Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Schools | New Haven Symphony Orchestra | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

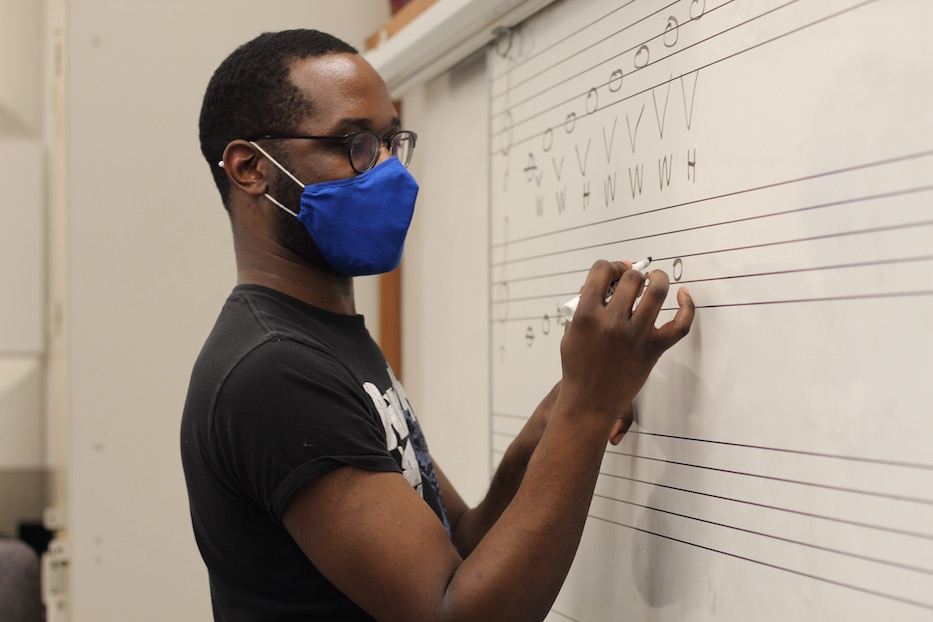

Joel Thompson. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In an Audubon Street classroom, student Liam Melvin watched as his composition flashed up on the screen. The left hand came in slow, steady on the keyboard. Then the right sauntered in, surprising its listener with a bright burst of sound. It glided upward, gathering speed. Violin rose over it, its voice a singsong mimic. As the score ended abruptly, the room burst into applause.

“One thing I like about your work is that you’re patient with your work,” composer Joel Thompson said, his arms extended in front of him to do some of the talking. “As a composer, one of the things you want to be able to say is: ‘Wait for it.’"

Thompson is an award-winning composer, musician, and choral educator based in New Haven, where he is a doctoral student at the Yale School of Music and the composer-in-residence at the New Haven Symphony Orchestra. He may be best known for his sweeping 2014 “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed,” a choral work memorializing unarmed Black men and boys killed at the hands of police officers.

Melvin is a junior at Guilford High School who started a recent class dissing Chopin, and ended it slack-jawed at Stravinsky. What brings them together is the NHSO’s Young Composers Project, which Thompson is supervising during his residency.

Each month, Thompson meets with students in a classroom at the Educational Center for the Arts at 55 Audubon St., workshopping compositions that NHSO musicians will perform and record at the end of the year. While the white-walled, perennially overheated basement classroom is humbler than some of the stages his work has recently graced—the Houston Opera, New York Philharmonic and Kansas City Symphony among them—it is one that he holds very close to his heart.

“It’s the best,” he said in a recent interview with the Arts Paper. “I’m taken back to the first time I fell in love with classical music, and wanting to share the thing that moved me so much. It’s a continual reminder of the joy that I find in that space.”

A Path To Composition

From left to right: Phoenix Geyser, Gabriel Fulton, Michaela Nuñez, Dean Paglino, Thompson, Fareed Samu, and Liam Melvin. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Thompson, whose work is as inventive, moving and sometimes visceral as it is sonically tight, never intended to go into composition. But the field found him—multiple times over—and kept pulling him in.

The first time, he was just nine. Born in the Bahamas (his parents are Jamaican, and his trajectory has also included formative stops in Houston and Atlanta) Thompson was a kid when he discovered his parents’ collection of classical music, and flipped on Tchaikovsky’s “Waltz Of The Flowers.” Within seconds, he was dancing through another universe, conducting an imaginary symphony from the top of his parents’ bed. When the music stopped, he felt his cheeks and realized they were wet.

“That this dead white Russian dude could move this young Black Caribbean boy, I just love that about music,” he said.

That delight never left him. Not in Houston, where he moved with his family at 10, and saw in the city’s diversity what he still calls “the possibilities of this country.” Not in Atlanta, where his family settled years later. And not at Emory University, where he spent four years trying to choose between music and medicine as he took classes in each. In particular, he fed his love of Russian music so fervently that his friends called him “Blackmaninoff,” an endearing riff on the name of composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (the name stuck; it is now his Instagram handle).

When Thompson was at Emory, he began reading the work of James Baldwin, whose words on race, racism and anti-Blackness in America have remained foundational texts in his own work. He remembered picking up the author’s 1962 “My Dungeon Shook,” the first essay in The Fire Next Time, and sensing Baldwin’s brutal, sometimes blistering honesty and also his faith that a better country was possible. In the past two years, they have inspired both Thompson’s “My Dungeon Shook: 3 American Preludes“ and his “To Awaken The Sleeper.”

By his senior year, Thompson had completed pre-med classes and also flourished as a pianist, a course of study that included classes with the composer John Anthony Lennon. He was still on the fence between fields, he said. Then the summer after graduating, he went to a music festival that made the decision for him. “Obviously, music won out,” he said, a smile tugging at his voice.

When he got home, he applied to Emory’s graduate program in choral conducting. It led him to a job at Andrew College, a tiny liberal arts school in Cuthbert, Georgia—the same small town that had birthed the revelatory New Haven artist Winfred Rembert decades earlier. During his time at the school, “I had sort of sworn off composition,” he recalled. “The center of my musical identity was that as a choral educator.”

Anything that he wrote was for himself, in a journal that was, at least for a while, his alone. That was where he first penned his ”Seven Last Words of the Unarmed” in 2014, after police shot and killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and killed Eric Garner in a chokehold on Staten Island. As he wrote “just to get my feelings out,” he folded in the last words of Kenneth Chamberlain, Trayvon Martin, Amadou Diallo, Michael Brown, Oscar Grant, John Crawford, and Eric Garner. They range from “I can’t breathe” to “Mom, I’m going to college.”

Thompson originally put the work away. Then the following year, 25-year-old Freddie Gray died after being held in police custody in Baltimore. Thompson pulled it back out, inviting a group at Emory to sight read it. Someone in the group made a call to Eugene Rogers, director of choral activities at the University of Michigan. It premiered there in the fall of 2015, six months after Gray’s family buried him in Baltimore.

“I didn’t feel like what I was writing was worthy of anyone hearing it,” Thompson said, adding that he didn’t use the label of composer until arriving at Yale in 2018. “I was vulnerable in it in a way that I don’t think that I can be anymore, because I am painfully aware of audiences hearing it.”

It took five years for the piece to take root in the classical music community, a source of frustration Thompson has spoken openly about to the New York Times, and again voiced in a phone interview with the Arts Paper. Then, following the state-sanctioned murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd in 2020, something shifted in the arts. Requests started coming to him. Last year, the Chicago Sinfonietta premiered his “breathe/burn: an elegy,” a co-commission with the NHSO that he described to the Arts Paper as a “memory of Breonna Taylor” in which the very process of grieving, set to music, keeps getting interrupted.

His “To Awaken The Sleeper,” based on and set to three of Baldwin’s writings, premiered at the Colorado Music Festival last summer and went on to Kansas City earlier this year (both of the works are part of the NHSO’s 2022-23 season). In New Haven, he powerfully bridged town and gown with his composition "After," for Nasty Women Connecticut’s 2021 virtual exhibition. The work is based on a letter that Chanel Miller, who for years was known as Emily Doe, read at the end of a rape trial.

It’s a balancing act, he said. He’s intimately familiar with the trend in performing arts institutions to commission and perform works that address the spectacle of Black death and trauma, but go silent on pieces that lift up Black joy and Black genius. He sometimes grapples with feeling “as if I’m profiting off of the death of people that look like me,” he said.

He also sees power in having a seat at the classical table, which for so long has excluded Black people and non-Black people of color, immigrants, and women. He recalled a recent workshop at the Walnut Hill School for the Arts, a private arts high school outside of Boston, where many of the students and their siblings are the same ages that Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Adam Toledo, and Ma’Khia Bryant were when they were killed by police. He watched them grapple with and process the weight of his work in real time.

"Part of a silent revolution, a silent rebellion is not writing for a white audience," Thompson said.

“It’s moments like those where I realize how lucky I am, how grateful I am to be part of music and its inherent power,” he said. “I think my work now is similar to Baldwin’s, in that I’m hoping to bear witness. He emphasized the act of bearing witness. Sometimes it was too painful for him. But there was this sense … [that] as much as this country has hurt me repeatedly over and over and over again, there’s something so special about it that I can’t let go. That’s something I’m choosing to hold onto right now. Hope is the wellspring of my creativity.”

"Part of a silent revolution, a silent rebellion is not writing for a white audience," he later added. "My aim is not necessarily to be original or groundbreaking. I just want to be honest."

That hope makes him doubly excited for his introduction to New Haven audiences on March 18. From the stage at the Lyman Center for the Performing Arts, the symphony will play excerpts of his opera "The Snowy Day," which premiered at the Houston Grand Opera in December 2021. Based on the eponymous children’s book by Ezra Jack Keats, the work brims and then overflows with Black boy joy, enough to spill over from the stage and into the audience.

“I’m so glad that it’s attached to my name so I can crawl out of the trauma pigeonhole box that I've been put in,” he said. “It’s full of whimsy and wonder.”

Lighting The Musical Spark

Fareed Samu, Liam Melvin and Gabriel Fulton.

So too, it turns out, are his monthly lessons with a class of young composers. After spending January on Zoom due to rising Covid-19 cases, all six students were masked and back in the classroom this month, arranged in a half moon of desks around the piano. The six meet in the basement of ECA, in a classroom so unassuming it would be easy to walk right past it. Inside, Thompson builds whole universes between the white boards and a clock where music notes have replaced numbers.

On a recent Tuesday, they shuffled into the room, papers and notebooks rustling as Thompson fiddled with the classroom’s tech setup. A black and white version of Igor Stravinsky’s “Firebird” glowed on the screen behind him. From a stool at the front of the room, he started with a story about his recent trips to New York and Kansas City. His whole body moved, often arms first, as he described his work to the students.

“I hadn’t performed for a while in front of an audience,” he said. “It was thrilling to me.”

All six students have been tasked with writing piano trios that musicians from the NHSO will ultimately perform. In the meantime, they use a variety of programs to work on their compositions, including Finale, Noteflight, Musescore, Garage Band, and Logic Pro X. As Thompson located their work on a computer, they sat at the ready, as if the room might explode in sound at any moment. Every so often, NHSO Education Director Caitlin Daly-Gonzales jumped in with a pointer from the back of the room.

Thompson pulled up Michaela Nuñez’ “Sparks of Fireworks” from the bunch. Nuñez seemed suddenly bashful. She sat up straighter, her eyes wide above her mask. She explained that she was trying to get to A Minor, and wasn’t always sure how to do it.

“I have no idea what time signature it should be in,” she said.

Thompson smiled beneath his mask. “Can we listen to it a few times?” he asked.

Within seconds, the room was filled with the sound of violin rising over a ribbon of piano. Their two voices rose slowly, winding around each other. The piano soared, sometimes leaping forward. If a listener closed their eyes, they could see light spreading its fingers slowly across the sky, unhurried.

“Alright! Beautiful!” Thompson said as students clapped. “I think you’re on a good path here. I want to see what would happen if it were faster. I’d be curious to see what this would feel like double the tempo.” He snapped his finger to a beat to illustrate.

“I think it’d be chaotic!” Nuñez said. “I was thinking … slow motion fireworks.” The line got masked smiles and a few giggles across the room. Beside her, ECA junior Phoenix Geyser seemed delighted by the idea.

“Keep experimenting, keep exploring,” Thompson said. He cautioned Nuñez’ to “look out for these giant leaps” that a pianist would need to make in real life, when a person was playing her compositions instead of a computer.

The program is meant to give each student that level of attention—and Thompson does. With Nuñez, he debated the merits of a Lydian sonority while also praising her ability to disobey bar lines. At Gabriel Fulton’s galloping, almost courtly piano and winding viola, he celebrated arpeggiation before helping Fulton figure out where the piece was going. When Melvin surprised the class with a sprinkling of notes that became a whole call-and-response, Thompson led with his delight.

“Oh, that’s delicious!” he said as he played a few measures back on the piano, sight reading the score over his shoulder. Even behind a mask, Melvin beamed.

Members of the class listened closely to each piece, and to each other’s work. As Guilford High School junior Fareed Samu centered contrasts in his “Piano Trio II”—instruments that almost sounded angry at each other—Thompson sank into it, listening multiple times.

“A lot of my other pieces have been loud and fanfare-y,” Samu said as Thompson pulled the piece up on screen. He wanted to do something different. As piano and violin split from each other, nearly at barbs, it seemed he had succeeded.

“You are thinking methodically about all of the instruments. You are thinking horizontally about all of the instruments,” Thompson said, pausing. He wondered aloud what the piece might need, and realized it was space.

“These are just four bars,” he said. “I want you to start thinking on a bigger scale. You don’t have to put all of your ideas in four bars, or in eight bars. It’s okay to have your ideas take the time it takes.”

Phoenix Geyser, a junior at the Educational Center for the Arts.

A few weeks into the semester, Thompson’s guidance has also given students room to experiment. Geyser, for instance, said she can’t stop listening to Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2, and is folding it into her work. Last Tuesday, she brought in a piece that opened bombastically and built toward climax before slipping into a waltz.

The fake out was so surprising that Thompson and students exchanged sudden looks, as if someone had dropped a secret about classical music in the middle of class.

“I love listening to music and writing music that invites the listener to listen to it,” Thompson said. “I’m excited to see what happens next. Thanks for teaching me how to compose.”

"Just Listen!"

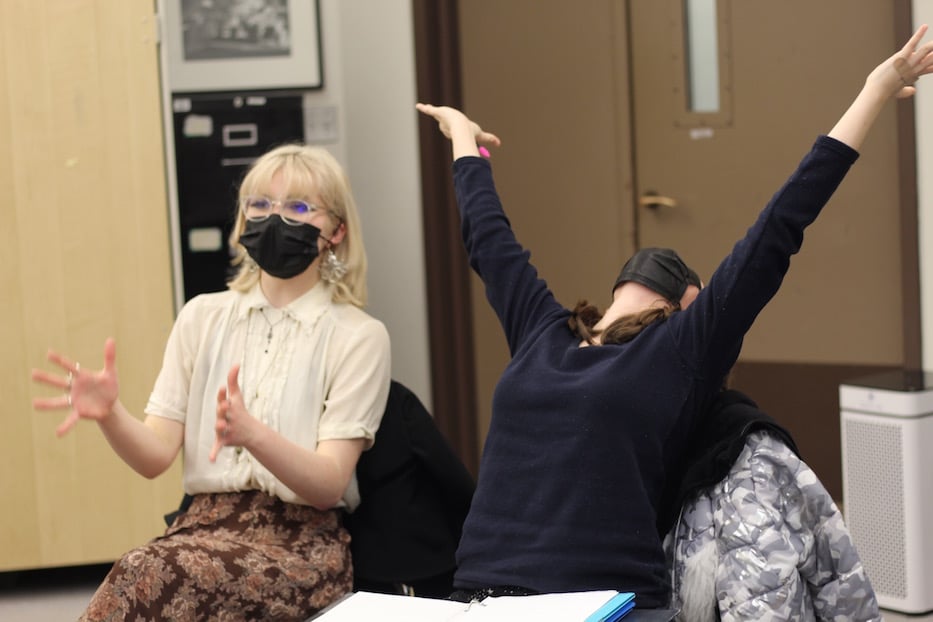

By the end of the class, students embraced their right to move triumphantly to Stravinsky—even from their chairs.

With half an hour to go, Thompson pulled Stravinsky’s ”Firebird” back up on screen, pointing to violins' harmonic glisses and dramatic, often hairpin-sharp musical turns that have so firmly secured the piece in the annals of music history. Part of the class is close listening, from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Bogoroditse Devo” (“Listen to the emotional trajectory of this thing!” he said last Tuesday, shaping the music with his hands. “The best five-one in music history!”) to the “Firebird,” which the NHSO will play Feb. 18 at the Shubert.

He eased into it as notes swirled around each other, humming and swaying from his perch as bassoons bellowed a sort of invitation and strings responded. In the class, Nuñez and Geyser realized that they could move to the music. Their shoulders loosened up as they began to flick and raise their wrists in time with a rising sonic tide.

“This is just like a warm hug,” Thompson said as the beginning melted into sweeping strings. He buzzed between the seat and the projector, noting chord progressions that turned the piece on its head, then righted the ship to make it “feel like home.” Moments later, he was pointing out a dialogue between the horn and clarinet.

“What are they saying?” Dean Paglino asked.

“Just listen!” Thompson responded.

Nuñez picked up on something deep in the music. “They’re flirting!” she said.

“Oh I love that,” Geyser chimed in beside her.

Next to her friend, she too had started to dance in place, still rooted firmly in her seat. She was almost beside herself when oboe came in with what Thompson described as “the sound of the forest” on all sides of the listener. By the final two minutes of the song, her hands had traveled from her lap to in front of her sternum, as if they were clasped in supplication.

They unclasped, palms facing the screen as her fingers spread out. Nuñez lifted her whole carriage triumphantly towards the ceiling, arms soaring above her head. In teaching the Stravinsky line by line, Thompson had started a conversation for which the two needed no words at all.

It echoed something he’d said on the phone two weeks before the class, just days before leaving town for a premiere of “The Places We Leave” at the New York Philharmonic. He called that work, a collaboration with the poet Tracey K. Smith and countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo, a meditation on love and loss. In teaching, he said, he wanted to instill in students the same close looking that Smith did for herself in the piece, and that he works to do as a composer when he sits down to write.

“I’m hoping to use the power of music that I respect to facilitate conversations, in getting us talking to each other,” he said. “I feel like music is a space that can help us to coalesce, and to hold each other’s stories.”

Listen to Babz Rawls-Ivy's interview with Thompson on WNHH above. The New Haven Symphony performs Stravinsky's "Firebird" on Feb. 18 at the Shubert Theatre. It will perform excerpts of Thompson's "The Snowy Day" on March 18 at the Lyman Center for the Performing Arts at Southern Connecticut State University. For tickets and more information, click here.