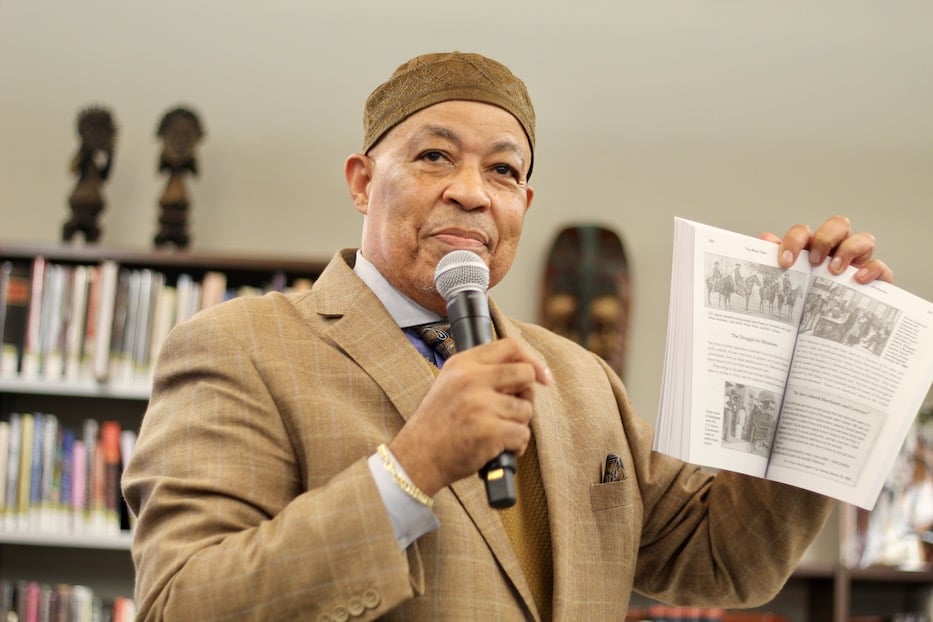

Judge Clifton Graves and composer Joel Thompson. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The first time composer Joel Thompson read James Baldwin’s “To Be Baptized,” he could feel the words rattling through him. If one really wishes to know how justice is administered in a country, one does not question the policemen, the lawyers, the judges, or the protected members of the middle class, Baldwin wrote. One goes to the unprotected — those, precisely, who need the law's protection most! — and listens to their testimony.

It was 2021, or maybe it was 1972, or maybe somewhere in between. Thompson let himself read and re-read the words. From the page, Baldwin urged his readers to ask “any Mexican, any Puerto Rican, and Black man” whether America was just. The sentences stayed with Thompson as he sat down to compose, as he listened, as he made stops around the country to present his work. Always, they were as prophetic as they were troublingly timeless.

Thompson, a soft-spoken, musical dynamo who is the 2022-2023 composer in residence with the New Haven Symphony Orchestra, will bring those words to the John Lyman Center for the Performing Arts this Sunday, for the New England premiere of his work “To Awaken The Sleeper.” The piece, written last year, layers Thompson’s composition and Baldwin’s text in an incisive, stunning critique of white supremacy in the United States.

It marks a continuation of his work as a platform for social justice, from his sweeping 2015 “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed” to his 2019 “In Response to the Madness” and 2020 “breathe/burn: an elegy,” written in memory of Breonna Taylor. Last Wednesday, he joined Probate Judge Clifton Graves at the Stetson Branch Library on Dixwell Avenue to discuss the piece, his second composition in two years to use Baldwin’s text as a launchpad.

Dee Marshall, who is a longtime educator in the New Haven Public Schools system. Lucy Gellman Photos.

“There was a joy working on this piece,” Thompson said in the library, as BAMN Books sold copies of Baldwin’s fiction and nonfiction in the back of the room. After writing the Baldwin-inspired “My Dungeon Shook: Three American Preludes” in 2020, “I knew there was so much more that he had to say, and I knew that I could use the bully pulpit that I have as a composer to amplify his voice … Like Baldwin, I’m trying to use this platform to will the world I want into existence.”

Thompson’s path to the piece began years ago, when he discovered Baldwin’s writing as a student at Emory University in Georgia. At the time, Baldwin became “sort of a guiding light” in his young life, he told the Arts Paper in an interview earlier this year. What stayed with him was not just the author’s sense of biting critique, still stingingly fresh decades after it was first published, but Baldwin’s relentless hope in America.

This was the same country that had enslaved his grandfather, killed his friends, straight-washed the Civil Rights movement, and poured billions of dollars into surveilling and locking up Black people instead of investing in them. And yet, Baldwin believed that it was still a country of great, often untapped possibility. Thompson was particularly struck by the writer’s idea of bearing witness, and the power that such an act could have. Years after first finding it, the text became a source of solace during the summer of 2020, as Covid-19 and police brutality created parallel and deadly pandemics for Black people in America.

By then, Thompson was in his first year as a graduate student at the Yale School of Music. He had started working on “My Dungeon Shook,” three preludes inspired by the eponymous essay in Baldwin’s 1963 collection The Fire Next Time.

In the essay, written as a letter to his nephew James, Baldwin addresses the insidious, centuries-long legacy of anti-Black racism in America, pulling no punches as he outlines the abuse, harassment, and othering that his nephew will receive from the white world. As he writes, he flows from his nephew’s entrance into the world to the generations that came before him, to the state- and societally-upheld disenfranchisement of Black Americans long after the end of enslavement.

But there is also incredible hope. Baldwin does not simply decry the shortcomings and stereotypes of the white imagination; he urges young James to defy them with his very existence. In what feels like prayer on the page, he reminds his nephew of the love that covers him, of the faith of former generations that has willed him into the world despite its cruelty. For Thompson, the words resonated as if they could have been written in the churn of 2020, during the state-sanctioned murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery.

“Know whence you came,” Baldwin writes. “If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go. The details and symbols of your life have been deliberately constructed to make you believe what white people say about you. Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity and fear.”

BAMN Books LLC owner Nyzae James at a table for the mobile bookstore. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When Thompson finished “My Dungeon Shook,” he didn’t feel like he was ready to move past Baldwin, he said. He was in luck: professor and violinist Peter Oundjian, who leads the Colorado Music Festival, had heard the work and encouraged Thompson to write another piece that engaged with the author’s text. Thompson connected with Princeton Professor Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., whose intellectual biography of Baldwin hit in the thick of 2020.

As he started writing, Thompson was working with “To Be Baptized,” the second essay from Baldwin’s 1972 collection No Name In The Street, and a text that audiences will hear sentences from on Sunday. As he came back to the text, “I wanted something that could communicate James Baldwin’s incredible love of this country,” he remembered. Glaude suggested his letter to Angela Davis, written in 1970.

By that year, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers had all lost their lives in acts of racial violence and aggression. In New Haven, the Black Panther Trials and May Day 1970 had come and gone. Baldwin, who had spent years writing in exile, still insisted that America and its people could be better. And then Thompson fell across the sentence: We cannot awaken this sleeper, and God knows we have tried. It cracked something open.

“His words ‘we cannot awaken the sleeper’ seemed to be in contrast with his entire output,” Thompson said. As he spoke at Stetson, glasses catching in the soft light, he wound the clock forward from 1970 to 1986, when Baldwin addressed the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. At that gathering, Baldwin reminded those who had gathered of their very human interdependence on each other—and how deeply the future rested on recognizing its weight.

“He was acknowledging that power rests with everyone in this room,” Thompson said, adding that there’s a certain bravery in informing the media that they need to be doing their jobs differently. “I want to communicate that hope, but also like Baldwin, hold society to account.”

In “To Awaken The Sleeper,” Thompson does. Knitting together his own music and snippets of Baldwin’s speech, he shows a listener how the act of bearing witness is both necessary and infinite, because America still has so much work to do. As he worked on the piece, he thought about the January 6 insurrection at the United States Capitol. He revisited Baldwin’s words, which seem too stingingly fresh to have been written decades ago.

He bore witness to the ugliness of 2020 and 2021—and chose to hold on to hope.

Wednesday, he acknowledged the darkness and despair of the moment, including a record number of anti-trans and LGBTQ+ bills and attacks on bodily autonomy now affecting half the country. He wants the composition to hold that tension, he said.

“When I read his words, I feel less alone,” he said. He half-smiled. “You can’t gaslight me after I’ve read Baldwin.”

Humanity & Humility

Judge Clifton Graves. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Over the two-hour discussion, Baldwin’s timelessness became a through line, weaving from Thompson’s remarks back to Graves, and then into a question-and-answer session that could have kept the library open all night. Before Thompson spoke, Graves noted that the author also played a seismic role in his life, after he came across the essays in The Fire Next Time as a young man in 1953.

Raised in the Jim Crow South—where he heard Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speak at just nine years old, and later met Maya Angelou—Graves found that Baldwin’s words were a kind of searchlight in the heavy, often thick and oppressive fog of American history. When Graves was in law school at Georgetown University, he had the chance to meet the writer at the Flagship Restaurant, then bustling in the heart of the city. Baldwin was sitting alone, and invited Graves to sit at his table after Graves said hello.

“His humanity, his humility was something that floored me and impressed me,” Graves said. “You know you’re in the presence of greatness.”

Inner-City News Editor Babz Rawls-Ivy. A painting by the artist Marsh inspired by the work of James Baldwin is hanging behind her. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Graves held onto that as he built his own career—first as a legal aid lawyer in North Carolina, and much later as head of Project Fresh Start and city probate judge in New Haven. He often thought about the discrimination Baldwin faced for not just his Blackness, but also the fact that he was gay. When he drew a parallel to King’s advisor Bayard Rustin, who was all but written out of history, a murmur of “Yes!” bubbled up from the second row, where Hill Central School educator Dee Marshall sat listening.

“He was talking about right now,” Graves said later in the evening, when Inner-City News Editor Babz Rawls-Ivy asked how Baldwin still resonates with both the judge and the composer in the present. “The here and now.”

“I think that lots of us are trying to make sense of this world,” piped up a voice from the back of the room. “There’s such a rich history that so many of us adults and young people need to do.”

Part of that, Thompson said, is honoring Baldwin’s legacy by fighting for the world he envisioned—and passing on his work. He pointed to Baldwin’s 1971 interview with Nikki Giovanni, in which the two disagreed at almost every turn in the conversation, but spoke for almost two hours. “He knows the importance of passing that on,” he said.

There with his wife Mubarakah Ibrahim and daughter Salwa, former New Haven police officer and Beaver Hills Alder Shafiq Abdussabur agreed that he would be taking the words with him as he left the library. After finding Baldwin on his still-seemingly-segregated college campus in 1985, he has returned to the text as a teaching tool. Twelve years ago, he folded some of those lessons into A Black Man’s Guide to Law Enforcement in America.

“I just want to remind us that we got work to do,” he said. “If James Baldwin appeared for us today, how would he grade us?”

The New Haven Symphony Orchestra presents Joel Thompson’s “To Awaken The Sleeper” and Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11, “The Year 1905” on Sunday October 23 at 3 p.m. at the John Lyman Center for the Performing Arts, 501 Crescent Street in New Haven. Tickets and more information here. Thompson will appear on the 22nd in conversation with Nyzae James during Elm City LIT Fest.