Politics | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Yale Center For British Art | Yale Prison Education Initiative

| James Jeter, Zelda Roland, Randall Horton, Lauren Baosso, and Peter Wicks and the panel. During the talk, Horton—a professor at the University of New Haven who is also a former prisoner—called prison “a morally bankrupt system that would never allow a zero balance.” Karen Marks Photo. |

Zelda Roland has this story. In a juvenile detention center not so far from Yale, students are preparing to take university-level art classes provided by the university. There’s acrylic painting, charcoal drawing, other mediums. Roland overhears the guards call out for “Yale finger-painting!” And yet the center’s students make their way to the classroom, sitting down with their materials and getting to work.

Roland is the director of the Yale Prison Education Initiative (YPEI), a program through Dwight Hall at Yale that offers Yale courses to incarcerated students in Connecticut. Friday afternoon, she brought that story to a public panel on prison history and education held at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) in downtown New Haven. Part of a day-long colloquium for the exhibition Captive Bodies: British Prisons, 1750–1900, the panel sought to connect the legacy of the British penal system with the American prison industrial complex.

The exhibition, which opened at the end of August, runs through Nov. 25. It is curated by Courtney Skipton Long, a postdoctoral research associate with the YCBA. YPEI, meanwhile, brings Yale college classes with credit and Yale College transcripts to prisons. The program launched in May.

As the public portion of the program began Friday afternoon, Long gave attendees an overview of the Captive Bodies exhibition, beginning with prints and paintings of British prisons as far back as the 18th century. In one image, a 1761 drawing by Giovanni Piranesi depicts the British prison before bars and columns—the open space is dark and there is no escape for inmates. Prisons were a theme for the artist: his Italian “Carceri” (“Prisons”) etchings, largely figments of his imagination, stoked fear and wonder in viewers, who were left wondering about the insides of buildings they might never see.

“Prisons are about fear and power,” Long said.

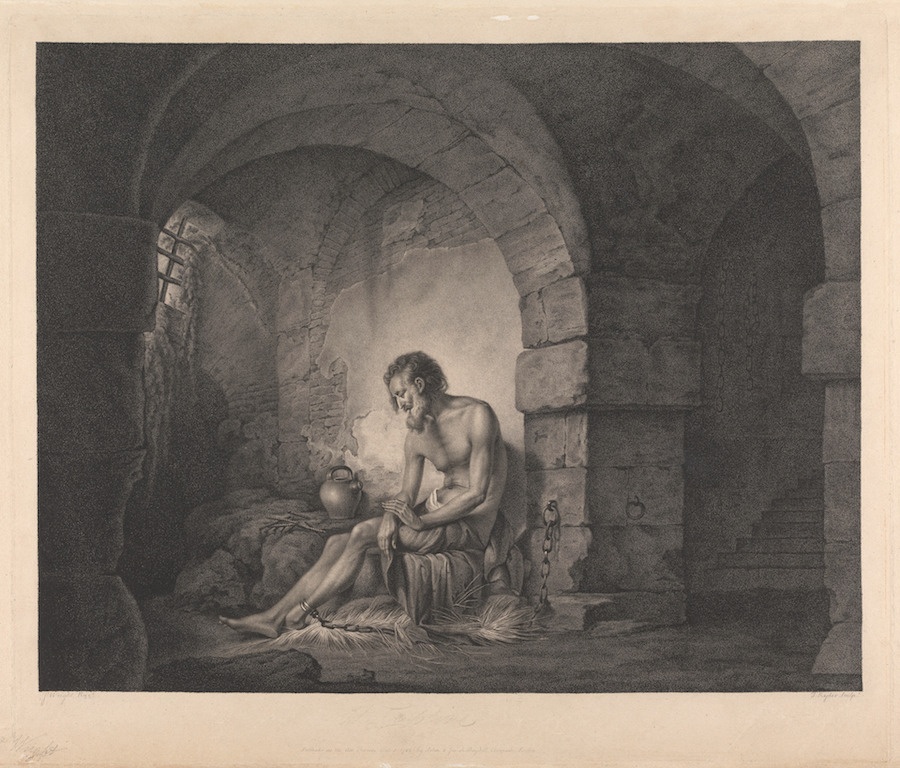

| Print made by Thomas Ryder, after Joseph Wright of Derby, The Captive, 1786, etching and stipple engraving on paper, Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. John E. Larkin Jr. in honor of Jules D. Prown. YCBA Photo. |

In the exhibition, that power is extended in Jeremy Bentham’s 18th century “Panopticon,” an architectural rendering (and, in a sense, proposal) for what scholars once thought was the most effective prison of the period. In the panopticon, prisoners are arranged into individual cells along columns extending from a central watchpoint where a single guard can watch all prisoners at all times, without them seeing him. Those in a panopticon-style prison would always know they were being watched, without being able to see or face the source of their surveillance.

This carceral history is a relic of the past, until it isn’t. As Long showed in her presentation, many prisons of this and other styles are still used in the United Kingdom today. Long highlighted one prison built by a Brit in 1821 in Philadelphia — the Eastern State Penitentiary, now open to visitors as a famous historic site. Long called it a “conscious site,” recalling her tour of grim hallways and crumbling cell-blocks. It has capitalized in that history, becoming a haunted house with themes that range from “Break Out!” to “Quarantine (4D).” The Eastern State Penitentiary closed operations as a prison as recently as 1971.

“When I think about prisons, the images in my mind came from film and TV … and prisons are such a large part of the American experience,” said panelist Peter Wicks, a professor pf philosophy at Villanova University and scholar-in-residence at the Elm Institute. In these settings, he added that prisons are still considered a form of rehabilitation despite prisoners’ environment of constant surveillance and dehumanization.

Wicks described the process of teaching a class in prison. He arrives early in the morning to meet a prison guard, instead of arriving to a lecture hall just in time for class. After going down a “quarter-mile long corridor,” he meets another guard who brings him to the classroom where his students, who have been similarly escorted, meet him. He can’t bring coffee to sip throughout class. If he wants a marker or eraser to write on the board, he has to go back to a guard who will provide him one. When the books he ordered to teach his students about Homer did not pass clearance fast enough, he had no choice but to skip ahead to Plato.

“The environment is very outside of my control … this was a program that could be taken away,” he said.

| Zelda Roland. Karen Marks Photo. |

Still, Wicks said he considers his students the “ideal constituency for a liberal arts education.” Despite their imprisonment, his students were not “semi-coerced” into taking his philosophy class in the same way his Villanova undergraduates are required to do to finish core requirements. But they, too, deserve the same scope of career possibilities after release.Lauren Boasso, a lecturer at the University of New Haven, recalled learning that her college ordered cheap dorm furniture made by prison labor every year, effectively buying into the manual labor and “shop” classes that some prisons provide as their only option for education.

Roland said she believes that accrediting these liberal arts classes in prisons will give them the same value in the outside world as vocational skills. Since it launched in May, Roland has offered the Yale English classes “Reading and Writing the Modern Essay” and “Readings in American Literature” to one of the largest maximum security prisons in the Northeast.

“600 people signed up,” she recalled.

Because Yale English classes are seminars of about 12 students, Roland and her colleagues had to run interviews to turn 600 potential students into 12.

Still, Roland said, some prisoners enjoyed the process. “Due to their ages of entry, it was the first program they’d ever applied for.” For those with sentences that would take them into old age, Roland suggested it might be the only application and interview process they will ever go through.

YPEI Fellow James Jeter spent almost two decades in prison, from the time he w17 to the age of 36. He was able to complete his General Education Degree (GED) and take accredited college classes with credit through a Wesleyan prison education program.

Once Jeter was released and began applying to colleges, he found that the best way to overcome the bias he found from admissions committees was his transcript. A high GPA got him off the Trinity College waitlist and gave him an opportunity to attend college. He said he believed that he would now have had that opportunity had the classes been without college credit.

“A lot of my education was reading and writing and arguing,” Jeter said, laughing in a response to a question about the quantitative value of a liberal arts education. “So my work as a policy analyst was also a lot of reading and writing and arguing.”

Captive Bodies: British Prisons, 1750–1900 runs through Sunday, Nov. 25 at the Yale Center for British Art. The center is open Tuesday through Sunday at 1080 Chapel Street. For more, visit the YCBA's website.