Hamden | Arts & Culture | Theater | Quinnipiac University

.jpg)

| Tamia Barnes as Shelby and Haneen Hamden as Maryam in Baltimore. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

The students stand in the common room, exasperated. Some look down at their feet, blue and purple in the light. Others sit, moving chest first toward the edge of their seats. One slouches back on the couch, as if it will absorb her full weight. Their RA is nowhere to be found, and this discussion needs to start now.

“The problem is, the problem is, all this history folds in on itself,” a voice begins in the half-dark. The line loops like poetry, and other voices join in. A metronome pulses on in the background, keeping time.

That cacophony underscores Baltimore, running this Thursday through Sunday at Quinnipiac University’s Theatre Arts Center in Hamden. Written by Kirsten Greenidge and directed by Aleta Staton, the play strikes a timely nerve, inserting itself into campus discussions around race, history, and economic privilege without ever coming across as preachy or contrived.

Tickets and more information are available here.

In Baltimore, which draws its name from Countee Cullen’s “Incident,” the audience finds itself on familiar turf almost immediately. Somewhere in the wood-paneled annals of Sudbury University—which could be a Yale or a Quinnipiac—college student and RA Shelby Wilson (Tamia Barnes) is elbow-deep in discussion with Dean Hernandez (Sociology and Journalism Professor Don Sawyer, Quinnipiac’s real-life vice president for equity and inclusion).

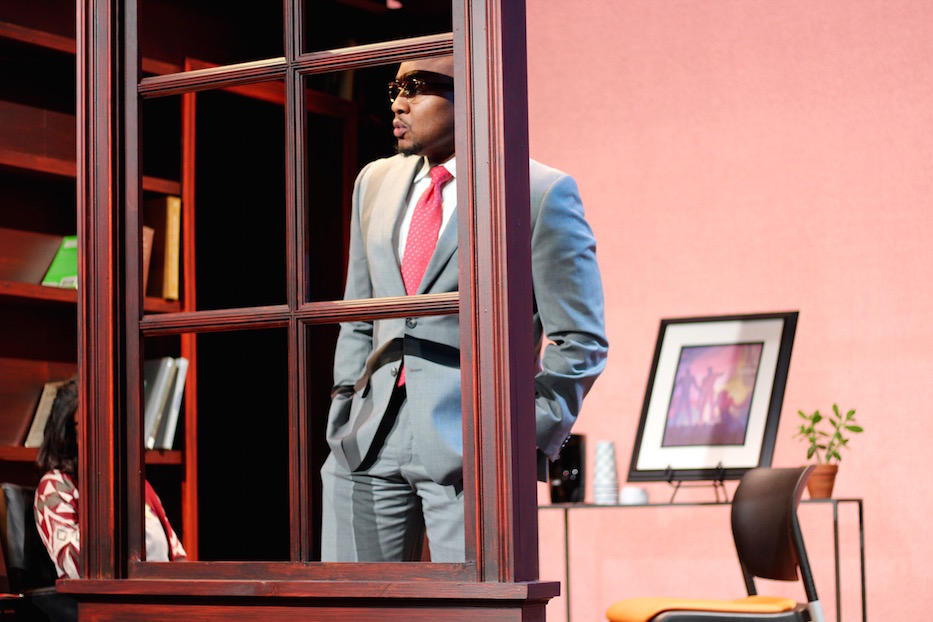

| Professor Don Sawyer III as Dean Hernandez. |

It’s not going well: Shelby doesn’t agree with much of what Hernandez has to say about the history of race, and doesn't know much of it either because she slept through his convocation address. He holds that history in his hands; she’d rather ignore the fact that it exists. He’s pensive and methodical; she just wants a new job, because the one she has is too hard.

So when her white resident Fiona (Skye McCashion) leaves a racially-charged caricature on her black floormate Alyssa’s door (Kaylin Bracey), the audience senses that Shelby might be out of her depth. Will she sink, or will she swim? Will she even jump into the choppy water?

Greenidge’s answer is more complex. With a taste for both humor and to-the-moment realism (and the blinding whiteness of private college campus), she weaves a world that feels deeply familiar, from code-switching roommates and students who self-segregate in the cafeteria to personal anecdotes about the first time students of color realized that race existed, often long before their white teachers and name-calling classmates did. While Shelby trudges through her own racial quagmire, her friend Maryam (Haneen Hamden) raises what may be the central question of the show, and of the present: what does it mean to see and be seen?

And how hard is it to do, really? A punky, pugnacious slip of a thing, Fiona hides behind her black boyfriend Bryant (Tyrell Latouche), insisting that she can’t be racist if she’s dating a person of color. Before audience members can decide to dislike her outright—which is tempting as she declares “See! I can take a joke!”—they may notice that they’ve heard her in their peers, their students, their colleagues and their family members.

| Haneen Hamden as Maryam and Nicole Mawhirter as Rachel. |

Around her, student orbit each other like nervous atoms. There is Leigh (Emiola Omotade), raised to be proud of the melanin in her skin, and equally angry and humiliated when she sees a world that is still stacked to wear her down. There’s Carson (a winning Liam Pappas), the kind-of-clueless white guy who doesn’t see why we can’t all get beyond this race thing, but reveals himself to be more complex as the play unwinds. Rachel (Nicole Mawhirter), who can school Carson on race any day, but also wants to know how her role as a Latinx woman fits into this black-and-white world, where the specter for 1619 can loom over every interaction.

In Staton’s able hands, Baltimore is raw and fresh. Tight lighting and sound design bring the set to life with a smart, interactive white board, PowerPoint-like prelude to the show, and lights that flash on and off with staticy sound beneath them. Students jump from normal interactions to propulsive, scored choreography, often driving the message home when words fail them. When the audience is left in the dark with Ysaye Maria Barnwell’s moving “No Mirrors In My Nana’s House” (sung by Sweet Honey in the Rock), it feels like it couldn’t have been any other way.

As Fiona, McCashion is a gut-churningly good case study in how quickly learned, unchecked bigotry can calcify to hatred. Around her, floormates unpack their own backgrounds in teaspoon-sized anecdotes and heady, heartrending monologues that slip right into the tenor of the play. As Alyssa, Bracey uses an economy of words to her advantage, fiery when she is speaking and also when she is not.

“I just felt exhausted,” she says at one point, and audience members hear their daughter, their friend, themselves. “Bone tired. And bare to the world.”

| Kaylin Bracey as Alyssa. |

Barnes, with palpable anxiety and drive, brings Shelby to life, teasing out a buttoned-up personality that wants to do right, but doesn’t want the mess that comes with it. Beside her, Hamdan is in many ways the soul of the show, holding it together even as her life threatens to bring her to pieces.

These struggles are relatable, with enough characters that viewers may see and hear themselves in one or many of the voices onstage. Yes, the play suggests—sometimes it’s easier not to feel the weight of history, because there’s less pain that way. But it’s a luxury that only white people get to have. Baltimore is a call to arms to get messy, and to waste no more time in doing so.

It feels right on time for the university, despite the fact that it’s been planned for over a year. Initially, Staton chose the play because “I wasn’t seeing plays that focused on diversity,” and Baltimore put it front and center in a university setting. She said she felt connected to Greenidge reading the play: both of them are graduates of Wesleyan University, where Staton experienced some of the same tensions years ago.

But it also hits a very current nerve: in August of this year, the Princeton Review ranked Quinnipiac first of 385 schools for “Little Race/Class Interaction.” The student paper picked up the story, and faculty began grappling with it in and outside of their classrooms.

“There are a lot of plays that college students can do, but this felt like it was about them,” Staton said at a preview of the show. “The experience has been transformative for us. The students and the cast are finding their voices.”

Since beginning the rehearsal process, Staton said students have come to her with personal anecdotes, stories of not fitting in on campus, and concerns about the current political atmosphere. Recently, Pappas approached her because he had seen a graffitied swastika on the way to school, and was so distraught by the image that he made a note of its location. She suggested he call the mayor of Hamden. The graffiti was down within 24 hours of the call.

That framework has translated to the show as well. After each performance, Sawyer and Sade Jean-Jacques, associate director for multicultural education, will lead a talkback with audiences, which usually comprise a mix of students and members of the public.

“We keep circling back on this history,” Staton said. “We have to start marching forward and talking to each other.”