Culture & Community | ElderPlay Project | Faith & Spirituality | Klezmer | Long Wharf Theatre | Music | Arts & Culture | The Hill | Tower One/Tower East

Sylvia Rifkin and Isidor "Izzy" Juda at the Towers in 2021. Lucy Gellman Photos. The last photo in the story is from Lisa Reisman, courtesy of the New Haven Independent.

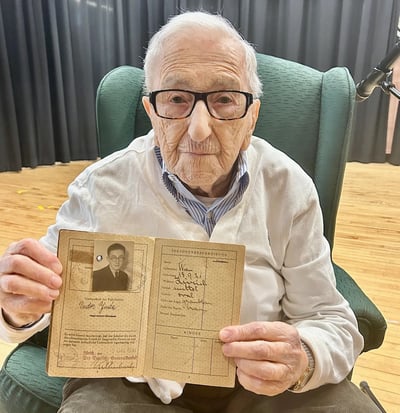

Isidor “Izzy” Juda always had a story ready, and knew exactly how to tell it. For New Haven’s youngest ears, he would start with his childhood Vienna, charting the arrival of fascism in 1938 that devastated his family, his Jewish community, and his country. For his children, he was often more interested in talking about sports and faith and music, cheering them on from the sidelines whenever he could. For his peers at the Towers, he was the mayor, always ready with a hello that would make them feel like everything was right with the world.

Juda, a radiant light, devoted father, sharp-witted friend, animated storyteller and the de facto mayor of The Towers at Tower Lane, died peacefully in his sleep at 101 years old last week. In the century that he lived, he dedicated his life to faith, family, and the liberation of those around him, from his service in the U.S. Army during World War Two to his own story of survival, which he shared with hundreds of New Haven students in the final years of his life.

He would have celebrated his 102nd birthday on September 18. In a series of interviews over the weekend and into this week, friends and family members described him as relentlessly positive, funny, opinionated, and resilient, with a capacity for love and thirst for knowledge that were deep and all-encompassing.

“It doesn’t seem real right now,” said Sylvia Rifkin, who became extremely close with him in the eight years they both lived at The Towers, and celebrated her 102nd birthday by his side in May. “Everybody knew Izzy. He said what he felt, and people listened to him.”

“He was a very positive person who always wanted to learn,” said his son, Stanley Juda, who is now a cantor in Nashua, New Hampshire and spoke to his dad several times a week. It always amazed him that the trauma that he had experienced didn’t harden him to the world, but opened him to it. “He thought that history should not be forgotten.”

Juda was born in Vienna in 1921, into an observant Jewish household that gathered faithfully around holidays until fascism upended their entire lives (in an interview in December 2021, just months after his hundredth birthday, he remembered a triumphant Hanukkah goose that his grandmother prepared every year). It was there that he developed an early love for music, from the violin that he played as a child to the opera that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Juda at the Towers in 2021.

It was 1938 when Adolf Hitler’s rise to power reached Austria, throwing Juda’s fate and his family’s—and that of hundreds of thousands of Jews living in the country—into jeopardy. As members of his family waited on visas, he made the decision to flee Vienna by himself, telling no one before he departed.

He was 16 when he left home and made it to the Swiss border, only to be spotted by Nazi soldiers and placed on a train deporting Jews to concentration camps. For the second time, he made a split-second decision, jumped from the train, and crossed by foot into Switzerland.

It would be years before he told that story to anyone, including his children and grandchildren. In 1940, Juda immigrated to the U.S, where he found and was ultimately able to reunite with his parents and younger sister. Within years of arriving, he was a member of the U.S. Army, where he fought for over two years in the Pacific Theater and was wounded in the Philippines. When he returned home, it was with a Purple Heart and trio of Bronze Stars to recognize his service.

Many of his friends remembered that detail as a remarkable part of his story—that he did not allow his own trauma to stop him from fighting for an end to a horrific war, in part because of what the war had cost him.

It was after the war that an entire chapter of Juda’s life in the United States began. In the late 1940s, Juda married his first wife, Esther, and began to build a life with her in New Jersey. Within years, the two welcomed their children, Geraldine or Geri (née Juda, now Ganezer) and Stanley.

While he spoke very little about his past with them, its imprint was everywhere. The Judas kept a traditional Jewish household, from the Yiddish that Izzy and Esther spoke to the holidays they observed and the kosher kitchen they kept. As the kids grew up, their parents instilled in them the importance of faith and learning, a commitment that has stayed with them into their 70s.

Monday, both remembered him as a deeply committed husband and dad, who was extremely present for his children. On weekends when he wasn’t at work, Juda would play catch with Stanley, a pastime that dovetailed with his fierce love of baseball, and allegiance to the Philadelphia Phillies and later the Boston Red Sox.

When Stanley began to play the sport in grade school, Juda signed up to be a driver for his team. Years later, he found a place in the bleachers as he played baseball and basketball for UConn. On Sundays when the family was still in New Jersey, he would take them out for a drive, and sometimes end up in Philadelphia or New York, taking in landmarks like the Statue of Liberty.

“There was just never a time that he didn’t have time for us,” Ganezer said.

Izzy Juda and Sylvia Rifkin performing at Long Wharf Theatre in 2019.

Both also marveled at an intellectual curiosity that was insatiable. Whether it was New Jersey or Connecticut or Florida, the Juda home was always full of music, including a piano that he could play by ear. While he never picked the violin back up again, he rarely met a genre that he didn’t like. In a performance at Long Wharf Theatre years later, he remembered seeing Glenn Miller and His Orchestra, Gene Krupa, Harry James, and Benny Goodman, all of whom fed his love of the art form.

After the family moved to Waterbury, Connecticut in 1964, Juda attended the Waterbury Symphony and operas at the Bushnell Theatre, happy to attend alone when Esther wasn’t into the repertoire. Decades later, he continued that education with visits to the New Haven Symphony Orchestra at Woolsey Hall, and classes in Jewish music history from the artist and educator David Chevan.

Chevan, a member of the Nu Haven Kapelye who also performed in an annual klezmer concert at the space, said he will miss Juda’s presence in his visits to the Towers.

“Izzy was always there,” Chevan recalled of his classes in a phone call Friday. “And he was someone who was my touchstone whenever we were at the Towers. I would be playing whatever I’d be playing, and he’d speak to me in that kind of half-English, half-Yiddish, and I would absorb everything.”

Juda’s interest in lifelong learning never left him. During Esther’s lifetime and their marriage of 53 years, the two traveled across the country, from which a heart attack at 50 and triple bypass at 60 didn’t slow him down (his children recalled that he did not stop driving until he was in his mid-90s). While he swore that he would never visit Germany, he ultimately traveled back to Vienna, and later to Argentina, where some members of his family had fled in the 1930s.

It was also during those years that he began telling the story of his past, a written account of which his children now hold fast to. In the 1980s, his grandson came to him with a school assignment on the Holocaust, according to the New Haven Independent. He started talking, ultimately crafting versions of his narrative that were appropriate for different age groups and audiences.

It was not specifically that he was more prepared to tell the story than he had been before, said Stanley—the memory of leaving Vienna remained painful until his death. It was that he realized the importance of passing the history on before it was forgotten. Juda knew acutely that he was among the last generation of Holocaust survivors. He began to speak at a time when public knowledge of the atrocities committed had begun to fade, particularly among young people.

“People can become stagnant,” Juda said during a Holocaust remembrance ceremony at the Towers in 2019. “People can forget. But I hope they don’t.”

Even into his 90s and early 100s, his age was just a number. After Esther’s passing in 2000, Juda lived in Florida for 15 years, during which he met and married his second wife, Henriette Stauber. When he returned to Connecticut after her death in 2016, he became an active member of The Towers and of Temple Beth Sholom in Hamden, where Ganezer has gone for years.

Even into his 90s and early 100s, his age was just a number. After Esther’s passing in 2000, Juda lived in Florida for 15 years, during which he met and married his second wife, Henriette Stauber. When he returned to Connecticut after her death in 2016, he became an active member of The Towers and of Temple Beth Sholom in Hamden, where Ganezer has gone for years.

He also branched into theater with the ElderPlay Project, a collaboration between the Towers and Long Wharf Theatre that existed for years in multiple forms, and has since been discontinued. Through the project in 2018 and 2019, he wrote and ultimately performed some of his reflections, which flowed from the Holocaust and World War Two to his love for his children, for his wife, and for music.

In an excerpt from the finished work, which premiered alongside young refugees and Survivors of Society Rising in June 2019, he writes about the day he was wounded in the Philippines while fighting for the U.S. Army. During an offensive on Fort Stotsenburg, he was shot in the leg, and realized he was completely alone and would have to wait until dark to receive help. “I put a tourniquet on my leg and turned it with my bayonet as tight as possible,” he remembered from Long Wharf’s Sargent Drive stage.

It was one of the ways he held stories, balancing that courage and trauma out with memories of his sister (“our family only had boys and she became the queen!”), his late wife, and the music that he always found a way to. CEIO’s Elizabeth Nearing, then the theater’s community partnership manager, remembered how much joy and ease Juda brought to the writing and rehearsal process.

“Izzy came bursting with curiosity and stories woven with music, dancing, romance, and the whole world wrapped up in short sentences,” she wrote in an email Wednesday evening. “His resilience was made of joy. I feel lucky to have known him and gotten to see him tell stories of the many lives he's lived.”

That was also true at Temple Beth Sholom and at the Towers, where he dressed the Torah in white each year before High Holidays, and recited the Mourner’s Kaddish in a remembrance ceremony every spring. Rabbi Benjamin Scolnic, who met him close to a decade ago at Beth Sholom, remembered how thoughtfully he practiced and passed down his faith.

To many, he became an embodiment of L'dor v'dor—a phrase that translates to “from generation to generation.”

“First of all, we were friends,” Scolnic said in a phone call Wednesday, praising the warmth and courage with which Juda spoke about his own survival. When Juda made it to services, he would come to the bimah to deliver an aliyah, and on Yom Kippur to chant the haftorah “When you talked to him, it was like you were the only person in the whole world. He was easy to be close to.”

Kathy Barkin, a teacher at John C. Daniels School of International Communication and a member of Beth Sholom, also remembered Juda’s capacity for kindness. When the two saw each other at services, he made a point to ask about her son, who is currently enlisted in the army. At some point, she invited him to speak to her students, which he did in 2019 and again last year.

“He will be so missed,” she said in a phone call Sunday afternoon, remembering how he picked up the phone with a cheery “Hey kid, how are ya?” during a recent call, and the two talked about how he would return in the current school year. “He is a treasure.”

At the Towers, residents and staff are still feeling his loss profoundly. As recently as this month, Juda joined the Towers’ choir, in hopes of learning and recording the Hebrew song “Bashana Haba'a” with singers in New Haven’s sister city of Afula-Gilboa, Israel. He attended a rehearsal the Thursday before he died, followed two days later by Saturday services.

“In some ways, he was kind of the voice of The Towers,” said choral director Kevin Mack, who was back Monday to rehearse with the group. “I know how much this affects the community.”

After smiling through choir rehearsal—she joined because Juda also joined—Rifkin said that it does not yet feel completely real. Seven years ago, the two met at one of the Towers’ social functions, probably a party, she said. By the end of the night, she learned that Juda had many talents, including dancing. For Rifkin, who tap danced for years and can still nail a mean tango at 102, it was a fast path to friendship.

“He could fix anything,” she said, smiling at the memory of Juda tinkering with her telephone one day, and then coming back to open a jar the next. As a friend, she adored him—and so did members of her family who visited. Her children and grandchildren loved him, and he loved them back. “Even when he wasn’t quite sure at first, he would fix it.”

When she learned about Juda’s death from Ganezer last Monday, she went to be with her in his apartment. What keeps her going, she said, is knowing that he passed “the way he wanted to,” in his sleep and without prolonged suffering.

“Without friends in a place like this, you can be very lonely,” she added. Juda was the exact opposite of that. Even when Covid-19 confined residents to their rooms and screens, he kept reaching out. It made surviving the pandemic that much more bearable.

Scolnic, who on Wednesday was in the thick of Rosh Hashanah preparations, added that Juda’s loss will be especially palpable during the forthcoming Days of Awe, as it already has been for so many in the community. In 2017, the two co-led a belated Bar and Bat Mitzvah Ceremony at the Towers, during which Juda read directly from the Torah for the first time. He was 96. For the next five years, he remained just as engaged, as curious, as excited for new opportunities to come.

During this time of year, “We think a lot about the purpose of our lives,” he said. “And Izzy can teach us about what makes life meaningful.”