questions about larger societal issues such as climate change and artificial intelligence.

With this, Ramirez said, we can use technology to transcend our conditions and create a better society for all.

Learn more about Ramirez' work and The Alchemy of Us at her website.