Beaver Hills | Books | Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

Ainissa Ramirez. Bruce Fizzell Photo.

A woman walks into a horologist's shop and pulls a pocket watch from her purse. It ticks, soft and steady as a tiny heartbeat. In the shop, other watches tick back at a whisper. A clock stands at attention, waiting for a judgement from the woman. Neither she nor the watchmaker know how deeply they are molding the course of history—and not specifically for the better.

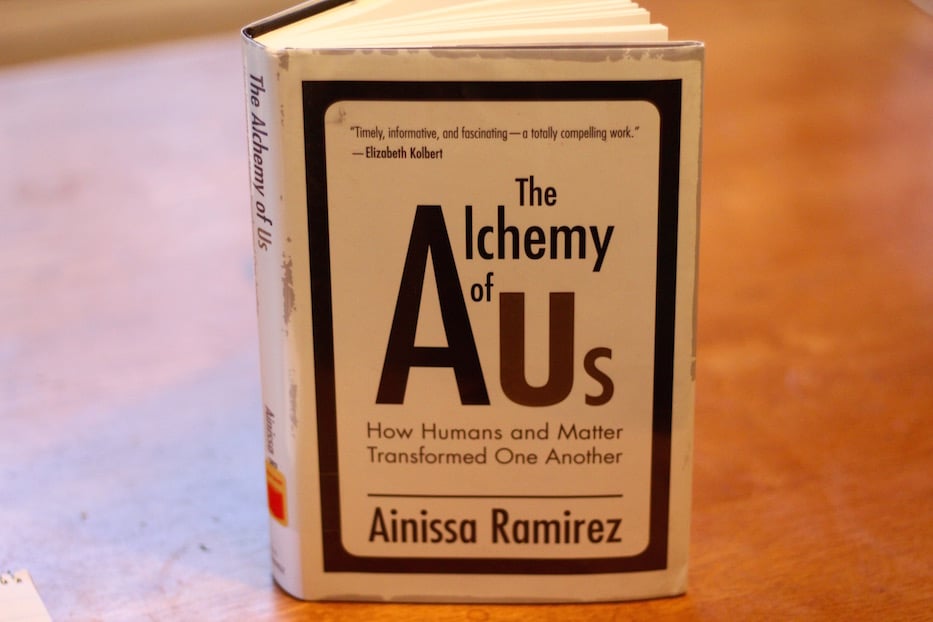

So unfolds The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another, a feat of both science and storytelling from New Haven author Ainissa Ramirez. Last month, the book was nominated for an L.A. Times Book Prize as a finalist in science and technology. A virtual ceremony is scheduled for April 16. It is published by The MIT Press and available for purchase here.

"I was trying to figure out how to get science to people," said Ramirez, who lives in the city’s Beaver Hills neighborhood. "I called myself a 'science evangelist.' I tried podcasting. I tried a tour. With a book, you’re able to provide more nuance. I wanted that to be the beginning of a conversation. Like, let me share with you this story that you didn’t know before, and let's talk about it. That's what I wanted."

Written over four and a half years, The Alchemy of Us tells the story of how people shaped technology, and how technology shaped them back. Guided by quotes from Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison—both alchemists in a way, although they did not always receive that recognition in their lifetimes—Ramirez tackles watches and clocks, the railroad industry, advances in photography and telephone communication, the rise of computers and more to contextualize our modern world. In her universe, these are not just inventions but also interventions, with capacity for good and for evil.

Ramirez uses science to understand, explore, and also challenge a narrative of forward progress, as well as the notion that innovators are overwhelmingly white and male. From the moment she opens on the story of Ruth Belville, also known as the “Greenwich Time Lady,” she probes technology and its discontents from the perspective of someone who has been relegated to its margins too many times. She succeeds wildly, with a narrative flair that leaves her reader excited to learn more about how and why things work (or as she said to this science-allergic reporter, “I wrote this book for you.”)

Belville, for instance, was a woman in twentieth-century England who “was in the unusual business of selling time” with her trusty pocket watch, affectionately named Arnold. As the story unfolds, Ramirez gives readers a bird’s eye view onto material history, painting a portrait of her that makes her feel wholly human. While Belville lived over 100 years ago, Ramirez writes as though she could be the realtor or clock seller or well-coiffed gadget peddler down the block. As she chronicles Belville's journey through the city, readers may see themselves reflected in her customers, who wish to literally keep and capture time.

The chapter is and isn’t a story about Belville, though: Ramirez jumps from her practice of telling time to the history of humans before and after clocks, teasing out how these precise, man-made objects changed human behavior. She looks into sleep, exploring how clocks could have disrupted something so fundamental to the act of living. She marvels at people who have found a way to warp and bend time, placing Albert Einstein and Louis Armstrong comfortably in each other’s company.

The book's cover was designed by New Haven artist George Corsillo. Lucy Gellman Photo.

In her eight chapters, each subhead is a stepping stone, yoking inventor and invention with cultural and material history. Ramirez is, perhaps, gobsmacked by the material world, but she is also keenly aware of the havoc that it has wreaked on the natural one and its inhabitants. Readers may know about the intimate tie between railroads and the economy, for instance, but can they connect molten steel with Christmas, nineteenth-century gift-giving, and a legacy of excess in the United States?

Maybe they have heard of the photographer George Eastman, but what of the Reverend Hannibal Goodman, a preacher whose quest for a patent may have been stymied by his long windedness at the pulpit? Have they considered the way white supremacy was baked into early photographic practices? Or that the blue-white light from an iPhone that may be affecting their lifespan?

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of such examples packed between the book’s covers. With each page, Ramirez demystifies and distills the world’s industrial building blocks, leaving readers more prepared to understand the place they so temporarily occupy. Chapters, which are richly illustrated and followed by an annotated bibliography, reflect a deep, wonderfully dorky dive into history that becomes as timely as it is philosophical.

In her chapter “See,” for instance, she follows the phenomenon of dwindling fireflies all the way back to nineteenth-century Connecticut, where inventor Thomas Edison (a name that readers are likely familiar with) entered the Ansonia studio of metals manufacturer William Wallace (a name that they may be less familiar with) and had a realization about light that changed the course of illumination. Ramirez puts a reader in a room with Edison and Wallace, soars forward to present-day light disruption, folds in poetry and fellow inventors, and circles back to fireflies.

In this sense, The Alchemy of Us is a huge gift for both young, bright-eyed readers interested in science and adults who became disenchanted with the field somewhere along the way. Ramirez, who has forged her own path as a Black, woman scientist, undoes the trauma of bad educators and big, hard-to-distill concepts without ever sacrificing substance.

It is also quite a timely read for humans who are more reliant on—and perhaps exhausted by—technology than they were a little over a year ago. The book was released last year, in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. Ramirez recalled feeling “absolutely heartbroken” as she watched dates for a 21-city book tour disappear one by one. Many have since moved online, including a presentation at England’s Hay Festival that drew 3,000 viewers.

"I feel like a lot of people, they just got a bad shot at science," she said. "As an African-American woman, I’ve always felt like an outsider. One of the reasons that has drawn me to explaining science in the way that I do is my grandmother, who was really important to me, and I want her to feel included. I want it to be respectful. I want to meet people where they are, and I want them to feel included."

It is also, in many ways, a New Haven story. When Ramirez initially moved to New Haven in the early 2000s, it was to work as an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Yale University. She was the only Black faculty member in the department. For 10 years, she pushed for more accessible, community-focused programming in the sciences, hoping to give kids the same exposure to the field that had made her fall in love with it many years ago.

She faced a constant uphill battle, she said. During those years, Ramirez helped spearhead Yale’s “Science Saturdays,” a free, community-wide program that she described as a “nerd fest” designed for young and multigenerational audiences. She loved the sessions, adding that “I did it because it was the right thing to do.” She loved looking at attendees and spotting multiple generations of New Haveners, all enthralled with science.

What she didn’t love was the pushback she got from her supervisors for creating community programming. She left Yale in 2012, and looked for a new project. She went to high schools and colleges to talk about science. She thought about the book, which ultimately became “my best friend for four and a half years.” She read over 400 books and 200 articles before writing, then spent hours in libraries and archives working on the manuscript. Among her favorite haunts were Mitchell Library, and the libraries at Southern Connecticut State University and the New Haven Museum. In the book, New Haven makes multiple cameos, reminding readers that it too was part of the story of scientific connection.

During that time, she was also growing her New Haven circle (“I’ve only learned to be a citizen of New Haven after I left Yale,” she said). Through Sharon Lovett-Graff, then the head of Mitchell Library and now Public Services Administrator at the New Haven Free Public Library, she met designer George Corsillo during his solo show at Kehler Liddell Gallery. She asked him to design her book cover, which now features a large A and U—the letters that represent the element gold—around the rest of the title.

The inspiration comes from her digital filing system—“everything in my computer was AofU”—and a quick mock up that she drew for Corsillo. She said that when she showed him the idea for the design, he churned out a cover that she fell in love with. It fit, she said, particularly because “alchemy is all about the pursuit for gold.”

Since releasing the book, Ramirez said she's been most touched by the messages in which readers tell her "I feel like I got a second shot at science," she said. She is now working on a series of STEM-based children’s books, the details of which are still top secret.

The Alchemy of Us is available here.