Audubon Arts | Black History Month | Creative Arts Workshop | Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Arts & Anti-racism

Detail, Jasmine Nikole, “The Present Is The Future.” Made Visible: Freedom Dreams runs at Creative Arts Workshop through March 18. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The woman is running beneath a wide open sky, a sheaf of sunlight on her face. Her eyes look out to the horizon; her arms rise and fall as she moves. Behind her, rows and rows of cotton stretch into the distance. The bolls sway and swell against the wind, some splitting open. They rise past her hips and branch out onto the wall.

Everywhere, the past slams right into the present. As it unfolds, the future seems stunningly, startlingly bright.

She is part of Made Visible: Freedom Dreams, running in the Hilles Gallery at Creative Arts Workshop (CAW) through March 18. Curated by nico wheadon in partnership with the bldg fund, llc, the exhibition features work by artists Linda Vauters Mickens, Jasmine Nikole, and Y. Malik Jalal. It includes programming from Inner-City News Editor and WNHH Radio Host Babz Rawls-Ivy, who has installed work in a corner of the second-floor gallery.

The exhibition draws its name from Robin Kelly’s eponymous book, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, a copy of which is featured in the exhibition. It also marks the fourth iteration of the Made Visible exhibition series, which CAW launched in mid 2020.

nico wheadon: “It feels like a really important moment for artists to reclaim center stage and the conversation around what we want our culture to look like and how we want institutions to support that.”

“This has been three years in the making,” said wheadon, who moved to New Haven four years ago, at an opening Tuesday night. “It’s really just a look at how artists see the issues of our times, but also like, what we might do to change things for the better.”

The seed for Freedom Dreams sprouted years ago, and has been steadily growing in wheadon’s mind and curatorial eye since then. In her personal life, wheadon and her partner, bldg fund co-founder Malik D. Lewis, have been talking about what it means to freedom dream “really since we got together,” she said Tuesday. It has since taken many forms, from her book Museum Metamorphosis to her young son Nile, who is just over a year old.

Then last February, she was able to explore “what it meant to look at artists’ visions for the world and how we might change it to better reflect us” more deeply while curating a show at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz. It was a short show, she said, and she left wanting to bring the same line of questioning to New Haven. The artists she selected do exactly that, at a moment when several of the city’s arts organizations find themselves in transition.

“You know, it’s been a tough moment for New Haven,” she said Tuesday. “There’s a lot of arts leaders that are no longer here, or leading these institutions, and so it feels like a really important moment for artists to reclaim center stage and the conversation around what we want our culture to look like and how we want institutions to support that.”

Linda Vauters Mickens, "Redemption."

What makes the show so moving is that the artists—who range from a first-year graduate student at the Yale School of Art to a retired nurse to a self-taught painter with two children under three—are in constant dialogue with both their viewers and with each other. Even before a viewer enters the gallery, Jalal’s work is a part of their sightline, with an ode to Black New Haven that runs decades deep.

On CAW’s street-facing windows, the artist has enlarged a series of family photographs from IfeMichelle Gardin, a lifelong New Havener who is now the founder of Elm City LIT Fest. In one image, a baby sits in an inflatable pool of water, looking up at the camera. Their tiny mouth is a wide, curious O. Above them, two elders embrace, a rose garden rising in the background. In front of them, Audubon Street is a sprawl of cement and asphalt. It sets a tone that is at once historic and very present, archival and familiar.

Over two floors of the gallery inside, wheadon has drawn that tension out, balancing both the bitter and the sweet of freedom dreaming. While one of Mickens’ angels welcomes viewers into the space, it is her 2022 “Redemption” that pulls a body into the room with nearly umbilical force, glowing bronze and gold beneath the gallery lights. Placed just beyond the center of the gallery, the sculpture turns her whole body to the left, her eyes squeezed shut. In her hands, she holds an assault rifle, her index finger on the trigger. Above it, her mouth opens in the wide, pained O of a silent scream.

Detail from Linda Vauters Mickens' "Reflections" (2021-2023). In an accompanying description, she has written: "Her wings are shaped by four figures-two bent and stooping from the weight of labor [and] two standing tall despite their exhaustion."

Her garments, which cling to her small and strong body, build a collage of names and faces that seem unending, sometimes cut off before a viewer can get a full sense of a full word. Nails—dozens of them, maybe hundreds—protrude from her skull, building a sort of barbed and armored crown. The mirror image of the word Knowledge, written in all capital letters, scrolls across the base of the milk crate she sits on.

Just over her shoulder, Mickens’ “Mother As First Teacher” feels completely of a piece with this tableau. In a single, pained moment, these women hold centuries of history, more resilient than they should ever have to be. They are Black women who deserve rest more than anything in the world, and instead must continue to fight in battle they never asked for, and didn’t start.

“Redemption dreams of the day when the mission has been complete, victory claimed and her well-deserved rest has been received,” Mickens has written in an accompanying label. “The day has not yet arrived, and so, Redemption marches on, ever fighting, never resting until her work is done and her people are free.”

Top: Detail, "Reflections" (2021-2023). Bottom: The artist Tea Montgomery looks at Mickens' "Cross" (2022) on opening night.

Beside it, a swath of heavy, thick red velvet drapes over a cross, synonymous with the bloodshed of Jesus Christ before his resurrection. In a sacred context, it recalls the suffering of Jesus, in a form a church-goer might see during Holy Week. But Mickens has gone much deeper, peeling back the layers of Christianity to reveal something rotten underneath. That she has chosen a red cloth—rather than purple, or black, or white—feels heavy. It’s a symbol of Christ’s pain, which here becomes the pain of generations of Black people.

On the wooden body of the cross, Mickens has painted incomplete American flags, wrapped rope, hammered in nails and shackles and added the text of “Strange Fruit,” the anti-lynching song that Billie Holiday first made famous in 1939. Taken together, it signals the abuse of Christianity as a tool of white supremacy and a disenfranchisement of Black Americans that continues today. It is powerful and arguably overdue in CAW, a secular space that has only in recent years begun to reckon with its own history of whiteness.

wheadon’s curatorial eye is agile: a viewer can and should study it from the first floor gallery, but it’s also worth looking at from the second floor, which gives a bird’s-eye view.

Mickens' "Cross" (2022).

In this sense, Mickens’ work is an anchor and a spatial core of the show, reminding any visitor why the concept of freedom dreaming needs to exist in the first place. Beyond her “Reflections,” a multi-part installation completed over the past two years, Jalal’s enlarged photographs pull a viewer back into the building’s lobby, and towards a second gallery upstairs. In the hallway, photographs beckon in every direction, hovering over the guest book and welcoming visitors in the foyer.

It’s a teaser for the second-floor gallery, where the exhibition continues with work from Nikole, Jalal, and Rawls-Ivy. Along one wall, Nikole’s four-part “The Present Is The Future” draws a viewer in close, telling a story over four vibrant narrative panels. In the first, a woman runs forward, her chest out, a city skyline receding in the distance behind her. Over her shoulder, rows of cotton stretch across a field. “Her ancestors [are] in the back, kind of ghost-like,” Nikole said Tuesday.

In the next three panels, Nikole has told a story that makes time feel bendable and porous. First, her protagonist’s ancestors teach her to cultivate the earth, holding a younger version of her as she looks out of the frame, and towards the viewer. Then, she is the one teaching, still looking out of the frame as plants spread their marbled leaves around her, and three other figures lovingly tend to the earth.

Detail, Jasmine Nikole, “The Present Is The Future.”

In the fourth and final canvas, Nikole has imagined ahead into the future, a whole society built around cultivating the earth. On the right, one of the figures rests her hands on her pregnant belly, signaling future generations. Around and between each canvas, Nikole has painted the white wall, creating a mural that feels organic and alive. “They’ve reached freedom,” she said.

“The cotton plant is such a beautiful plant, but it holds a lot of pain,” she added. “Everything [here] revolves around nature—getting back to what we used to know and living our true authentic selves. It shows her past, present and future all in the same picture.”

For the artist, who grew up in New Haven, the series and the exhibition are dreams realized. As early as kindergarten, Nikole can remember loving visual art so much that she began teaching herself to paint from a young age. When she graduated from high school, her parents urged her to “find something more lucrative” instead of painting, she said. She had always been good at math and science, and chose engineering.

She was working as an engineer and pregnant with her first child in 2020 when Covid-19 hit, and the world shut down around her. The isolation took a mental toll, she remembered—and art was there as a therapeutic outlet. In 2021, “I decided to take a leap of faith” and jumped into her artwork full time. Two years later, she’s building a practice around it.

“Here I am,” she said.

Y. Malik Jalal, "Stay Out the Way" (2022). The photo is from the family collection of IfeMichelle Gardin.

On all sides, Jalal has selected photographs of Gardin’s family members, giving current viewers an intimate and deeply affecting window into the city’s past. On one wall, Gardin’s cousins Jaryn Travers and Jason Goodson are young kids again, posing in their dance costumes as huge smiles burst across their faces.

When the photos were taken, both were students at Ms. Dee Dee’s Dance Studio when it was still on Fitch Street. Now, Travers is a human resources director at Sikorsky. Across the room, a photo of Gardin’s late grandparents, Eugene and Annie Huckaby looks out from the wall, frozen in time. A few feet away, her nieces stand hip-to-hip in oversized pajamas for Disney’s The Little Mermaid. Jalal’s “Stay Out the Way,” a scalloped cast iron frame that surrounds it, feels right on time.

These dreams—the sense that the future is possible and bright, and also here—continue all the way through the end of the show, where Rawls-Ivy has recreated something that is half front porch, half-living room. In an alcove across the floor, she has installed a bench with beaded angel wings, and shelves of flickering candles, beads, old postcards, and personal items that are dear to her. One of Susan Clinard’s boat sculptures peeks out from the corner.

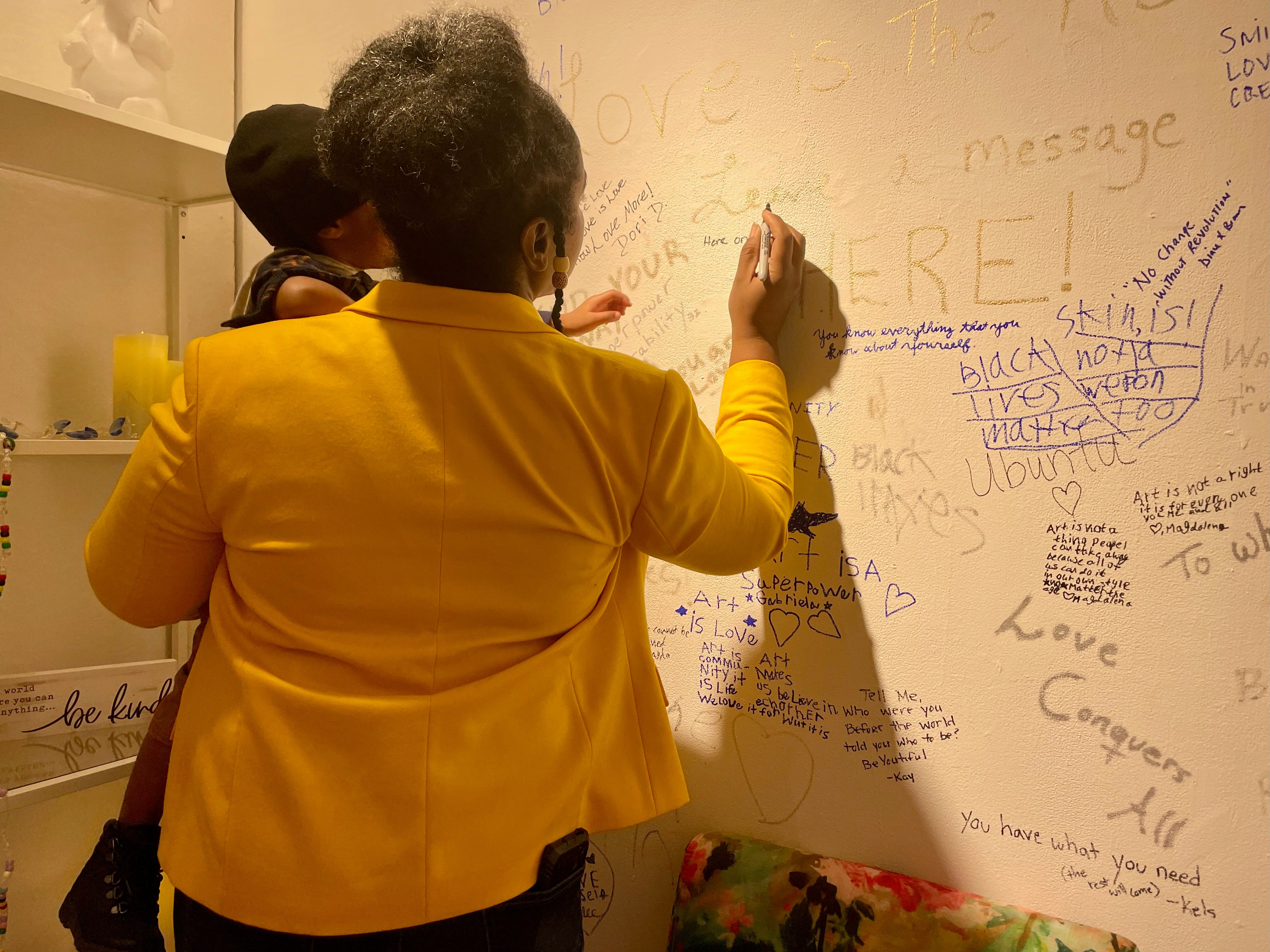

Jasmine Nikole with her son: Here on Purpose.

On a slice of wall, she has invited attendees to reflect on what freedom dreaming means to them. Tuesday, Nikole lifted her young son onto her hip, and spelled out the words “Here On Purpose.”

“Being able to come and sit with someone in a moment when we’re all isolated, in and of itself, feels like a really powerful thing,” wheadon said Tuesday night, “And that it’s Babz is even more powerful. So all those four elements together feel like a conversation that’s unique to our city.”

In the exhibition, her words echo over every square inch of the gallery, making it to the outside of the building and out onto Audubon Street. In the year 2023, maybe Made Visible: Freedom Dreams should not feel as radical or overdue as it does. And yet, it exquisitely takes up space in a building that has spent six decades not making room for Black people.

In that sense, Freedom Dreams is also a call to action: it cannot be a one-off, in a city that has trumpeted a commitment to cultural equity, then continued to underfund it. It is a call for CAW and like institutions to showcase, compensate, and amplify artists and curators of color all year round, not just during February. Whether the organization will choose to do so as it goes through a leadership transition remains to be seen.

IfeMichellw Gardin points out figures in the photo to Markeshia Ricks (in the red coat) and Babz Rawls-Ivy (in the white coat).

As night fell over the street Tuesday, Gardin pulled a group of friends outside to point out siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles, parents and grandparents who now felt close enough to touch. In one photo, enlarged to the size of a small billboard, her brother Michael posed in front of a white fire truck, the words Engine 17 emblazoned in gold lettering. The words New Haven peeked over his shoulders at the center.

Beside it, a little girl at the bottom opened her mouth and smiled, laughing as the shutter clicked. It was Gardin’s mother, Elnora Huckaby Gardin, as a little girl in the Elm Haven projects decades ago. Gardin loves the photo, she said: her mother, who was not often happy, seems for a moment overjoyed.

“Seeing the pictures, it’s surreal,” Gardin said. “I never saw them as art because they were my family. My people.”

Curated by nico wheadon in partnership with the bldg fund and Babz Rawls-Ivy, Made Visible: Freedom Dreams runs at Creative Arts Workshop through March 18. Join Rawls Ivy in the upstairs galleries Mondays 3-5 p.m. February 13 through March 6 or on February 25 from 1 to 3 p.m. Creative Arts Workshop is open 9 a.m. through 7 p.m. and Saturday 9 a.m. through 4:30 p.m. For more information visit their website.