Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School | Education & Youth | Music | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

Jayleen Mercado and Erica Washington. Both have only been playing since November 2020. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Just off Kimberly Avenue, the first bars of Bill Withers’ “Lean On Me” rippled through a music classroom, notes hanging in the air. In the center of the room, fifth graders Erica Washington and Jayleen Mercado adjusted their cellos and worked magic with their bows. On screen, Jolianys Reyes listened on mute with her camera off, her violin at the ready. At the front of the room, teacher Henry Lugo steadied his upright bass and played along.

It is one of the ways the pandemic has changed how music is taught—and learned—at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School (BRAMS) in the city’s Hill neighborhood. As some students return to school and others remain online, Lugo is one of several teachers braving the hybrid pivot. BRAMS music instructors also include band teacher Matt Fried and chorus teacher Meaghan Sheehan.

Of 404 students currently enrolled, only a percentage have returned to school for the remainder of the year. Of 71 fifth graders, for instance, approximately 40 have returned to in-person and hybrid classes. Thirty-one have remained remote. BRAMS Arts Coordinator Sylvia Petriccione said that number is always slightly in flux.

“They’re doing so great,” Lugo said on a recent Friday, prepping for his fifth grade students. “We’re all working extra hard right now, the kids first and foremost.”

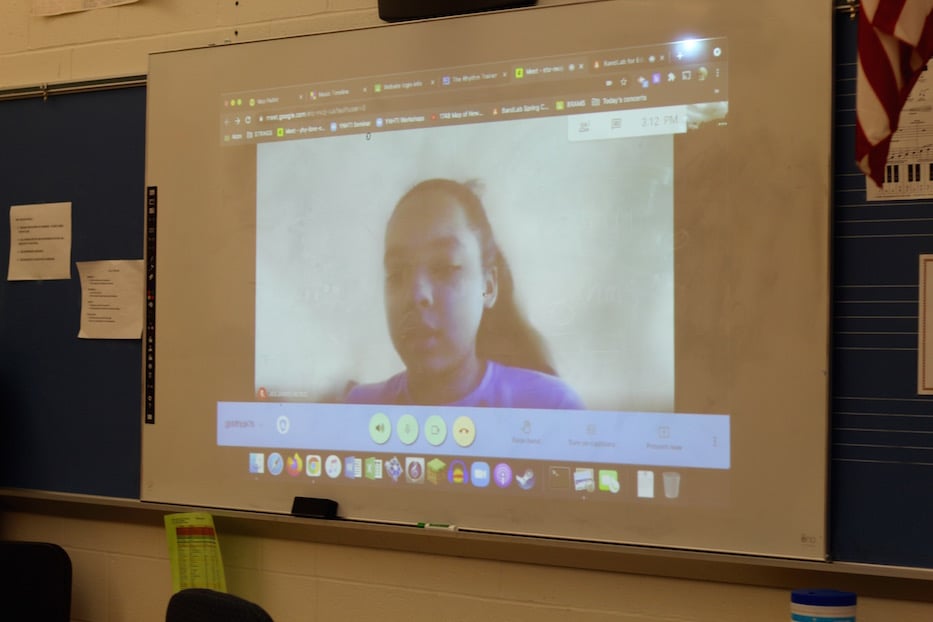

No sooner had he spoken than Washington and Mercado walked into the classroom quietly, slipping into two seats that stood six feet apart. Two cellos waited for them, laid on their sides on the floor. On a screen pulled over the board, Reyes logged in via Google Classroom. Of five students in fifth grade orchestra, one has been chronically absent all year. Lugo has 22 string students in all, two of whom he hasn’t seen since the year started.

Henry Lugo, who has been teaching at BRAMS since 2018.

Around them, signs of pandemic-era school were everywhere. Both Washington and Mercado entered the room with their masks snugly fitted around their faces, a starburst of tie-dye over Mercado’s mouth and nose. A laptop sat in the corner of the classroom, propped open and projected onto a large screen through a nest of wires. A standing microphone was attached to his computer, so Reyes could hear him.

“I like this class because it’s new,” Washington said before class started. “I just thought I wanted to do it. It’s fun so far.”

“It’s really fun,” chimed in Mercado.

Lugo navigated a series of tabs to get to the class’s Padlet, nearly bouncing with excitement. In an effort to provide culturally responsive teaching, he has dedicated the Padlet to Black and Latinx composers who reflect New Haven, including Florence Price, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, George Walker, Julio Racine, Jessie Montgomery and several others. As the timeline nears the present, it grows increasingly less white and less male.

He pulled up Bach—“so who is this party animal!?” he asked—and Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson. Before his death in 2004, Perkinson was a twentieth century Black American composer whose love for Bach was matched only by a deep love for jazz, and an ability to shape shift between the two genres while infusing one with the other. He left a historical imprint that rivaled that of his namesake, the Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

“That’s how diverse this dude was,” Lugo said, pulling up a video of cellist Tahirah Whittington playing Perkinson’s Lamentations: Suite for solo cello. While describing Perkinson’s love for Bach, he returned to his bass for just a moment, and played the first few lines of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G. He leaned into the microphone: “Jolianys, you can see this?”

“Yes!” she said back. Lugo put her back on mute to prevent an echo. The first strains of Lamentations filled the classroom.

“Much more modern than the Bach, right?” he said as Whittington played on screen. “Angular.”

Whole sections of the class are structured similarly, with one or two students listening on screen and another few in the classroom. To sustain hybrid teaching, Lugo has moved all of the material online, from sheet music to listening exercises. Friday, he pulled up ear training from the educational platform ToneSavvy, and was about to start a quiz when Mercado cut in.

“You’re not presenting!” she said. She pointed to where the screen wasn’t shared with Reyes, meaning that she couldn’t see or hear what was going on. Lugo went back to the computer, and suddenly Reyes could see the music.

There are lots of little moments like that that amount to more work, Lugo said. For instance, he can’t annotate or draw on the board—or on a physical piece of music—as he used to, because students who are online can’t see it. When he puts together ensemble pieces through BandLab—the most recent was a recording of “People Get Ready” for the school’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebrations—it takes hours of work outside of the classroom.

Washington, who said that she was excited to be picking up the cello.

What hasn’t changed, however, is the focus on music that happens during class time, whether students are physically in front of him or online. Friday, fifth graders warmed up with “Lean On Me,” playing out the first few bars with their fingers on the strings before they picked up their bows. They transitioned to “I Saw A Fox,” the newest piece in their repertoire. Reyes played along online, muted because of a delay.

Lugo tries to keep the class fun, he said. Friday, he was continually in motion, buzzing between a large computer screen, a microphone for Reyes, and his double bass at the front of the classroom. When they practice, Washington and Mercado often clap for each other between songs and offer positive feedback. They delight in surprises, including the introduction of Reyes’ huge, scaly pet lizard at the end of a recent class.

“I can’t say enough about how much they’ve picked up since November,” he said. “We try to do a little bit of everything, so that when they leave here, they will have attained enough skill to learn how to grow, and keep growing. If they can do that, then they can continue to learn whatever they decide to do.”

It has been a year in transition, he said. Lugo came to BRAMS in 2018, after years of playing jazz professionally. Last year, Covid-19 pushed all of BRAMS’ teaching online in a matter of days, as school buildings closed across the district. On March 12, 2020, teachers learned that they had the weekend to prepare for virtual classes. That Monday—as businesses shut down across the state—Lugo was meeting with students on Zoom. He used it for three weeks before the school told him to move everything to Google Classroom.

For the rest of the school year, he and students tried to navigate a platform that was never designed with instrumental music in mind. On Mondays, he checked in with all of his classes. On Tuesdays, they did lessons, trying to bridge the distance with a combination of muted microphones and sound that sometimes lagged or glitched because of an internet connection. Thursdays were for music theory and so on.

At home, students kept practicing and turning in their work. Lugo tried to figure out the next hurdle: ensemble performance without an in-person ensemble. He now knits together recordings on the online recording platform BandLab, which is easy for students to use and for him to edit. While it’s time intensive on his end, he said that the final product—students rehearsing apart, to ultimately sound like they’re playing together—has been worth it.

“There was so much confusion in the beginning,” he said. “The teachers kind of had to build the plane as we were flying it. I thought: ‘We’ll start with the stuff that they kind of know, and then figure it out.’ The mountain to climb was the technology.”

Jolianys Reyes, who plays the violin.

He spent the summer doing research, looking into online programs that could support virtual learners. Some, like BandLab and the classroom-friendly platform Padlet, were free. For those that weren’t, he asked distributors for free membership because he knew the district wouldn’t be able to afford them. Ultimately, he was able to secure a free year of materials from Hal Leonard Publishing and the website Tonesavvy, which teaches ear training and music theory.

When middle schools reopened for hybrid learning this spring, he set up multiple screens and connected a microphone to his computer, to better communicate with students who are still at home some or all of the time.

In addition to in-classroom teaching and sound mixing, he spends his weekends doing socially distanced instrument repairs and rosin drop offs for students who have instruments at home. His longest drive is out to a student who lives in Shelton. He said that it's worth the trip: students are more likely to practice if their instruments aren’t broken.

“It’s lots of extra hours, but if I don’t do the extra time, they don’t progress,” he said. “You set it [instruments, BandLab, Google Classroom] up for them, then they’re motivated.”