Education & Youth | Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | Truman School | Wilbur Cross High School | COVID-19 | Education

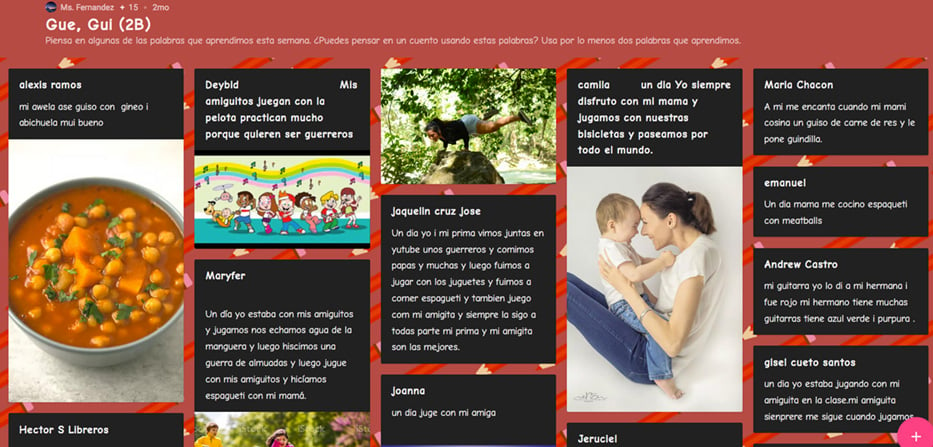

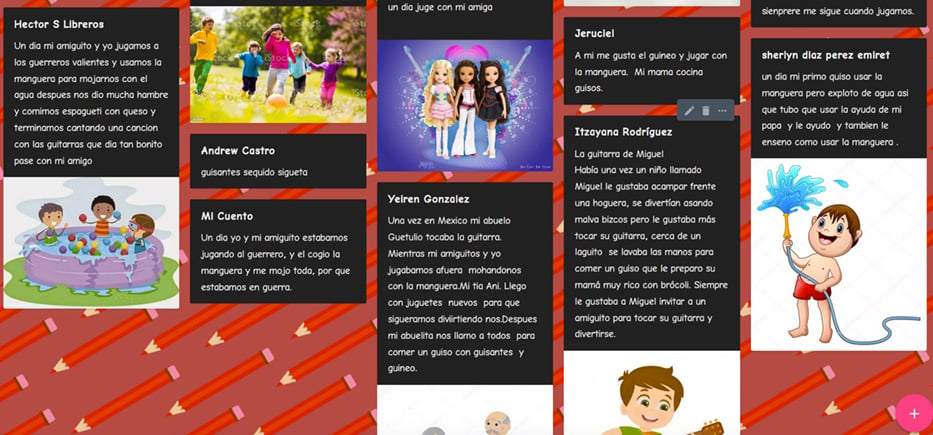

A screenshot of classwork from Carolina Fernandez's bilingual class. Picture courtesy of Carolina Fernandez.

A screenshot of classwork from Carolina Fernandez's bilingual class. Picture courtesy of Carolina Fernandez.

Amna wakes up her four kids at 7 a.m. to get them ready for school. Until recently, all of them went into separate rooms to log onto classes from Conte West Hills Magnet School. Every 30 minutes, she checked on them to make sure they were all on track. Now, she makes sure that they all get the bus on time and have their hybrid schedules right.

Meanwhile, Amna is busy too: she attends English-Language Learner (ELL) and computer classes as part of a fellowship program from Havenly Treats.

Amna is one of hundreds of immigrant and refugee parents across New Haven who have struggled with remote and hybrid school during the pandemic, as English language learning becomes harder to navigate over spotty internet connections, a shortage of laptops, and difficult home environments. Over a year into the pandemic, she is working with educators to find a better solution.

“They are at home all the time and are only around Arabic speakers,” she said in a recent interview. “The TV’s in Arabic that they watch cartoons in Arabic, they talk to each other in Arabic. They've lost the opportunity to be exposed to English.”

Non-English speaking immigrants, especially more recent ones, face particular challenges in adjusting. Amna, for instance, knows that her second grader Halima likes to log off classes a little early. She and her younger brother, Mustafa, struggled the most adjusting to remote learning, and are now struggling to get back to hybrid. Halima was no longer taking ELL courses, but after falling behind in her English class, ELL coursework was introduced back.

Bahati Kanyamanza, education manager at Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS), described challenges including a lack of space and difficulties with technology. The organization helps incoming immigrants and refugees with resettlement, legal aid, and educational services including English language training. After Amna left Sudan in 2014, IRIS helped her transition.

The pandemic has created a number of extra hurdles for the organization, which was already fighting slashed federal funding and historically low refugee admissions under the Trump Administration. Last summer, approximately 100 school-aged children attended IRIS’s 12th annual Summer Learning Program to improve their English and math skills online. The program is traditionally in person—previous summer sessions have been held at Wilbur Cross High School. In June 2020, the program went virtual due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The program is often a critical step for recent arrivals, Kanyamanza said, because most of the children have had gaps in their education. This happens for a variety of reasons, but among the most common are constant moving and a lack of resources. In some cases, students have gone as long as four years without any formal education. Depending on the child, it can take months or years to make up the gap.

IRIS has been teaching its after school classes virtually for over a year.

The first day of the program, only 20 students logged in. Immediately, staff and volunteers jumped on the phone to figure out what went wrong. Most of the families did not know how to log onto the computer or Zoom.

“Now boom they [students] are supposed to learn through technology and these different platforms, Google classroom, Zoom, and all of these other resources with no introduction,” Kanyamanza said.

Similar issues arose once the current school year started. Amna’s children struggled with their school-provided computers and tablets early on. Another family had done well during the summer program, but didn’t understand the schedule their child had received from a school. Kanyamanza did a home visit to show the family how to transition between virtual classrooms.

On the same visit, he happened to spot five high-school age students on their laptops, working inside a turned-on car. None of them had their masks and not all of them lived together. That’s not uncommon, said Director of Community Engagement Ann O’Brien. Most families have to wrestle with a lack of space, and most have complex living situations. Many families live with extended family members or other families in the same residence.

“There's one example where there I think there were six kids in a two bedroom apartment … all trying to connect but the noise is so much that the three of the kids took one of the Chromebooks and went to the car,” she said. “The lack of space is an issue, the technology, and then the language barrier, right?”

Even once IRIS thinks a family’s issues have been resolved, it isn’t uncommon to get a call from a school asking why the students haven’t shown up to class. O'Brien attributes it to children being resistant to remote learning and having a better grasp on technology than their parents. The child might be on the laptop and say they’re logged onto class but log off once the parent leaves the room.

She said she worries that some students are falling through the cracks. Prior to the pandemic, volunteer tutors would meet with students during the school day and provide one-on-one tutoring for English and math. According to teachers, students were able to jump two or three grade levels in their English skills through tutoring, compared to students who did not have access to the tutoring service. IRIS has continued after-school activities online.

“It is just an incredible shame for these kids, because they've lost so much schooling already,” said O'Brien.

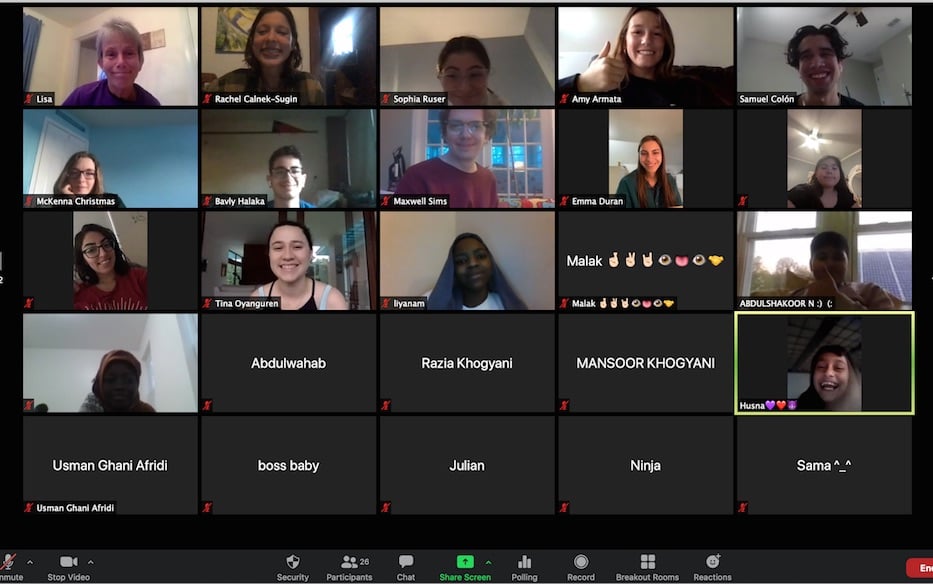

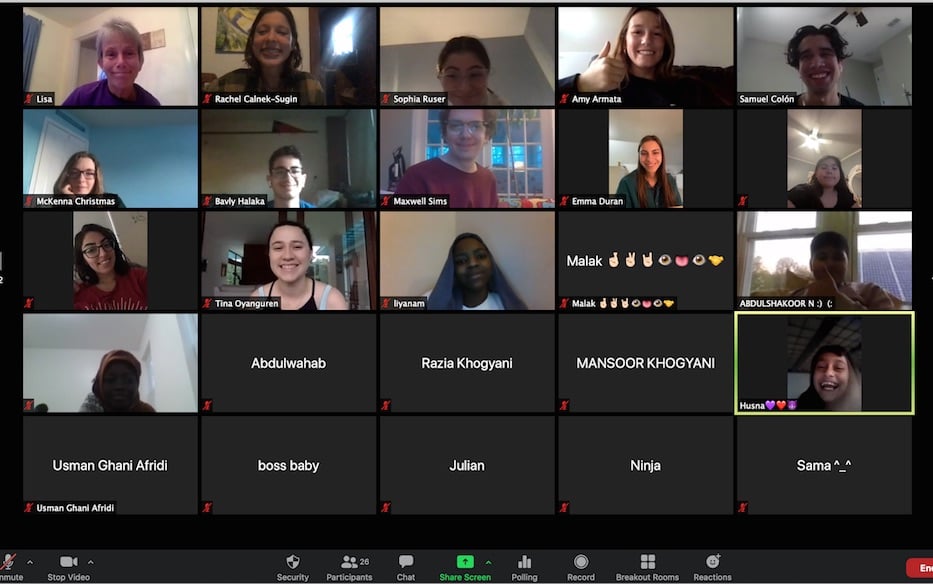

A screenshot of classwork from Carolina Fernandez's bilingual class. Picture courtesy of Carolina Fernandez.

A screenshot of classwork from Carolina Fernandez's bilingual class. Picture courtesy of Carolina Fernandez.

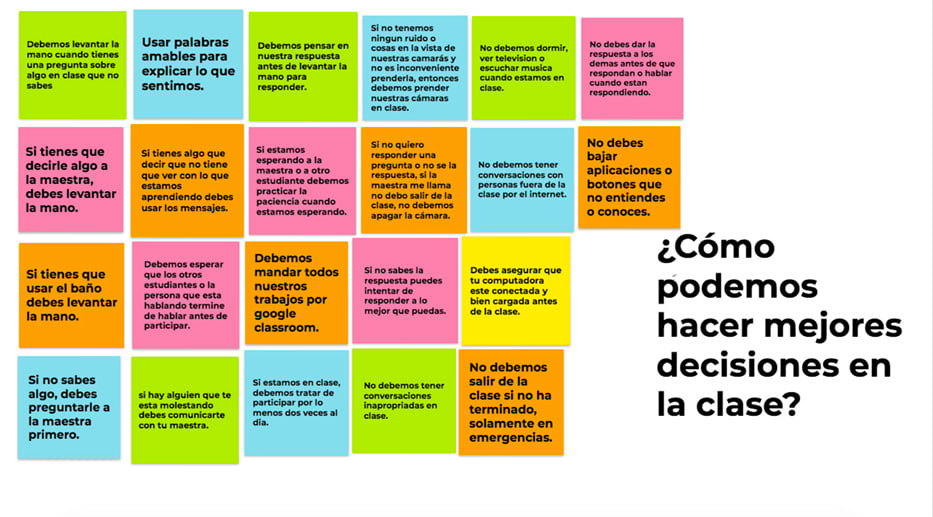

Carolina Fernandez, a second grade bilingual teacher at the school formerly known as Christopher Columbus Family Academy, quickly learned that she needed to find a balance between meeting benchmarks and engaging with her students. As part of the bilingual curriculum, she alternates teaching in Spanish and English on a weekly basis.

“I have been focusing on the motivation and the willingness to come to school for this year,” she said. “We have learning goals, but the most important part is to keep students interested and motivated to come to school.”

Her lesson plans vary widely from week to week to keep the students as engaged as possible. She might open class with examples of alliteration in Spanish—Lunes, Lima, Miercoles Melon, Jueves, Jalapeno. Another day the students might sing Corazon de Melon, a song about fruits. Another day, she’ll read a book to them.

Her PowerPoint presentations are dotted with emojis and the digital worksheets have vibrant patterns, things she couldn’t have done as easily in person. From her perspective, if the work can emulate the fun digital content students seek out on their own time, they’ll be more likely to engage.

So far, it has been working. She said that the overall participation rate hovered around 80 percent for fully remote instruction. Since schools returned to in-classroom teaching, roughly 60 percent of her students have returned to in-person instruction.

She attributes most of that success to the relationships she built with students and families prior to remote learning. She used to wait with students who got picked up at school and meet with parents then. Those interpersonal relationships translated well to remote learning— parents reach out to her often.

While she’s mindful that standardized testing and assessments remain a significant part of the curriculum, she’s focusing on those relationships.

“Learning goals are important but we're not pressuring them to reach their highest level like in-person because that isn’t reasonable,” she said. “We don't want them to feel discouraged and not come to school. We want them to do really well because they want to come to school.”

A screenshot of classwork from Carolina Fernandez's bilingual class. Picture courtesy of Carolina Fernandez.

A screenshot of classwork from Carolina Fernandez's bilingual class. Picture courtesy of Carolina Fernandez.

Teachers across the district see internet connection and a lack of space as constant problems. Truman School teacher Ryan Heath has worked with families to qualify them for subsidized internet programs targeted towards low-income families. He had success signing up some families for Comcast Essential, a subsidized internet service that charges $9.95 per month for families that typically qualify for SNAP or Medicaid.

Other families fall to the wayside for one reason or another, he said. Some are disqualified for having already had an existing account with Xfinity within the 90 days. Others, because they might have an outstanding debt to Comcast. The program does not require a social security number, but, it does require additional proof of identification in lieu of it. Beyond the programs, some of the families have mixed legal statuses or choose to stay off the grid.

“A lot of the families that I work with rent under the table in cash, and their name might not be on a lease or the gas bill,” he said.

Even if the students do have internet access, it is often slowed down because multiple families or generations might live in the same residence. It isn’t uncommon for four of five children in a residence to be in class simultaneously, dramatically slowing down the bandwidth for all of them. However, often the students find ways to work around.

“They're like logging on and they'll be like, ‘Gosh, so sorry! I’ve had trouble all day long. So I went downstairs I'm sat on my porch outside the neighbor's house. They said I can use their internet.’ For me, that's enough. That's putting gas in my tank for sure,” he said.

Despite the challenges, there have been some highlights. Throughout the year, Heath integrated a series of virtual events ranging from careers talks with doctors and pilots to tours of restaurants. Over a Zoom call, Dr. Giovanna Guerrero-Medina, the executive director of Ciencia Puerto Rico (CienciaPR), spoke to the class about her relationship with bilingualism and her research. Through CienciaPR, she works on contact tracing in Puerto Rico and vaccine research.

Ryan Heath flying a plane.

Ryan Heath flying a plane.

On another call, Heath flew a plane at the New Haven Aviation School and brought the students along with him virtually. He attributed much of the success to working with retired New Haven teacher Cameo Thorne and leveraging his connections in the community.

“I think for those kids it was like it made it real for them,” he said. “Like, we can do this, like we it's here there's access, you know, and I think that that's part of access is like showing them like there are people out here that want to help you.”

While the chat often explodes with excitement, he rarely gets to see students’ real time reactions. By Connecticut law, students are not required to turn on their cameras.

He’ll ask students to show their work on camera or show their faces for participation, but most opt for the chat. One student, for instance, had a particular aversion to turning on her camera. He met one-on-one with her to see if there was a reason for keeping the camera off. She didn’t share anything. Later, he learned that her grandmother had passed away.

“It's hard to measure how students are doing because you can't see their faces,” he said. "I think that’s the toughest thing about it because part of the job is to check in on them.”

Roughly 90 percent of students stay throughout the day. With the option of the hybrid model, roughly 80 percent of his students have returned to the classroom.

Heath preparing to race cars with help from the students.

Heath preparing to race cars with help from the students.

The issues faced by some ELL students get more complicated with age. Kristin Mendoza, an English teacher at Wilbur Cross High School, said that new part-time jobs have made learning harder for many of her students. She works primarily with juniors and seniors. At Wilbur Cross, 412 students out of 1547 students were expected to return at the beginning of the month. In early April, that number was only 203.

While the district distributed thousands of Chromebooks at the beginning of the year, Mendoza said that computer and internet access remains a constant problem. There isn’t a day that goes by without troubleshooting a locked account or poor connection. She said that the school is very responsive to these issues, but they remain constant.

She’s also found that the biggest barrier to student participation is economic insecurity. A number of her students have either picked up part-time or even full-time jobs to help supplement their family’s income. Some of them work at the Amazon warehouse in North Haven; others at restaurants or construction sites. As work schedules overlap with classes, she sees grades gradually falling.

“We have a lot of conversations about ‘how do you approach your boss if you want to get your schedule changed?’” she said. “Can I have my schedule start at 2:30 p.m. or whatever the change needs to be.”

Like other teachers, she doesn’t get to see many of her students, or have some of the same conversations she used to. In person, her homeroom class was all Spanish-speakers. Students who had recently arrived in New Haven were grouped with students who had lived in the city for a while. Those 20 minutes they shared were a home base where they could connect in their first language, said Mendoza.

These types of interactions are beneficial for the newer arrivals who can rely on their peers for help. In particular, she has a few students from Central America and Southern Mexico who have had interrupted formal education stopping around elementary school. As a result, some of the students never developed strong study skills or academic strengths in their first language meaning they can’t transfer those skills to their regular coursework. Even during synchronous class it is hard for them to participate and know how to attend school.

She’s worked closely with families trying to resolve internet issues, but has run into dead ends. Sometimes, two or three families live in an apartment, each with their own bedroom, and all depend on the same internet source. After the internet was shut off for two students' families, she tried to help them apply for Essential Comcast. They were ultimately denied because the address was already in use.

She also worries about technology’s integration for the sake of technology. She recognizes that some students are dealing with anxiety and depression from multiple directions during a time of peak isolation, she said.

“Technology is so vital and so useful but it does not replace real interaction with real people,” she said. “As much as we need to fight for equitable access to technology and better access for everyone, I don’t actually see that as a real solution to what’s going on.”

“I just think how hard it is to be a teenager and not be able to do normal teenager things,” she added. “It's very hard to find the motivation to keep logging in every day I think for them without that social aspect.”

If pandemic has tested the limitations of remote learning, it may also have a silver lining, suggested Elizabeth Howard, associate professor of bilingual education at the University of Connecticut. It has solidified certain practices, such as in-person cooperative learning, as essential to bilingual education.

“Cooperative learning is, you know, major, major strategy for bilingual learners, because it gives them chances to talk a lot and listen a lot in low stakes environment, we're going from other students so it's not just the teacher that they're hearing talking that they're able to navigate things with their small group so they have to step up and talk more.”

At the same time, staying at home with grandparents, aunts, and uncles has allowed children to develop even stronger language skills in their first languages. Often, ELL courses put such a strong emphasis on learning English to a high language that other languages are neglected, she said. That means losing important histories. Additionally, strong language skills are transferable between languages. It is beneficial in the long-term to develop both languages as much as possible.

As for the general direction of the field, she believes that multiple directions have opened up that previously might not have been considered as heavily. For example, she believes that technology will be incorporated further into in person lessons allowing more flexibility with pacing. Students could potentially record themselves practicing diction on their own time, or access created materials on their own time.

Over the last months, she has seen a boom in online resources that are shared among educators in Google classrooms or Facebook groups. As a result of not having a centralized standard for remote learning, educators were forced to create their own virtual libraries through trial and error. She’s also seen more incorporation of multicultural and anti-racist literature in these self-curated resources.

There are also opportunities for parents and extended family to contribute to these online libraries especially for languages that may not have as many resources available.

“It isn’t hard to find Spanish videos, but what if you have Bengali speakers in the class?" she said. "You can ask their parents to record a video of them reading in Bengali and upload it to a digital library. Even if the family doesn’t have strong literacy skills, they could tell stories and share their rich oral traditions. Technology really affords people to be able to contribute in meaningful ways.”

This shift to self-curation could also mark a shift in less centralized curriculum across the state. Often educators are given a curriculum with flexibility. The pandemic allowed educators to develop best practices for their own students tailored to their students’ cultural backgrounds.

“In a way the pandemic has opened up the possibilities for more teacher professionals and the teacher autonomy and creativity," she said.