Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Hamden | Arts & Culture

| Carmen Parker: “I’m a mother who has watched Hamden public schools systematically display an ineptitude in providing a safe learning environment for our children of color." Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Carmen Parker was excited when her daughter announced she would be in a class play. She was horrified when her daughter announced that the role was for “Enslaved African 2.”

She was horrified again when she learned that the teacher was put on leave, instead of given the educational resources to learn from her mistake and return to the classroom.

Tuesday, Parker brought that story to the Hamden Board of Education’s Equity Committee, demanding a more accountable public school system in a four-hour meeting that covered minority teacher recruitment and retention, equity initiatives in the city’s public schools, allocation of more city and state dollars for teacher development, and better integration of the Hamden public school district.

Hamden Schools Superintendent Jody Goeler suggested that the play was not reflective of the district. He added that the district has embarked on the “very difficult work” of making a more equitable public school system, and the play is an aberration. Of 5,400 students in the district, 60 percent are students of color. Ninety percent of teachers are white.

Throughout the night, Parker’s comments became part of a larger discussion of what happens when widely accepted educational material, sometimes deemed as artistic or canonical, becomes a destructive force in the classroom. And what happens, in turn, when teachers do not have the district-wide support, insight, and lived experience they need to undo racism in their teaching.

“My Daughter Was Sent Home A Slave”

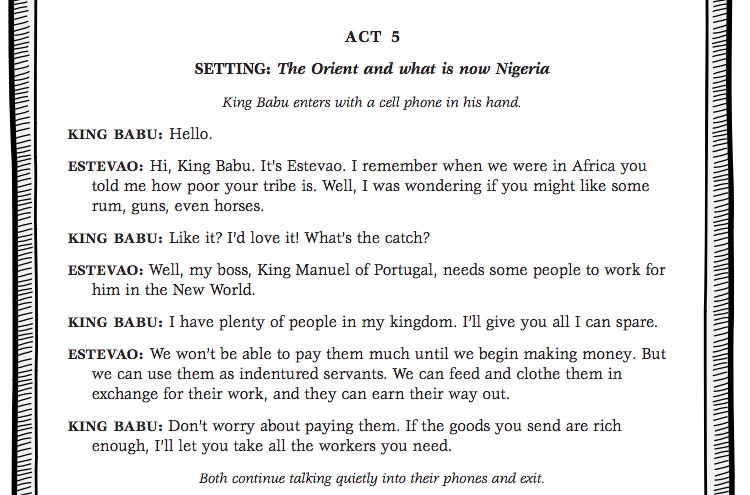

| An excerpt from the play. |

The committee meeting came on the heels of Parker’s news, first reported Tuesday afternoon in the New Haven Independent, that her daughter was learning about the transatlantic slave trade through a play titled “A Triangle Of Trade,” in which she was playing the role of “Enslaved African 2.” The 10-year-old is a fifth grader at West Woods Elementary School, where she started last year after the family moved from Georgia.

“I only learned about the play because she was talking about it at home,” Parker said before the meeting, noting that the response from the town’s board of education has been to penalize the teacher, rather than the system in which she is working.

Her daughter was originally excited to perform, Parker recalled. At 10, she is a spelling bee champion, science fair winner, and math whiz. She can play the cello, viola, and violin. She spent part of last summer at a theater camp. She loves school, including a teacher who has since been placed on administrative leave.

But when Parker asked about the daughter’s role, she was floored by the answer. She learned that the play was taken from a collection on colonial America released by Scholastic almost two decades ago. Amidst read-aloud scripts on the Jamestown settlement (Scholastic has removed the parts about prison labor, early capitalism, and genocide), the Salem Witch Trials, and first Thanksgiving “feast,” one play titled “A Triangle of Trade” chronicles the fifteenth-century expansion of the transatlantic slave trade.

The work (read more about it here and here) uses levity to describe the evolution of the slave trade between Portugal, Spain, and West Africa. In one scene, Christopher Columbus has a spirited back and forth with Queen Isabella of Spain, who is so excited about the discovery of gold that she encourages him to keep "discovering." In another, a Portuguese trader rings up an character named "King Babu" in West Africa, who readily offers his people as human chattel in exchange for wealth.

In another, Parker’s daughter was to lie down, as if inside a slave ship, and speak about how much pain she was in. Those were her only speaking parts in the play.

| City Council Member Justin Farmer: “We can’t have this conversation amongst ourselves as adults and allow the children to process this themselves." |

Parker was floored. A transplant from Georgia, she is a third generation doctorate holder, with medical training from the Medical College of Georgia and the University of Pennsylvania. Her work as an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine is dedicated to undoing racism and unconscious bias in medical practice. She and her husband Josh didn’t expect to find it in their daughter’s school assignments.

"I’m a mother who has watched Hamden public schools systematically display an ineptitude in providing a safe learning environment for our children of color,” she said Tuesday. “My name is Carmen Parker and my daughter was sent home a slave.”

When Parker pressed the issue at West Woods, she explained, the play was cancelled and her daughter’s teacher was placed on administrative leave. Tuesday, she urged Goeler to reconsider, noting that the district, and not the teacher, is to blame.

She called for the removal of West Woods Principal Dan Levy, pledging her support for her daughter’s teacher with the hope that she can learn from the experience. The experience, she explained, has been painful on multiple levels: her daughter has started asking if the teacher's removal is her fault.

Parker called for the type of incident reporting system that she sees in the medical profession. In that system, she explained, all professionals are trained in how to use the system. After incidents are reported, there is a committee that reviews each incident.

When the committee deems it appropriate, they implement a course for corrective action and remediation, so physicians can learn from their errors and return to the field as better professionals.

“Hamden’s only language on correction is to hold their front-line educators more responsible for their actions than they hold the principal,” she said. “To be more plainly spoken, I hold Principal Levy more accountable for this incident than the educator in the system that has been placed on leave.”

“Hamden has clearly demonstrated that many leaders are desensitized and habituated to extreme racial injustice and thus unfit to lead a diverse district to meaningful change,” she continued. “ … Do not make a woman a scapegoat for a system that did not support her.”

Tuesday, she also distributed an image that a school administrator gave her as “a more accurate educational resource.” It was an undated, unattributed engraving of Black Africans working on a sugarcane plantation in the West Indies. The school only relented after Parker pointed out the use of diminutive scale and physiognomy on the bent, partially-naked Black bodies in the image.

“When a teacher is identified of needing help, it is Hamden’s job to help her, not chuck her,” she said. “She is not a scapegoat here. She didn’t design this on her own.”

“I will not stop,” she continued. “These changes will be made, or I will bring everything down with every ally I have at Yale and [with] my minority leaders. You will fix this. The amount of effort it takes is up to you. I will escalate for every bit of resistance you give me.”

Not An Isolated Incident

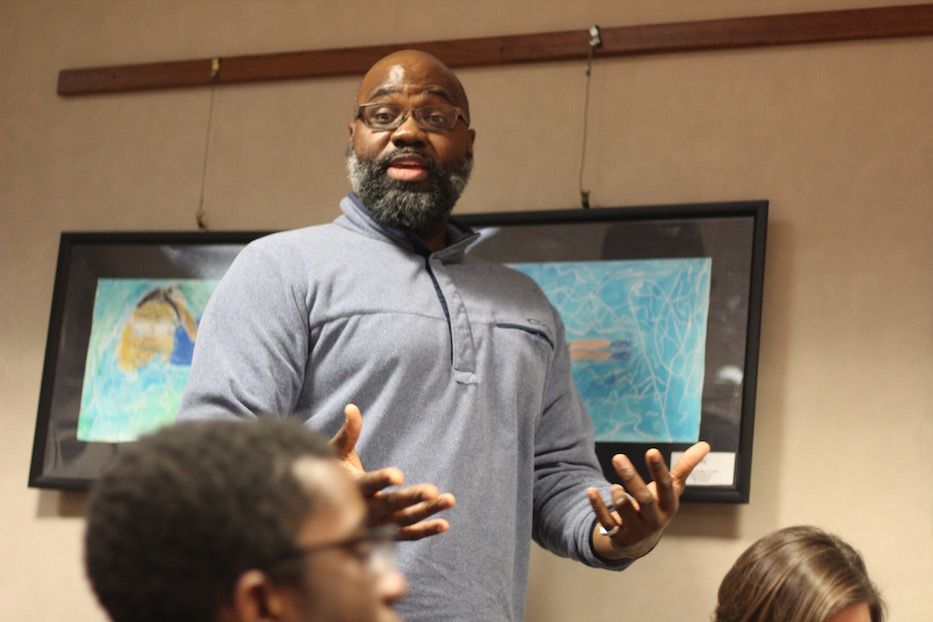

| Professor David Canton at the event. |

As she spoke Tuesday, Parker received support from other parents, educators, and town and state legislators in the room. Lauren Garrett, whose children have had the same teacher as Parker’s daughter, noted that curricular development needs input from educators of color—and more teachers of color in the classroom themselves.

David Canton, associate professor of history and director of the Africana Studies program at Connecticut College, stressed the importance of consulting with local scholars, including himself and SCSU Professor Siobhan Carter-David. Without historical context, he explained, how can teachers be expected to understand the creation and history of race, racism, and slavery in the United States?

“If you’re really serious about this, you can’t do it for free,” he said. “You need historians, scholars. That’s just the reality if we’re serious. We get trained scholars right here … local people that can do this work.”

Rashanda McCollum, who has an eighth grader in the district, recalled having a similar discussion with a teacher five years ago, when her daughter came home with a list of 35 “Connecticut notables” on whom she could write for a biography project.

Only one was a person of color. None were women of color. The year before, her daughter had received a similar assignment with no people of color at all. When McCollum submitted an expanded biography to the teacher, she was informed that it was too late to change the assignment.

“This assignment is a disservice to all students, minority or otherwise, who are no less deserving of a culturally rich and historically accurate understanding of the same pioneers who have shaped our state and country,” she wrote in an email at the time.

Justin Farmer, who sits on the town’s legislative council, added that both students and teachers need to be part of conversations around equity. He returned to the fact that Parker’s daughter selected her own role, calling it a symptom of a system mired in institutional racism.

“We can’t have this conversation amongst ourselves as adults and allow the children to process this themselves,” he said.

“This Is Very Difficult Work”

The discussion comes at a moment when Hamden’s Board of Education has identified equity as a priority, but has not defined exactly what that means. In April of last year, the board formed an equity committee, while also directing its efforts toward minority teacher recruitment and retention. Across the district, leadership is implementing implicit bias training, culturally responsive teaching, and conversations around the opportunity gap.

“I think it's important that we know that this was not a play that was part of our curriculum,” Goeler said Tuesday. “It was not something that was endorsed in instructional practice. It is not something that was part of the work of the board or the administration. The teacher made a choice to use this play— in my view it was a bad choice—and we're dealing with that.”

“As a district, we're deeply involved with work around equity, work around culturally responsive classrooms, and work around implicit bias," he added. "We're having these very courageous conversations across our district.”

But as educators spoke, it became clear that many do not have the resources that they need to implement structural changes. While some have tackled the challenge head-on—like using local food security data in a high school statistics course—others have found themselves challenged by new material.

Julia McNamee, director of K-12 language arts for the Hamden Public Schools, explained that the department “had a long way to go, but we’ve tried to do a lot.” She praised the implementation of new units on immigration, civil rights, and fantasy, noting a number of new titles by Black, Latinx, and Indigineous authors that have become part of the curriculum.

She expressed excitement over a new digital resource called Padlet, which has allowed for a greater depth of reading and multimedia material. And she mentioned that the department is working to close the opportunity gap, from using learning specialists to expanding AP course availability.

But she also said she has struggled with white teachers who don’t always feel equipped to teach authors of color, or to work with older texts with which students have voiced their discomfort. When she recalled replacing copies of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that used “the n-word” with one that used the word “slave,” committee members suggested a different alternative: drop the book entirely.

“Why are we stuck reading Huck Finn?” asked member Roxana Walker-Canton. “In other words, we can get the same type of universal themes and argument from other texts. In other words, if we’re really talking about for real kinds of changes when we talk about diversity, it can’t be just—what’s the phrase—can you put new wine in an old flask? We’re just putting a band-aid on it. And it’s all connected.”

“It can’t be an add-on,” she said. “We have to tear down the system and build it back up.”

Walker-Canton, who has served as an educator and documentary filmmaker for years, added that schools desperately need more diverse voices. Melissa Kaplan, a professor of English at Quinnipiac University and member of the equity and curriculum committees, agreed.

“My concern is that even when you use a text that substitutes that word, it’s still there,” she said. “And I think it actually, in a way, it does its own form of violence by making the violence and then trying to cover up that violence. It whitewashes that violence. ”

“You cannot erase the power dynamic of a white teacher in a position of authority teaching to a diverse group of students,” she added.

What Comes Next?

Goeler also noted that the district has just started work on Hamden’s Diversity Advisory Committee with educator and consultant Sarah Medina Camiscoli (pictured above). The advisory committee will be a group dedicated to “deep listening” with parents, students, community members, teachers, and school administrators.

Members have already been nominated from each of the town’s schools and Hamden’s legislative town council. Medina Camiscoli said the group will be meeting at the end of February.

“For me, the work of the Hamden School Diversity Council is really thinking about how we acknowledge the history of what racism and inequality is in our society, how that manifests in many different layers,” she said.

As the meeting neared its close, several attendees expressed frustration that their concerns had not been addressed. Cassi Meyerhoffer, an assistant professor of sociology at Southern Connecticut State University, called for more accountability from the committee and the board of education.

“We started this [meeting] talking about urgency for systemic change,” she said. “And then we spent the last two hours patting ourselves on the back, and our schools are still segregated!”

Kathleen Kiley, who is a teacher of color at Ridge Hill School, noted the lack of resources accessible to her. She noted the amount of time that has disappeared from her schedule—in recess breaks that she must supervise, half days that have disappeared, and parent-teacher conferences that are now condensed—as she and her colleagues are constantly asked to do more with less.

If the district truly supports equity work, she suggested, it needs to put the proper funding behind it. She said that she felt particularly pained speaking Tuesday, because the teacher who had turned to the Scholastic play had done so after complaining in a staff meeting that she did not have adequate material in her classroom.”

“Culturally responsible professional development is not the same as giving teachers content to teach,” she said. “We are trying to do way too much.”

“Yes, students of color need teachers of color,” she added. “But so do white students.”