Culture & Community | Immigration | Arts & Culture | Unidad Latina en Acción | Visual Arts | Arts & Anti-racism | New Haven People's Center

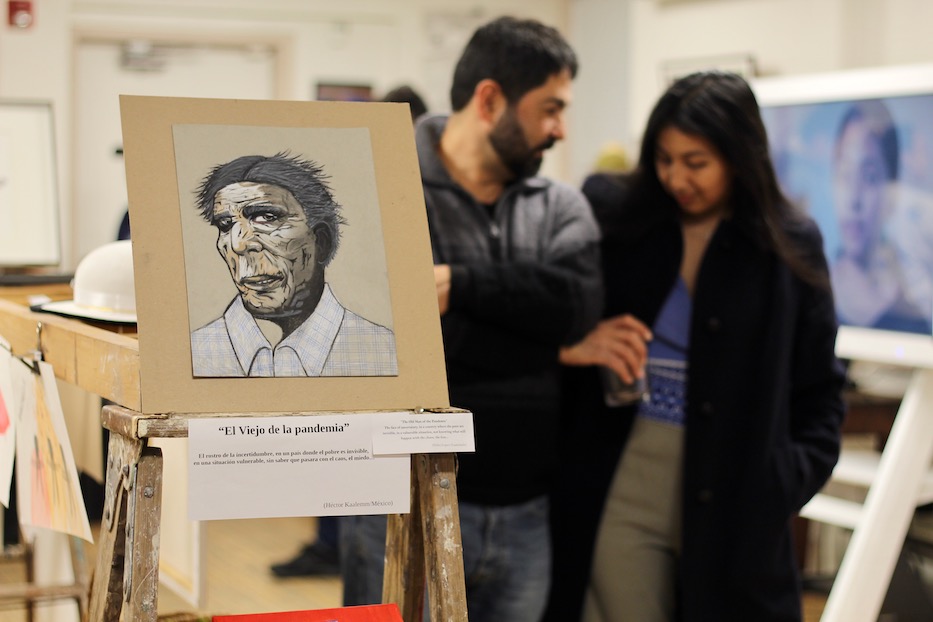

Top: Kaalemm’s “El Viejo de la Pandemia” (“The Old Man of the Pandemic”) on opening night. Bottom: Estefania Cuzco works on paper. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The three women face away from a viewer, hair streaming down their backs. In front of them, a mountain rises into the sky, handprints covering its surface. With each, fingers spread from their heart-shaped palms, reaching toward the sun. The letters MMIWG2S—Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People—scroll up the side of the paper.

A call seems to rise from the page, as if the artist has whispered: Bring them back. Across the room, a woman looks out wide-eyed from a canvas, a red handprint embroidered over her mouth.

Crisp and instantly affecting, Estefania Cuzco’s drawings on paper are part of El Arte/El sueño/La Realidad de Migrar (The Art/The Dream/The Reality of Migration), on view at the New Haven People’s Center at 37 Howe St. through January 26. Curated by Guatemalan artist Pedro López, the show brings together the work of artists Héctor Kaalemm, Silvana Deigan, Estefania Cuzco and López himself.

This year, it is part of how Unidad Latina en Acción is telling the story of immigration in the U.S.—and advocating for a better and more humane system in the process. All of the artists have a part in telling that story: Deigan is from Peru, Cuzco is Indigenous Kañari from Ecuador, Kaalemm is from Mexico.

Artist and curator Pedro López with longtime ULA member and organizer Megan Fountain. Lucy Gellman Photos.

López, whose artist-activism spans Indigenous sovereignty to environmental preservation, has brought a piece of Guatemala to New Haven for years, as he oversees decorations for ULA’s Día de los Muertos parade each year. He said that the show was months in the making.

"I had the idea of making this art to show the people the process of immigration through my work," López said at an opening last Wednesday night, as High School in the Community senior Alison Escobar translated. “I wanted to show the whole process of walking from your country to Mexico, and then Mexico to the United States. I wanted to show the horrible experience of parents having to be separated from their children or their family.”

From the exhibition’s first piece to its last, it weaves a narrative around the trauma, exhaustion, and difficulty of migration with heart-rending clarity and detail. In Kaalemm’s “El Viejo de la Pandemia” (“The Old Man of the Pandemic”), an elder looks out at the viewer, his eyes tired and skeptical all at once. Beneath a furrowed brow, he lets down his guard, features hardened by years of living in the shadows.

Kaalemm’s “El Viejo de la Pandemia” (“The Old Man of the Pandemic”). Bottom: Estefania Cuzco. Lucy Gellman 's art works to bring attention to Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women. Lucy Gellman Photos.

As he turns to his right, his skin takes on the quality of wet clay, soft and pliable with a blue-gray tint. It is cracked in every direction, skin pulling away from his cheekbones, his chin. His hair splits at the ends; his lips part to show a slice of white teeth. He is wary, and he has every right to be: this is a portrait of a man to whom time and labor have been unkind. There are centuries of history in a single gaze. The viewer, in turn, never gets his full name. He remains simply “El Viejo.”

“The face of uncertainty, in a country where the poor are invisible, in a vulnerable situation, not knowing what will happen with the chaos, the fear …” López has written in both English and Spanish on an accompanying label.

López deepens that narrative in pieces such as “La Bestia” (“The Beast”), named after the freight train onto which thousands of migrants leap and climb on their journey from Central America into Mexico and Mexico to the United States. After jumping on board at the train’s point of origin in Chiapas, Mexico, migrants travel north toward the U.S.-Mexico border, where La Bestia connects to a network of other trains. Along the route, migrants may fall from the train, risking severe injuries and death.

López' depiction of "La Bestia." Lucy Gellman Photos.

In the piece, a man stares at the cars of the train, his back to a viewer as the wheels churn slowly into action. On the ground, his left foot is firmly planted on a dry expanse of dirt; what is left of his right hangs midair, amputated just below the knee. He leans forward on two crutches, not quite slumping. On the tracks, a gap opens between cars. Its neat geometric triangle gives no indication of the danger lurking in its midst.

López said the work is based on real-life testimony that he listened to. As he described it Wednesday, he spoke with a hitch in his voice, the pain palpable.

“It explains how tough the immigration process is,” he said as Escobar translated Wednesday. “This person lost part of his leg while trying to get into the train, La Bestia, the Beast, which is one of the most dangerous trains, one of the most dangerous processes of immigration.”

Beneath it, the face of a child looks out onto the room, silently crying from behind a section of silver-gray chain link. In the painting, their arms are raised, such that it looks like their little hands are wrapped around the wire. Their eyes question everything; they seem far too exhausted for a child. As dried flowers and leaves snake through the chain link, a viewer starts to wonder where their parents are, and who will care for them in their absence.

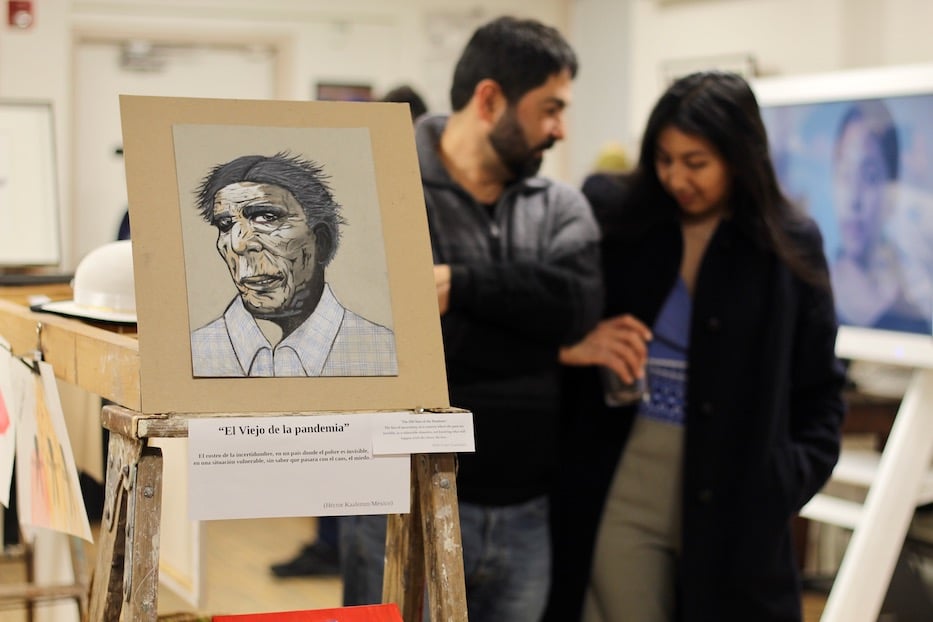

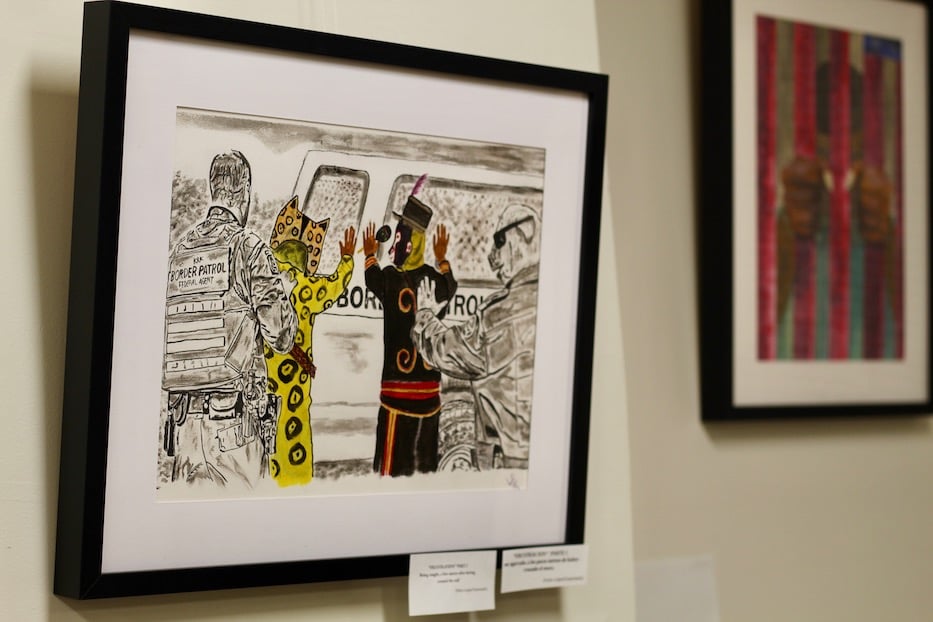

Top: López’s "Frustración, Parte I," which shows the frustration of migrants caught and harassed by border patrol just moments after crossing the border. Bottom: “The heart is how far I am from home,” Cuzco said of the drawing. “Home lives in me, but it’s also so far away from me.”

The sense that something is deeply wrong here is hard-hitting, immediate, enduring. It comes in many visual forms: López’s drawings of migrants who have just crossed, their hands flush against a cop car as they are patted down; his fields full of ghosts, thick with melancholy and tradition in “El Anhelo/El Recuerdo” (“The Memory/The Longing”); Cuzco’s tributes to the Andes of her youth; Kaalemm’s weathered immigrants, whose dreams have turned to dust.

They beg viewers not to look away, to contend with the reality that has grown under multiple U.S. presidents, to acknowledge the cost of the people and families behind each individual border crossing. In this sense, the exhibition shows not only the broken-ness of a system—children separated from their families, limbs mangled and severed in an attempt to jump aboard La Bestia, police harassing immigrants on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border—but also its sheer human toll.

That’s also very much true for Cuzco, who lives in Groton but met López last year at a vendor fair at the People’s Center. At Wednesday night’s opening, the artist walked toward the center of the room, letting the artwork tell her story one piece at a time. As she moved, a traditional Kañari beaded belt shifted on her waist, the blue beads catching in the light.

.jpeg?width=933&height=622&name=ULAExhibitionJan23%20-%201%20(1).jpeg)

Estefania Cuzco with Alison Escobar (in black sweatshirt) and Nayeli Garcia. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Born in the Andes, Cuzco said that much of her work is inspired by her grandmother Mercedes, “a healing figure for me” who still lives where she grew up. With both hands, she gently lifted a bag woven from Toquilla straw, grown and harvested in the Andes. For her, it was a craft passed down through generations, from grandmother to granddaughter. When she joined the exhibition’s planning process last year, she brought her past with her.

“I was most inspired by my heritage, and by the past,” she said. On top of a display rack, black paint sprawled across glass, transforming into the shape of an abstracted, swirling orchid. Holding the glass up, Cuzco described it as an homage to her grandmother, who called her a wild orchid “because a wild orchid will grow anywhere.” As she spoke, it became both a frame and a window, bringing viewers to another world.

Just feet from her hands, her drawing “The Temple of the Sun” looked out in bright yellows, greens and reds, the color undulating. If a viewer came close, bands of green and red seemed to move on the paper, as if it were a living heart with ventricles and chambers. Beneath the shape, the words enumerable corazón del viento scrolled out in long, delicate cursive. A paper-and-paint owl with the eyes cut out hung noiselessly beside it.

“The heart is how far I am from home,” she said of the drawing. “Home lives in me, but it’s also so far away from me.”

Cuzco has also worked diligently to bring attention to the presence of human trafficking, of which she is a survivor, and to the plight of murdered and missing Indigenous women in South and Central America. In the U.S. and abroad, she said, there is increasingly awareness around the #MMIW movement—but it often excludes whole continents in its discussion.

“We also go missing and we also are murdered,” she said.

.jpeg?width=933&height=622&name=ULAExhibitionJan23%20-%201%20(2).jpeg)

In one work, vibrant streaks of red and purple are covered with a coat of plaster, as if the pulsing, very much alive colors with which she grew up are sometimes clouded out by her memories of that time. In several drawings on the other side of the display, she has sketched her way through her love for nature, including a minimalist self-portrait with laurel branches standing in as eyes.

“The art responds to the question, ‘Why,’” she later said as ULA member Megan Fountain translated. A canvas of a woman in bright yellow, her hair worked into two long braids, looked out from the far end of the room as she spoke. A red handprint rose from her mouth. “Why did you leave? Why did you leave your land? Well, it is not safe for us.”

In her work and across the exhibition, the result is an unflinching, often personal look at an immigration system that has penalized people—Black and Brown people in particular—for crossing borders that were once as arbitrary as the concept of land ownership itself.

It also reminds viewers that it doesn’t have to be this way—and hasn’t always been. It was in 1996, when then-President Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act into law, that deportation became a much more common part of immigration reform in the United States.

Almost three decades later, the fallout from that legislation continues—including under a U.S. President who campaigned on immigration reform, but has struggled to deliver on that promise. Installed in the heart of a sanctuary city, the exhibition reminds viewers that the country’s Southern border may be as close as a neighbor, a student, a peer or colleague at the same minimum-wage job who is just trying to survive.

.jpeg?width=933&height=622&name=ULAExhibitionJan23%20-%201%20(3).jpeg)

Wednesday, López said it was also important to him to comment on the frequent exclusion of Indigenous people and Black people from the conversation. Often when people talk about immigration, he said, they are not thinking about the Indigenous people who fear and flee persecution in their own countries.

Escobar, who spent the evening both translating and taking in the artwork, noted how moving the exhibition was to her. Almost five years ago, she and her family immigrated to the U.S. from Guatemala. As a student in the city’s public schools, she often finds herself slipping between English and Spanish to accommodate other students, and to navigate her own way through New Haven.

In November of last year, she connected with ULA Co-Founder John Lugo through a fundraiser at her school. She described the work and advocacy that she now does with ULA as part of paying it forward. When she found the group, she said, “I felt like I finally have a reason to live.”

“As an immigrant, I get the opportunity to help other immigrants here,” she said. “Personally, I don’t feel like they [immigrants] get the respect, resources, and justice that they deserve. When they come here, they have the typical dream—the American dream that you hear about. Their sad reality is injustice from the government.”

Earlier in the evening, López had said the same when asked why he pulled the show together. For him, it is “the tough reality of injustice, corruption” that migrants face—and the ability people have to look away from it—that often inspires him to continue the work he does across multiple countries.

He thanked Joelle Fishman, coordinator of the People’s Center, for making the space available to members of ULA for not only the exhibition, but so much of their work in New Haven.

“This place is really important,” he said, gesturing around him. A quilt that read Labor & Community/United In Struggle hung on the wall nearby. “Knowing the history of this building, what it is for New Haven, I’m really thankful.”

“The honor is ours,” said Fishman from where she sat across the room. “We are so grateful for your work and your presence here.”

A closing reception for the show is scheduled for Jan. 25 at 5 p.m.