Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Yale

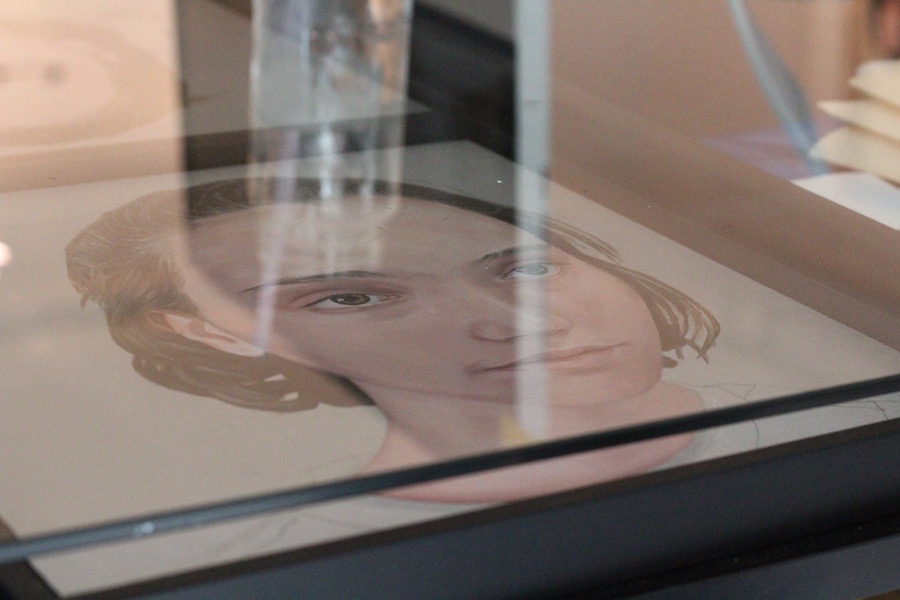

| The portrait installed in Yale's Sterling Memorial Library. Ian Christmann Photo. |

Perhaps it’s the woman in high-waisted pants, hands at her hips and eyes still shifting under a messy bun, who yanks you into the portrait. Or the one in red in the lower left corner, who just looks so very ready to be done with the task at hand. Or the woman in a tight, long brown tweedy dress that holds a beaker of deep purple liquid and examines it head on.

In another world, they might be best friends. But they’re so immersed in their work that they hardly notice each other.

It’s a portrait of the first seven women Ph.D. students at Yale, installed two years ago at Sterling Memorial Library, and now accompanied by a historical kind of pendant in Davenport College. But for the artist Brenda Zlamany, it’s also one of two paintings that marks a recent, and ongoing, homecoming to New Haven after years away.

| Zlamany in her studio in 2018. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Zlamany lives in New York City, in an airy apartment overlooking the Brooklyn Brewery on one side. Art winks out from the walls—bright oil portraits of friends and fellow artists who have posed for her for close to three decades living there, and portraits of her teenage daughter Oona that she's painted each year since she was born. She moves around the space as a detachable part of it, as if she sprouted from the ground in Bushwick one day with a paintbrush. But her roots stretch back to New Haven, still embedded deeply in the city’s fabric.

Zlamany was born in New York City in 1959, moving from Manhattan to Queens with her family as a young kid. School wasn’t easy for her: instructors at her Catholic school made her sit on her left hand, convinced that it was a sign that she was sinister. She struggled with dyslexia, made worse by the fact that she couldn’t use her dominant hand.

So at six, she decided that she wanted to be an artist. At the time, she recalled, “all I could do well was decorate the church for Easter and Christmas.” She had floated other ideas by the mother superior at school: a nun, which the school nixed because she was left handed. An astronaut, which the school informed her girls didn’t do. So she suggested: what about a painter? That was fine, the mother superior said.

“That became my career choice very early on, which is not bad,” she joked in a recent interview. “Most people are lucky if they get their third choice career.”

| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

For elementary and middle school, that dream anchored Zlamany. Midway through elementary school, a teacher urged her parents to let her transfer into a school that would let her use her left hand, which landed her at a second Catholic school in Queens. By middle school, she assumed she would attend the High School of Art and Design in the city.

But just as she was going into ninth grade, her family moved to Huntington, Conn. where she attended Shelton High School. Her dad’s company had an office there, and the offer of the suburbs seemed to pique his interest. But for Zlamany, it marked a radical change.

“There was something very snooty about the area,” she said. “There was a zoning law, and all the houses had an acre of land. My parents did not mow the lawn. They were letting the thistles that looked really pretty [grow]. And a couple of men came that first summer and said, ‘If you do not mow the lawn, we will mow it for you.’ Like, we did not fit in.”

Zlamany struggled to adjust. Her high school was so big that the student body had to attend in split sections, meaning that she went to school from 7 a.m. until 1 in the afternoon. Because her mom couldn’t drive and was tending another baby at home, the young Zlamany would hitchhike until dinnertime. Once she had started, she developed a kind of routine, interviewing the people who gave her rides until it was time to come home.

| Oona. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

One day into her freshman year, she got picked up by Nancy Shestack, a graduate of Yale Law School who was teaching at the then-nascent High School in the Community (HSC). Shestack was married to Alan Shestack, then the director of the Yale University Art Gallery Director. She invited Zlamany to their house, nestled in the city's East Rock neighborhood. As soon as she entered, she was transfixed: prints from the artist Jim Dine beckoned from the walls like old friends. She started using the home as a second sort of home base, drawing there after school ("really, showing off," she joked) to pass the time until she had to get back to Huntington.

Nancy Shestack encouraged Zlamany to apply to the then-young Educational Center for the Arts (ECA) and HSC, which had been founded just years before as a “school without walls” in 1970. She got into both.

At the time, the young artist was still living in Huntington, about a 50-minute drive away from New Haven. So she’d hitchhike each day, spending more and more time in New Haven as the semester bloomed before her. Then she started just not coming home. And somehow, she recalled, “my parents did just not seem to notice.”

In New Haven, her world opened up again. At HSC and ECA, classrooms were populated with Yale alumni and Yale grad students including the artists Earl Gordon, John Ingram, and Anna Bresnick. With no home base, she moved around constantly, crashing with Yale professors who had communes, classmates at HSC who needed roommates, an apartment on Norton Street for $30 a month.

Then there was a furnished apartment she shared with someone who worked a night shift, where she would roll out of bed in the morning, and he would crawl into it. To make ends meet, Zlamany worked for the city’s CETA program, completing murals as part of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act.

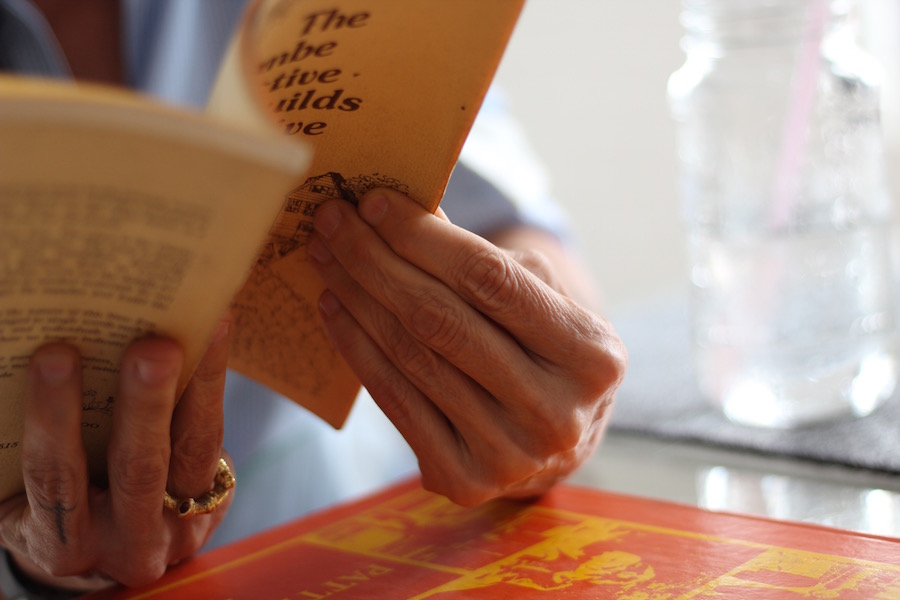

| Zlamany reads from a book she illustrated at HSC. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

“I didn’t think of myself as homeless,” she said. “I thought of myself as liberated.”

“I think New Haven was grittier then, but it was not worse,” she added. “Like, the cleaned up New Haven that you have now is not necessarily a better place. ”

At some point in high school—she can’t remember exactly when—someone recommended Yale’s now-defunct “College Before College” program, a pre-college program where 25 local students could take up to two college classes per semester. Zlamany opted for graduate classes with now-revered artists and academics: printmaking with Gabor Peterdi, painting with Lester Johnson, anthropology with George Kubler among others. As she paired her studies at Yale and a pre-college program at Albertus Magnus with coursework at ECA and HSC, a world without boundaries emerged.

"Travel has been really important to my work and understanding other cultures," she reflected. "Just early on, being at Yale, delving so deeply into other cultures ... it really made me look outside of myself. And it made me know how to enter into other cultures. I think it formed me."

Despite moving 16 times in under four years, Zlamany said New Haven never stopped feeling magical. At Yale, she watched as the globe expanded far past Connecticut and New York, doors opening on cultures she’d never heard of. She dabbled in video art and photography. Then she’d turn around and take classes at HSC that included geodesic dome building, dance, and science where students cooked mung beans and baked granola to measure the effects of good nutrition. She illustrated a children’s book where all the pronouns were gender nonspecific.

“It was just an amazing time,” she said, crediting her learning in those years for work she did much later on a Fulbright in Taiwan. “For people who go to Yale, it’s just a college. For me, it was a lifesaver.”

“If it hadn’t happened, I don’t think my life would have gone well,” she added. “Like, I don’t know what would have been available to me.”

Zlamany went from New Haven to Wesleyan, longing for a quiet, enclosed place “where I could really focus on myself and my studies.” Then after her time in college, she doubled down on figurative painting for which she is now widely known, drawing on the interdisciplinary training she’d had at ECA to enter a field she saw (and still sees) as often reserved for white men. Her career bloomed, jumping from a series on bald artists to birds, from birds to portraits of friends, family.

Her friends in the art world multiplied—the artists Chuck Close, Alex Katz, Christian Leigh, Leonardo Drew and tens of others, many of whom she painted. She traveled, drawing on her knowledge from anthropology classes she’d taken years before as she did portraits in Taiwan and Tibet. She started a long-term itinerant portrait project, rendering subjects in watercolor in real time on her travels and back in New York. And, she said, she never stopped thinking of New Haven.

| Ian Christmann Photo. |

Then in 2014, a friend who gets the Yale Alumni Magazine brought her a blurb that had caught her eye—the university's Women Faculty Forum (WFF) was holding a competition for a portrait of the first seven women to earn doctorates at Yale, inspired by a 2009 symposium on women at Yale. It was a group of women who had earned degrees in romance languages, astronomy, chemistry and literature. The project seemed like it was made for her, Zlamany recalled.

“I wanted to win very, very badly,” she said. “I just thought, ‘Oh, that’s my project.’”

In the first phases of the competition, she submitted images of her current work, portraits that looked their viewers straight in the eyes. She got to know the women: sisters Cornelia Hephzibah Bulkley Rogers and Sara Bulkley Rogers, who blazed trails in Spanish and civics at the end of the nineteenth century; astronomer Margaretta Palmer, who stayed on at Yale afterward to improve the library; literary scholar Mary Augusta Scott, who went from Yale to become a professor of English at Smith College by 1900; English scholar and suffragette Laura Johnson Wylie; poetry scholar Elizabeth Deering Hanscom; and chemist Charlotte Fitch Roberts.

When Zlamany made it to a second round, she developed a sketch, obsessively studying the women’s biographies. At the time, Yale didn’t even have portraits of all the subjects, so she dug into other university archives, tracking one down at the University of Chicago and finding that Sara Rogers had written under a male pseudonym. She became enamored of Wylie, who went on from her time at Yale to head up the Dutchess County Suffrage Organization from 1910 to 1918.

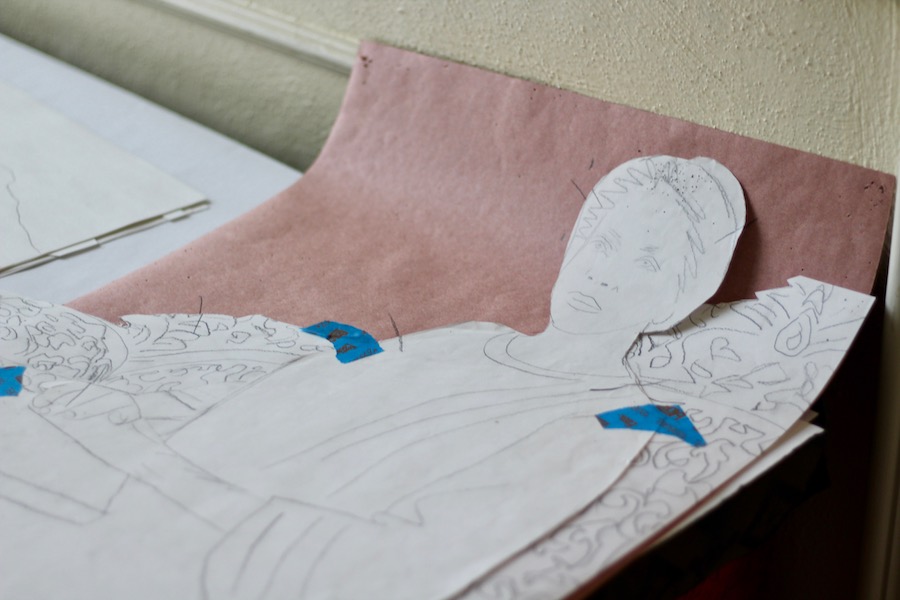

| Some of Zlamany's hundreds of cutouts, on display at the Institute Library. |

Back in New York, Zlamany threw herself almost entirely into the painting. She took a month off from other work, posing in period outfits with her daughter Oona at a nearby vintage shop that let her rent out a room for an entire day. She worked around the clock, closing big double-doors in her apartment, under which her daughter would slide plates of food. In New Haven, WFF co-chairs Laura Wexer and Paula Kavathas were taken by the submission.

“Brenda’s sketch, to me, was overwhelmingly compelling,” recalled Kavathas, a professor of Laboratory Medicine and of Immunobiology at Yale University School of Medicine who served as WFF chair until 2017. “As a scientist, it was important to me that two of the women were in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) fields. When you look at her portrait, the way she has integrated symbols and examples of their scholarship ... I thought she did a beautiful job.”

Zlamany landed the commission. After working the figures around the canvas, she started to paint. The piece was ultimately unveiled in 2016.

“It was coming full circle,” she said, adding that she made sure to work a portrait of herself into the glass of Roberts’ beaker, to make sure that “I’ll always be included” in the painting. “I’m forever in Sterling Library.”

And she is, on display for tours to see when they go by daily. Bridging time and space, she's surrounded by seven comrades who look out benevolently, severely, cautiously on a temple to knowledge that now includes their narrative. While she said she originally thought the beaker self portrait was cryptic—WFF members originally thought it might be one of Roberts’ rumored female lovers—she’s since heard tour groups mention it, a secret that’s not so secret after all.

“I think that is an important change that her work has brought to the campus,” Kavathas said. When she finds herself close to the library, she stops to duck in and look at the portrait for a while. She’s listened as tour groups pass by it, telling prospective students and eager parents about the women who earned these degrees at the turn of the twentieth century—and the woman watching from the beaker. It has changed the conversation, she said.

So has a sort of pendant ensconced in Davenport College. Last year, Yale reached out to Zlamany again, with a commission to paint a portrait of departing Davenport College Head Richard Schottenfeld. Schottenfeld wanted to be painted with eight other people, a mix of professors, students, and employees of the university with whom he’d formed friendships over decades at the school.

| A side-by-side detail of the Davenport College portraits, which are spaced across from each other on a long wall. Ian Christmann Photo. |

The gathering, which Zlamany extended over two canvases, includes three Davenport College alumni (read about those students here), historian Paul Kennedy, East Asian Languages and Literatures Professor Kang-I Chang, Davenport custodian Glaston Dubois and cafeteria worker Joanne Ursine, and the late Carolyn Haller, who worked at Davenport for eight years and the university for 16 before her death from ALS in 2016.

Zlamany said she was careful to paint Haller in her wheelchair—not just to contribute to the painting’s diversity, but to honor a woman faithfully in memory as she had been in the final stages of her life.

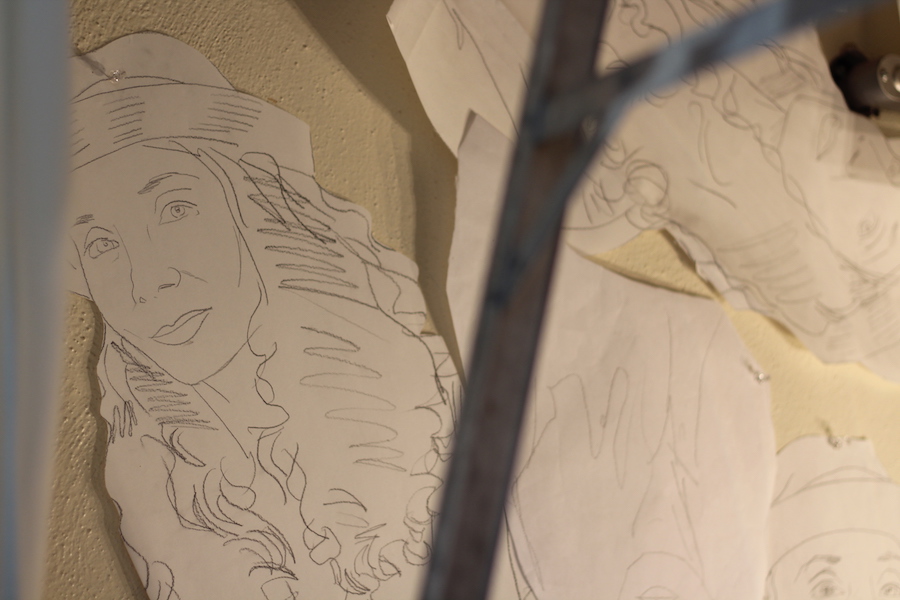

The artist estimated that she photographed each living subject 600 times, in sitting and standing positions. Then just as she had for the Sterling portrait, she made large paper cutouts of each figure (she said that she has hundreds at home, looking for a place to live), “and I moved them around like chess pieces” to figure out the relationships that each subject had to Schottenfeld, to each other, and to the portrait.

One student insisted that he needed to be talking to Haller, because she’d helped him so much with the admissions process when he was applying to Yale. Another seemed like he should be close to Schottenfeld because the two had embraced as Zlamany watched, observing their interactions for the piece.

| Preliminary sketches for the portrait that Zlamany still keeps in her studio in Brooklyn. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

“I really liked the idea of what he was trying to do,”Zlamany said. “And I think it is important for students and communities, and for people to see iconography who represents who they are … I wanted it to not be about social hierarchies, but really about the feelings that people have for each other. ”

As the piece evolved, she arranged and rearranged bodies, ultimately finding a configuration that worked across two canvases. There was one final touch: she worked a small portrait of herself into the coffee cup, a shimmering reflection in its porcelain side.

Never, she said, has she not thought of a kind of debt that she owes both Yale and New Haven. Now that she has returned to the city multiple times—she was also part of the Institute Library’s exhibition Shelf Life last fall—she said she’s hoping to come back more often.

“It was a great time,” she said of her years here. “I wouldn’t give up anything that I had. If being at home with parents and being a normal kid would mean that I wouldn’t have done … there’s not a single thing that I would give up.”