Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Yale University Art Gallery | COVID-19

Google Meet Screenshots.

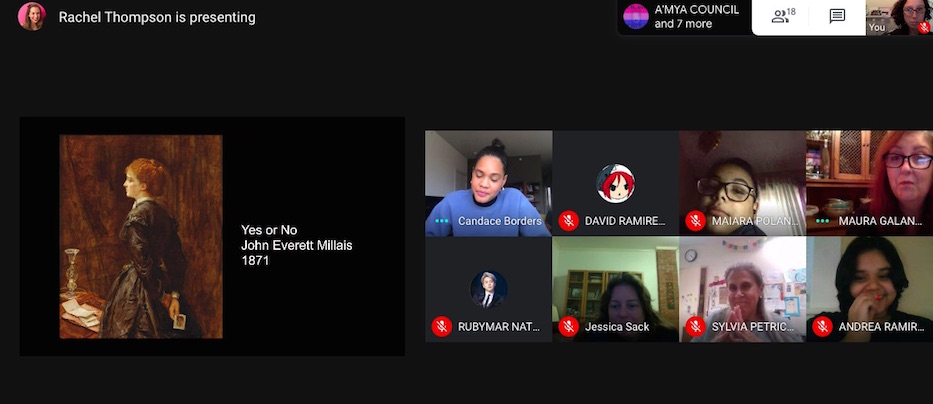

Nine middle school students started into their screens, trying to guess the title of a painting. At the center, a woman in a black dress held her arms behind her back, her left hand cupping her right wrist. In her hand, she fingered a cameo portrait that hung upside down. A letter sat, opened but unanswered, on her table.

“She looks scared,” said sixth grader Milanie Stokes. In another small box, her classmate A’mya Council started typing into her chat. Her fingers worked in silence behind a muted mic.

“Maybe she was writing something,”A’mya suggested.

Milanie and A’Mya are members of a now-virtual museum club at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School (BRAMS), a collaboration between the Yale University Art Gallery and BRAMS art instructor Maura Galante that is now in its 13th year. Once a month, students gather over Google Meet for artmaking and visual analysis with educators, gallery teachers, and art instructors who can’t be in their physical spaces due to COVID-19.

In a normal year, “the museum club members gain a sense of ownership of the gallery—a familiarity that transcends to an understanding that art museums are fun, interesting places,” said BRAMS Arts Coordinator Sylvia Petriccione. “The community connection has been invaluable for our students. They now seek out other New Haven arts resources that are open to the public free of charge.”

But the pandemic turned that format on its head. This year, both the school and the gallery glimpsed in-person reopening in the fall, but rolled back their respective plans due to a spike in COVID-19 cases. Students who had brought their friends and families to in-person museum club meetings were now in their homes all day. Petriccione wasn’t sure that students would want to meet online after a full school day in front of their computers.

Then Andrea Ramirez, a sixth grader whose older sister had been part of the club, asked if the school could bring it back. She explained that she had looked forward to the club before even attending the school. Petriccione got back in touch with the gallery.

“I always loved art because of my sister and I wanted to follow her footsteps,” she said over Google Meet. “Being here and to be able to talk about art really makes me happy.”

On a recent Thursday, students logged in just after 4 p.m., their faces filling the screen in one-inch boxes. Several greeted each other with tired smiles. One student joined from a pandemic-era shopping excursion, her face obscured by a neon pink mask. The bright lights of a high ceiling bounced behind her as she walked and talked.

“How has everyone’s week been?,” asked Jessica Sack, the Jan and Frederick Mayer Senior Associate Curator of Public Education. She held her hand in a thumbs-up motion, and then tried a thumbs down. Students hesitated before they responded with thumbs mostly raised. “Shall we start with what we’re going to do today?”

Gallery teacher Candace Borders pulled up an image of John Everett Millais’ Yes or No?, painted in 1871. The work depicts a woman standing alone beside her writing desk, deciding whether she will accept a marriage proposal. A letter sits, partly folded but still visible, on the desk. Her face is exhausted but expressionless; her lips are bloodless and drawn. Her hair sits in a messy bun on top of her head.

Instead of starting with that information, Borders asked students to guess what was going on. She noted that the painting is one of her favorites in the gallery: she was taken by its mystery the first time she saw it. Now, even with the space closed to the public and the painting accessible only from a screen, it continues to pull her in. She scanned the screen as students remained silent.

“This is super casual,” she said. “If you wanted to come off mute, please share your thoughts and let me know what you’re thinking. When we do actually open up for in-person, I can’t wait to see you all there.”

Students paused. A few squinted visibly into their cameras, studying every inch of the painting. The longer they looked, the more details appeared: the thick red-brown paint of the wall behind her. The curls barely visible in her hair as it gathered on the top of her head. After a moment, answers started filling the chat function.

“Not going lie, it’s a high quality painting masterpiece,” wrote David Ramirez Guzman, a sixth grader at the school. “And she is hiding something. Like a card.”

“She looks upset,” said Andrea Ramirez.

“Maybe she was doing something she wasn’t supposed to,” ventured Milanie Stokes. “Maybe her parents aren't nice to her and she’s scared.”

The chat was silent for just a beat. Then other students jumped back in. What if she was less scared and more restrained, suggested seventh grader Cindy Bone. David pushed back: she definitely seemed scared. Maybe she had seen family members die under the Nazis, he said.

Borders praised his guess—students hadn’t yet learned that the painting came almost seven decades before the second World War—but steered the conversation back to the woman’s face.

“You all are picking up on something,” she said. “One thing I’m super interested in is that you said that she looks upset. What is it about her face that tells us she’s upset?”

Seventh grader Jayonna Welch fixated on the subject’s somber black dress, crinkled and voluminous as it caught in the light. She saw how pale the woman’s face was, with a hint of pink color in the cheeks. She was onto something: the austerity of the painting is a far cry from the glittering golds and sumptuous, velvety blues of Millais’ work from 20 years earlier in his career, when he was a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

“It looks like she came from a funeral maybe,” she wrote in the chat.

A’mya pushed the narrative further, writing in the chat instead of speaking. Maybe she was living a double life and didn’t want to be found out, she said. By this point, two-thirds of the club had joined the chat, trading thoughts in quick succession. Borders read them off one by one.

“She was caught doing something or to tell someone that she likes them,” wrote Milanie.

“Facts,” David wrote back two minutes later. “She really read my mind.”

Borders shouted students out as “all geniuses,” revealing the title of the work to the group. She noted that in the years following the first painting, Millais’ viewers were so intrigued by the piece that he ultimately painted both possible outcomes. With both on screen, she asked students to decide which was which.

“It depends on what type of guy this guy is, but she looks like she’s about to do something off the hook.” said sixth grader Maiara Plonaco, unmuting her mic. Her voice sailed over the session, one of the first of the day.

“Maybe she feels obligated to say yes,” said eighth grader Rubymar Nater. “Her family might be poor and need the money.”

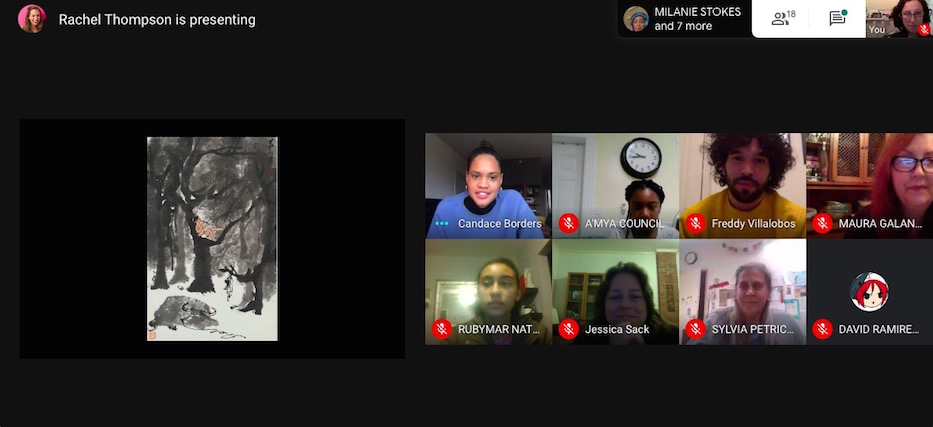

Borders said that she is moved by how artists like Millais use visual art as a storytelling device. The slide changed to Li Keran’s A Herdboy At Rest, a Chinese ink drawing from the twentieth century. She asked students to guess what was happening in the piece—and to continue the story.

In the piece, a boy sits in a tree, playing a flute from his perch. He has shed several layers: his coat and hat hang on a spindly branch beneath him, as a water buffalo sleeps beneath the tree. The scene is serene; a viewer can almost hear music floating from the piece.

“Some person looking like Tarzan is like vibing with animals,” David wrote. He recalled how during his childhood, quiet music would lull him to sleep. “I think the animal is hanging.”

Other students focused on the animal, their rapid-fire conversation filling the chat. Jayonna guessed that it might be a wolf, waiting for its prey to come down. Rubymar noticed how different the style was from Millais’ dark room and its glum inhabitant. A’mya wondered what was hanging from the tree. Maiara worried that it was a body, dangling by the neck.

“I want you all to think about what happens next,” Borders said. “I want you all to feel free to draw or to write. I want you all to just feel open to whatever calls to you.”

Students held their drawings up to the camera, some of them narrating for the first time that afternoon. Sixth grader Kani Luna read through a short story and sketch, in which the flute player is a hunter who has lulled the animals to sleep, and they snooze on peacefully. Rubymar wrote a short story in which the herd boy comes down from the tree, and takes the bull to a nearby market. In Maiara’s universe, the boy fell asleep and the water buffalo snuck up on him.

Freddy Villalobos, a gallery teacher and graduate student at the Yale School of Art, held up a drawing in which the animals lost their temper at the music. A monkey had entered the frame and snatched away the flute. Students smiled on screen as he spoke.

“I think it's great that were able to talk about art and view art and have a new experience together virtually,” wrote Rubymar in the chat.

Before she signed off, Borders encouraged students to keep drawing through their isolation, as school remains remote and the gallery’s doors stay closed to the public. She noted that she looked forward to hearing more from students at their December meeting, the curriculum for which was still up in the air.

“I want to hear what happens next,” she said. “Like, what the next chapters are.”