DACA | Arts & Culture | Theater | Yale Rep Theatre

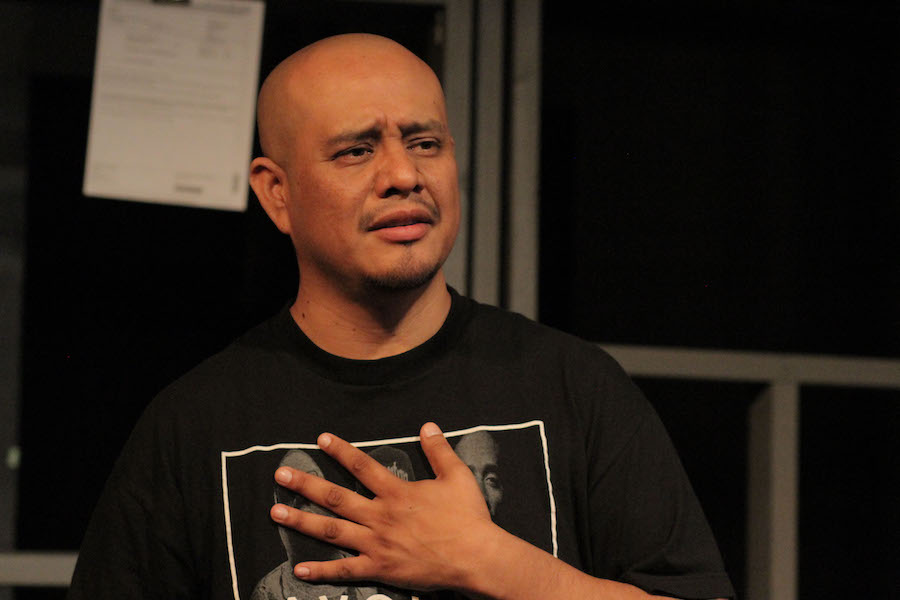

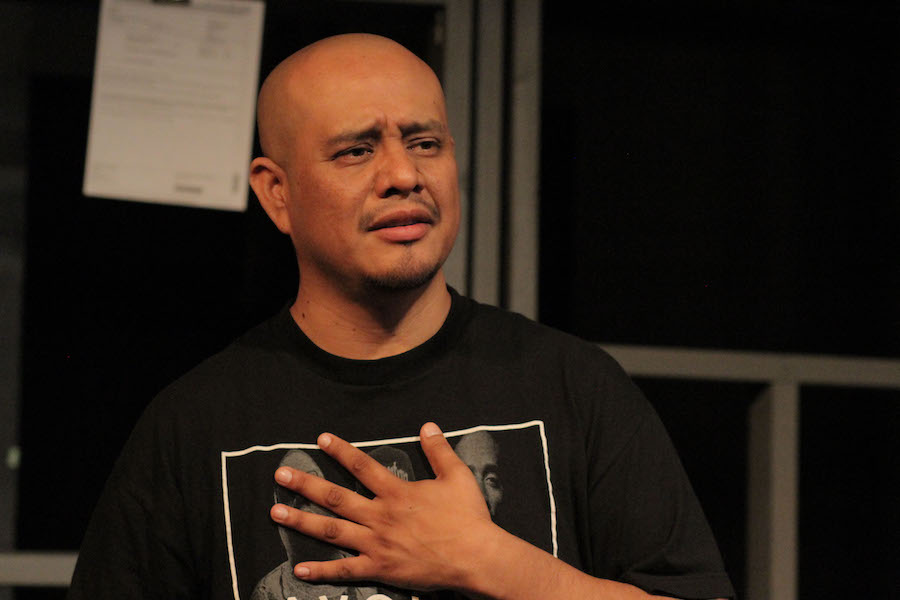

| Alex Alpharaoh performing in WET. Youthana Yuos Photo. |

Alex Alpharaoh was just two months old when he came to Los Angeles from Guatemala as Anner Alexander Alfaro Cividanis. He was several decades older, and still undocumented in the only city he had ever called home, when President Barack Obama announced a new program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, in 2012. And by the time President Donald Trump made his first moves to terminate the program in 2017, he had experienced the full spectrum of what it means to work towards American citizenship in a country that is not always welcoming as it claims to be.

Now, he has woven that history into WET: A DACAmented Journey, a vivid 90-minute portrait of his youth and life in Los Angeles, and arduous, at times punishing, journey to documentation. The play runs Dec. 13-15 at the Yale Repertory Theatre, as part of its burgeoning “No Boundaries” series. Tickets and more information are available here.

A powerful mix of poetry and unflinching narrative (the play made a stop in Hartford earlier this year), WET tells the story of Alpharaoh’s mother’s harrowing passage to the United States from Guatemala at just 15 years old, and his subsequent youth, quest for DACA status, and journey back to Guatemala on Advanced Parole, in which immigrants must establish their initial point of entry into the United States to receive documentation.

After premiering the play in Los Angeles last September, in the thick of Trump’s vows to end the program, Alpharaoh has taken the show on a national tour directed by Brisa Areli Muñoz. In advance of the New Haven leg of that journey, The Arts Paper had a chance to catch up with him about how the performance has evolved. That interview is below.

When did you decide that you wanted this story to be a living, breathing thing? Or did it seem less like a decision and more like a necessity?

Writing has always been therapeutic for me. Since I was a child, I wrote poetry as a way of processing my surroundings and my experiences. When I first came back home to Los Angeles [from Guatemala, during his Advance Parole], I was suffering from extreme PTSD and needed to unpack a very surreal experience that I had just lived through. I came back home on a Wednesday. Sunday of that week, I had a slot in my theatre company’s winter play reading series. I was slated to read a draft to a solo show I had written about being a social worker at a psychiatric nursing home.

Instead, I showed up with about eight sheets of paper that had bullet points on them, I turned on my sound recorder, and I recounted the events that I lived through. That first reading/recitation lasted about three hours. When I was done, the audience was shocked. Since then, the play has gone through several revisions, I’ve worked closely with my director and dramaturg in order to craft a really tight, concise story that I share in 80 minuted with audiences.

At one point—I think it was in an interview earlier this year—I read that you referred to presenting the story publicly as terrifying. Does it ever get not terrifying?

It’s always terrifying. It’s terrifying because there are people out there with very skewed perceptions. People that assume that POC [people of color] are somehow the enemy. The radicalization of domestic terrorists and acts of terrorism in the United States has increased incrementally over the past two years.

There is always an inherent fear that comes with being raw and vulnerable. With metaphorically stripping yourself naked on stage for the world to see and hear you. It is the most terrifying the moment before I hit the stage. It is the least terrifying the moment after I exit the stage.

What are those conversations like after your performances? Do you find that you're usually speaking to rooms of "the converted"—those who already skew progressive and believe that immigration is just and moral—or do you get people who don't see eye to eye with the narrative?

At this point in time, after performing this show in over eight states and 16 cities over the course of more than a year, the audiences have definitely been mixed. There have been instances where people have walked away from the performance with a change of mind and heart.

I wouldn’t be able to tell you if there are ever people who walk away angry or upset because I’ve never been approached as such. I think the pleasant surprise that people walk away with is that this show is not a political soapbox. The word DACA in the title may suggest that, but if people come and are willing to sit through the Journey, they’ll realize that this is a story about humanity, family, love, and home.

Certainly, the work has reverberations in New Haven—downtown's First and Summerfield Church has become a temporary home to Nelson Pinos, an immigrant who has been seeking sanctuary from ICE for over a year. Can you tell me a bit about the power of telling and hearing true and sometimes difficult Latinx stories?

We, as a whole need to hear these stories. In order for any kind of comprehensive immigration reform to pass, there needs to be human lives and stories that are shared so that others may find the courage to do the same. My journey is just one of over 14 million people that are already living in the U.S.

Of course it’s difficult to hear and see of others suffering, Latinx or other. I stand in solidarity with the African American community, I love and stand with the LGBTQA+ community, the indigenous community, the immigrant community, the Muslim community, any and all marginalized people in this country. We share similar experiences of oppression and fear.

Do you feel that the work has evolved as the current administration continues to roll back the rights of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in this country?

The epilogue changes and adjusts in order to include current events that are affecting the lives of millions. The story and the journey are set. It is at the end of the play, when there are no more lights to display, or sounds to play off of, and it’s just me and the audience. That I take a final moment to echo the atrocities that are occurring because of the policies that are being implemented or attempted to implement.