Culture & Community | Education & Youth | History | Arts & Anti-racism | New Haven Academy

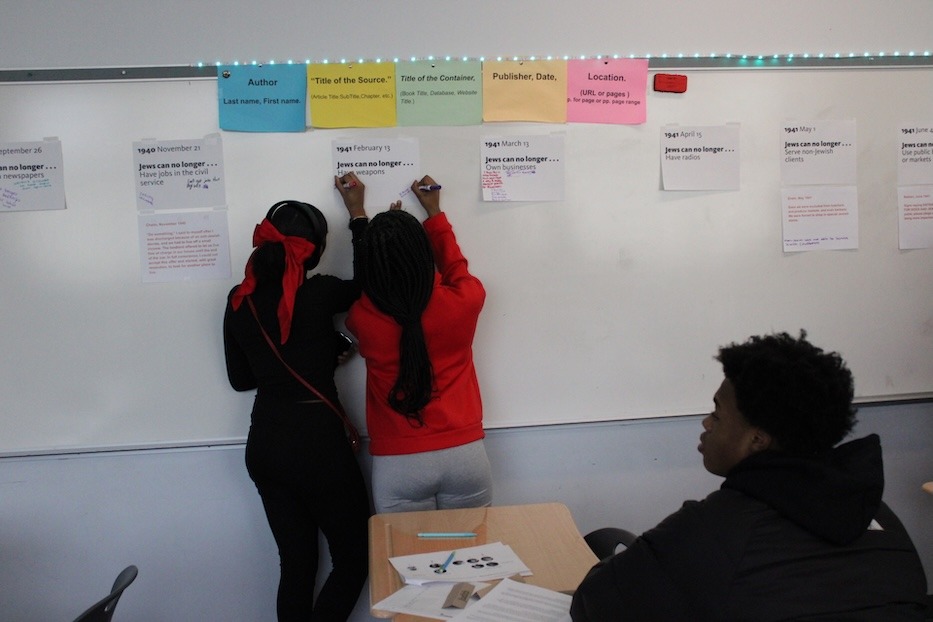

Top: Students study a timeline of events from 1940s Netherlands, as human rights disappeared under Nazi occupation. Bottom: Daphne Geismar teaches. Grayce Howe Photos.

In September 1940, a branch of the Schutzstaffel—the paramilitary arm of the Nazi Party—halted and closed the publication of Jewish newspapers across the Netherlands. By then, the Nazis had occupied the country for four months; that presence would ultimately last for five years.

In the weeks that followed, Jewish employees would be fired. Jewish students were expelled from universities and pulled from their schools. Jewish businesses landed in a directory that made persecuting their owners easier. And the most violent years of the Holocaust erupted across Europe, killing millions of Jewish people (including 1.5 million children), Roma, LGBTQ+ and disabled people, Black people, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and prisoners of war.

“Why do you think it’s important to learn about your family’s history?” New Haven Academy history teacher Jake Crutchfield asked his class of ninth graders. “Why is it important to learn about the experiences of those who came before you?”

Last month, New Haven Academy incorporated that discussion into the school’s Facing History & Ourselves curriculum, a part of the magnet school’s specialization program that also focuses on college and career readiness. As a part of the curriculum, New Haven Academy requires ninth grade students to take a history course entitled “Facing History,” in which students learn to apply their knowledge of the past to the contemporary world around them.

This year, the class included a five-day workshop. including a Holocaust survival story, artifacts, and interactive discussions that both taught students and connected them to aspects of the story. New Havener Daphne Geismar led the workshop in collaboration with New Haven Academy teachers Peter Kazienko and Crutchfield.

Geismar is an author, educator, and designer. She primarily focuses on the story of her own family, members of which survived the Holocaust while in hiding in the Netherlands.

“I knew that they ‘survived a war,’” Geismar said at New Haven Academy. “I knew there had been a war and they survived but others hadn’t and for most of my childhood that’s all I knew about their story.”

Geismar’s mother was one of three children who were separated from their parents when World War II broke out in Europe in the 1930s. The three children were disguised as average non-jewish children and sent to live with new families who protected them from the Nazis. Geismar’s grandparents, Chaim and Fifi de Zoete, stayed together and went into hiding in the roof of a church in the Netherlands until the end of Nazi occupation.

“They wanted to leave that part of their life behind, they were fearful of being different,” Geismar said of her parents. “They wanted to assimilate as much as possible and part of that was closing off the past and what had happened to them.”

After growing up with limited knowledge of her parents' experience, she received an invitation to attend an event at the church in Rotterdam that hid her grandparents. After visiting the church in 2006, Geismar dived into the story of her family’s history, discovering documents, artifacts and journals her family members wrote while they were in hiding.

Geismar spent about a decade researching and translating her family's writings from Dutch and German into English, and released her book Invisible Years in 2020. The book highlights eight narrators from Geismar’s immediate family and follows their perspectives during hiding.

“It had never felt a part of me until I did all this research,” Geismar said, “And then I owned it and I felt connected to where my family came from.”

Now, Geismar uses her family’s story to educate students. She has previously done workshops about her family’s story at Fairfield Ludlowe High School, which she has done annually since 2023. At New Haven Academy, Geismar worked with NHA Co-Founder and Program Director Meredith Gavrin to embody the Facing History & Ourselves curriculum. She added a focus on the importance of students learning about their family history and reflecting on what that means in the contemporary world.

The workshop allowed students at New Haven Academy to find true connection to the history they were learning about. Along with artifacts Geismar showed the class, students read excerpts from Invisible Years as different characters in the book, all members of Geismar’s family. Freshman Jaylin Brooks, for instance, read for the part of Judith de Zoete, Geismar’s aunt.

“It was really interesting when she brought out one of the Jewish stars one of her family members had to wear,” said Brooks. “It was just so cool to see an artifact that was from that time, and know that they had it and had to wear it, it was a very real feeling.”

“I think including Daphne's lesson added a personal touch to the history that was missing before,” Crutchfield said. “Having someone share their actual family history, and make a real human connection to the concepts we learn about in the course was a great addition.”

Crutchfield, who joined the History Department at New Haven Academy in 2019, has been teaching the class for five years. In addition to Crutchfield’s class of ninth graders, 13-year Teaching History & Ourselves veteran Peter Kazienko also followed the workshop with Geismar. Every year, Facing History & Ourselves studies the Holocaust and how its patterns may appear in discrimination today.

Jalyn Brooks and Jocelyn Augusto.

This year—at the beginning of a presidency built on anti-woman, anti-LGBTQ, anti-Black and anti-immigrant rhetoric, in which thousands of federal employees have been fired in under a month—the resonance felt especially strong.

“I think it’s important to know how you got to where you are today because we’re not all from here,” said Brooks.

Fellow freshman Jocelyn Augusto agreed. “For instance, I’m Puerto Rican and I can be a whole bunch of different things because of my family’s origin and it’s really cool to see all the different places you might be from,” Augusto said.

That approach was clear during the workshop’s five days. Day one included an introduction to the family tree—“Who are the Geismars/ De Zoets/ Cohens?”—along with a “gallery walk” that followed a timeline of disappearing human rights, particularly for Jewish people.

Day two included a deep look into what happened to Geismar’s family, and what they experienced during hiding. Day three students dove into how the experience affected the rest of the family’s lives, and what their life looked like directly after liberation. Geismar explained to the students that after the war it was people’s goal to assimilate, and try to leave as much of their old life behind as possible.

“They wanted to leave that part of their life behind, they were fearful of being different,” Geismar said. “They wanted to assimilate as much as possible and part of that was closing off the past and what had happened to them.”

Geismar also mentioned that it was more common for survivors to come forward as they got older, and as their life was coming to a close.

“It’s really common for Holocaust survivors to not talk about what happened,” Geismar said. “Especially if they’re going to move on and start a new life and then it’s also common for them to start talking about it later in life before they die.”

Then, on days four and five, students discussed how the history they’re studying can mirror and inform what’s taking place in the present day. Those conversations continued on day five, delving into current day patterns, connections, and how people might combat these issues of discrimination.

“I started hearing echoes in the world today in the taking away of peoples rights across cultures,” Geismar said in regard to starting to teach the workshop, “Which is why the second half of the workshop is researching contemporary events and studying the patterns that occur in oppression.”

As the workshop came to a close, students had the opportunity to write letters, addressed to one of the eight members of Geismar’s family who act as narrators in the book she published. The letters acted as diary entries, and many of the letters included students finding personal connections to the narrators, and finding ways where they may be similar.

Although the issue of Antisemitism, or anti-Jewish prejudice, was the reference point for contemporary discrimination, students were able to make connections to issues including homophobia, racism, sexism, and other false stereotypes.

It seemed to stick with them especially strongly as President Donald Trump aimed legislative attacks at trans people, immigrants, DEI efforts and science and science and medicine, all targets of the Nazis almost a century ago this year.

“I think it’s important to know how you got to where you are today because we’re not all from here,” Augusto said.

Grayce Howe was the Arts Paper's 2024 New Haven Academy spring intern and is now in her senior year. The New Haven Academy internship is a program for NHA juniors that pairs them with a professional in a field that is interesting to them. Grayce plans to continue writing for the Arts Paper throughout her senior year, so keep an eye out for her byline in these pages!