Arts & Culture | Newhallville | Visual Arts | Community Heroes | COVID-19

Lucy Gellman Photos.

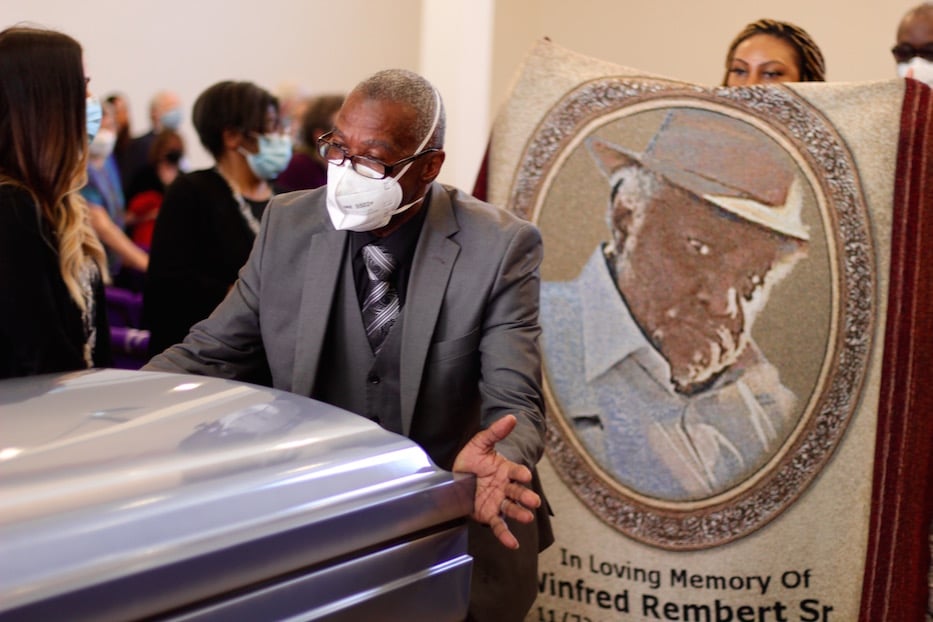

A montage of leather-tooled cotton fields and home videos turned First Calvary Baptist Church’s back wall into a cacophony of color. Beneath them, a tapestry of the artist Winfred Rembert hung on an easel, lips pursed. His carving tools sat nearby, glinting among wreaths of fresh flowers and a blue-grey casket.

Over 100 mourners gathered Wednesday to remember and celebrate Rembert, an artist of towering talent who lived in the city’s Newhallville neighborhood until his death at the age of 75. The artist, whose well-deserved acclaim caught up with him late in life, died on March 31 in his Newhall Street home. His wife, Patsy, was with him at the time of his death.

After a service at First Calvary Baptist Church, Rembert was buried in Grove Street Cemetery Wednesday afternoon.

“I’m not ashamed to say that Winfred was the smartest one in the family,” said Rembert’s younger brother, Wayne Johnson. “He had a God-given talent to exceed expectations in whatever he set out to do.”

Those who filled the church’s pews on Wednesday included friends, family, neighbors, and fellow artists, some in tears even as they entered the sanctuary. All who spoke over the course of the three-hour memorial painted a picture of Rembert as a big-hearted protector, who advocated for his children and always made sure there was enough room at his table for anyone who needed a meal. All remembered him for his gift for storytelling, including in his intricate tooled leather carvings.

“Today as I stand here, I never thought that Winfred would be gone and I would be here,” said his sister Lorraine Reaves, speaking beneath a glittering mask and tall hat fitted with black ribbon. “I believe that he made it into heaven. And a lot of people don’t know that Winfred could sing. But he could sing. And right now, I believe that he is up there singing with the heavenly choir.”

He is now buried at Grove Street Cemetery, in the company of artists, abolitionists, war heroes, and inventors. Wednesday, the New Haven Board of Alders honored his life with a formal proclamation, presented to the family by Newhallville Alder and friend Delphine Clyburn.

"It was a blessing for me to know the family," she said Wednesday. "I'm am so grateful."

During his lifetime, Rembert wore dozens of hats, from justice fighter to doting father to nationally and internationally recognized and self-taught artist. He bridged worlds with his work, bringing together diverse, often kaleidoscopic American audiences to witness his lived experience of the Jim Crow South and enduring love for the woman he found in its midst. Those included a near-lynching, self-discovery in the Baptist Church, and years of backbreaking labor as a sharecropper and later on a chain gang.

Delphine Clyburn, who presented a proclamation on behalf of the city.

Wednesday, the sheer reach of his impact was visible as nuclear and extended family, curators, art historians, documentary filmmakers, and lifelong friends filled the sanctuary in socially distanced rows. Muffled sobs mingled with vibrating keys from the church band, and drums that seemed to start right on time.

Opening with scripture, friend and collector Micky Pratt recalled how quickly Rembert’s notion of “family” went beyond both blood and race, in a phenomenon that is still rare for a segregated city and country. A few years ago, she visited him in the hospital under the pretense that she was his daughter. When a nurse protested—Pratt is a middle-aged white woman—Rembert yelled from his room that she was, indeed, family. He insisted that hospital staff let her through. Pratt walked past the scowling nurse to check in on her friend.

That sense—that Rembert always had the capacity for one more person in his life—was a lifetime in the making. Born in Americus, Georgia in 1945, Rembert was raised by his aunt Lillian and several of his siblings, a list that now includes eight sisters and three brothers who are still living between New York and Georgia. As a child, he never learned to read or write, sent into the state’s sharecropping fields when he was young. No matter, said his grandson Winfred Rembert III: all of his family members knew that “papa was a genius.” It just took the wider world, including the art world, a little longer to get that message.

Rembert toiled for most of his youth in Georgia’s sprawling cotton fields, which today appear in much of his artwork. At a one-man show at the New Haven Museum in 2015, he recalled his mother and aunt Lillian carrying him around in a sack as they picked cotton. Decades later during his time in New Haven, he rendered those scenes vividly, in leather compositions where white puffs and tall, swaying stalks stretch out to meet a flat, glinting horizon line.

When he wasn’t in the fields, said Johnson, he was playing with other kids in the area. Johnson recalled arriving at a pickup basketball game one afternoon, and getting picked on name recognition alone after other players realized he was Rembert’s brother. When the other boys saw that Johnson didn’t have the same knack for the sport, they still humored him. Attendees laughed and clapped as he told the story, bringing his older brother’s spirit into the sanctuary.

Johnson marvelled at his brother's ability to remain open-hearted despite the hand that he was dealt. After attending a civil rights demonstration in 1965, Rembert was thrown in prison without charges and left to stay there. After a year in the jail, he escaped by clogging the prison’s toilets. But he was caught, stuffed in the trunk of a car, and taken out to a field in Cuthbert, Georgia, where he survived a near-lynching. He was forced back into prison, where he had to work on a chain gang until 1974.

Those years were pivotal for two reasons, friends and family said Wednesday. While Rembert was in prison, he learned to tool and carve leather, although he did not begin turning it into artwork until moving to New Haven in the late 1980s. The chain gang is a recurring motif in his work, its black and white stripes undulating in dozens of his compositions.

Those years were also when Rembert—always a smooth talker, said Johnson—first saw 16-year-old Patsy Gammage, who would become Patsy Rembert. According to Johnson, Patsy was the love of Rembert’s life from the moment he laid eyes on her. Rembert begged her to talk to him—including piling dirt in front of her school bus—until she finally relented. It was one of the early indications of a man who did not allow his spirit to be broken, whatever the roadblocks in his way.

Rembert's wife Patsy. "I'm ready to be part of his world," she said Wednesday.

The two knew each other “as well as two people could,” she said Wednesday. Wiping away tears that fell over a white medical mask, she spoke briefly about his piece All Me, a cacophony of color in which Rembert depicted himself as multiple people, in an effort to show the multiple identities he held, often not by choice, in a single lifetime.

The two had a rhythm, she said. She raised their children, and he made a living that was somehow always enough to support their family. She said she looks forward to the day when the two of them can be reunited, him wrapping her in his great, warm arms.

“I don’t have to tell you about our love story,” she said. “It speaks for itself. He was always by my side. I was always by his side. He wasn’t perfect, but he was perfect for me. I will forever be his wife.”

Wednesday, his eight surviving children painted a picture of a man whose energy seemed infinite, echoed in his great, full-bellied laugh and huge, luminous smile. To them, Rembert was a protector, a prankster, and an innovator with tools and the know-how to use them. When they were young, he was the dad who built a basketball hoop from plywood, discarded rusted metal, and mesh netting in the driveway. As they got older, he was famous for feigning surprise when family cookouts nearly outgrew the yard.

One after the other, all of them mentioned his love for their mother, to whom he was devoted from the first moment he saw her in the 1970s. His eldest son, Winfred Rembert, Jr., recalled a family that always had enough love for one more seat at its kitchen table, no matter how crowded the kitchen got.

“I don’t think my dad knew how famous he was,” sad his son, Patrick Rembert. “We have to be great for mom. That was his goal, to have us take care of her. And I know that it feels like we’re saying goodbye to him, but we’ll all carry a piece of him.”

Lillian Rembert: "All I know is, my father held me high."

Lillian Rembert, who is named after her father’s aunt and is the family’s eldest daughter, remembered seeing her father burst through the door one day after work as a longshoreman in Bridgeport. At the time, the family was living in Bridgeport’s Father Panik Village, a housing project that they later left for New Haven. She was young, with aspirations of one day riding a bike like her older brothers.

Her mother had just put pork chops on the stove. Rembert held up a new pink bicycle—"I mean pink pink, with white wheels and a basket,” she said to a wave of laughter—and informed Lillian that she was going to learn to ride before the day was over. When she hesitated, her father reminded her that she was named after a woman who could do anything.

After several attempts that left her running into cars around a parking lot, Lillian was ready to give up. Rembert gripped the back of the seat and pushed the bike forward. As she remembers it, he lifted her clear off the bike and into the air with one decisive swoop. The bike ran into a telephone pole. Rembert didn’t care.

“All I know is, my father held me high,” she said. “We are his legacy, and we are his best, most loved creations.”

Almost everyone who spoke praised him for his artwork, which included vivid, often traumatic scenes of his childhood and adolescence rendered on dyed, carved, and tooled leather. Rembert did not begin making work until he was in his 50s and living in New Haven, after years of encouragement from Patsy. In the last quarter century of his life, he became a world renowned artist.

Phil McBlain.

In 2000, his work became the subject of a one-man show at the Yale University Art Gallery, creating a relationship with then-Director Jock Reynolds that lasted through Rembert’s death last week. In a 2015 show at the New Haven Museum, his works covered the walls of several galleries, springing to life as they depicted rows and rows of cotton, performances at juke joints, home cooking, worship services in church, and scenes and scenes of white violence on Black bodies.

They became his primary storytelling device and an invitation to bear witness to the lasting scars of anti-Black violence, white supremacy, segregation, and the carceral state. In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative honored him for his work, later writing that “we celebrate his life of truth-telling about American history through his brilliant and compelling art.”

Friends remembered him for his sharp wit and surprising humility, matched only by a gift for storytelling. Phil McBlain, an antiquarian bookseller based in Hamden, met Rembert over 25 years ago, after he and Patsy had moved to New Haven with their family. He recalled the gratitude he felt each time Rembert reached into the annals of his memory, and pulled out a new story, from jumping on stage with James Brown to the violence he experienced as a Black man in 1960s Georgia.

“He was a natural storyteller, and he loved talking about himself and his life,” he said, close to tears as he remembered the hours of conversation. “He would say, ‘Can I say I’m an artist?,’ and I would say yes, and yes again.”

In 1996, Rembert gave McBlain a leather carving for Christmas. McBlain later sold it, he said, and gave the profit to Rembert. It marked the early years of the artist’s now-legendary career. His voice wavered as he recalled the last time the two spoke. Rembert had called last Tuesday night, during a basketball game that McBlain wanted to catch. McBlain asked him to call back in the morning. When his phone rang the next day, it was Rembert’s namesake, Winfred Jr., explaining that his father hadn’t made it through the night.

Vivian Ducat.

Rembert wasn’t phased by the fact that his work was in rarefied collections, added documentary filmmaker Vivian Ducat. Exactly 11 years ago this month, Ducat met Rembert in New York City, at a gallery opening of his work where he was the only Black person in the room. She approached him and asked where he had learned to tool leather, immediately interested in learning more when the answer was a straightforward “prison.”

Those stories made her fall in love with Rembert. She ultimately directed All Me: The Life and Times of Winfred Rembert—and became a member of his and Patsy's extended family in the process. Wednesday, she remembered a man of huge stories and small kindnesses, who threw open the windows of a studio to let all of Harlem know that they were filming, and later quietly taught her young son Hugo to tool leather on his front porch.

"Winfred had such a big, deep world, and I am proud to be a part of it," she said. "I loved him, and my family loved him, and I will miss him."

In August of this year, over 80 of Rembert's works will appear in Chasing Me To My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South. Erin Kelly, a Tufts University philosopher who worked with Rembert on the book, said she is devastated that he will not be able to see the publication come to fruition. Speaking briefly towards the end of the service, both she and literary agent Stephanie Steiker vowed that they would work to keep Rembert’s life and legacy alive through his artwork.

“This is what this gift is,” said Steiker. “His story, in his own words … it’s up to all of us to lift him up and share his story.”

Tywanna Johnson, John Rembert, and Tracey Massey after the service. All were wearing masks before taking the photo.

Already, those works have left an indelible mark on some of Rembert’s New Haven viewers. Sitting in the back rows Wednesday, artist Tracey Massey said that she cannot see Rembert’s work without also seeing her own family. Massey’s 80-year-old mother was born and raised in South Carolina, where she still lives today. Like her family, the pieces remind her how recent the history of de facto segregation still is.

Pulled out of school in the fifth grade, her mother never learned to read. Instead, she spent her days working with her sisters on a sharecropping farm. She later married a Korean war veteran and began raising a family of ten kids, in which Massey is one of five girls and five boys. When Massey discovered Rembert’s work a few years ago, it was like looking in a mirror.

“His story took me back,” she said. “Can you imagine the life that they lived, and the strength that they had for their children? That family bond is everything.”

The family and the McBlains have set up a Venmo to help with the expenses of the funeral. The account for donations for the Remberts is listed on Venmo as @sharon-mcblain. If you prefer to send a check you could make it out to Sharon McBlain. Write "Winfred Rembert memorial" in the memo field and mail it to Sharon McBlain, 13 Forest Court North, Hamden, CT 06518.