Dance | Music | Arts & Culture | Nasty Women New Haven | Visual Arts | COVID-19

Imagine. The word pierces the air and stretches across time and space, bending backwards over itself. Voices build on top of each other until they are a cathedral of sound. Imagine. The layers are crystal and silk. Dear one. A listener finds themselves imagining too: a past that could not envision the present, and a future where trans women do not have to justify their existence.

Alexis P. Lamb’s composition For Marsha (P. Johnson) is part of Silent Fire, a virtual exhibition from Nasty Women Connecticut, the Yale Institute of Sacred Music (ISM), and six pairs of composers and multimedia artists running through August 15 of this year. The title comes from Barbara Strozzi’s 1654 Ardo in Tacito Foco (I Burn in Silent Fire), the oldest piece of music in the show. In many ways, it is both the most scalable and the most sweeping show that Nasty Women has put on since it began in March 2017. This marks the group's fifth annual show, and first online.

“We were all navigating a difficult situation,” said Luciana McClure, one of the original co-founders of Nasty Women and one of the lead collaborators on the show. “But we knew that we wanted this project to be something that would really allow for people to have this intimate experience of being in a show … these visual artists [are] responding to these classical pieces, which are narratives of women’s stories as well.”

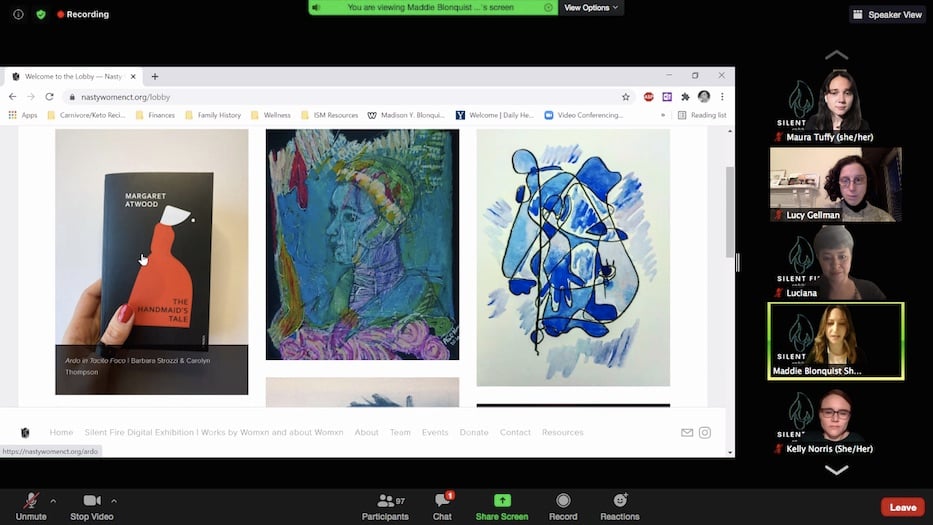

Works pictured above in the "lobby" include Ardo in Tacito Foco from composer Barbara Strozzi and artist Carolyn Thompson; Try Me, Good King from composer Libby Larsen and artist Pearl Lee-ora Kruss; and After from composer Joel Thompson and artist Katie Butler. Butler's practice is based in Connecticut.

The project was born over a year and a half ago, well before Covid-19 was a household name. At the time, Yale ISM students Maura Tuffy and Kelly Norris were already thinking about a collaborative project that paired close looking and close listening, modeled loosely on the “Playing Images” series at the Yale University Art Gallery. When Tuffy saw a flyer for Nasty Women hanging up downtown, she reached out to McClure to find out more. The two met in person a few times. Then the pandemic hit.

As they imagined the project, the team grew to encompass students Maddie Blonquist Shrum and Andréa Walker, as well as longtime Nasty Women team member Louisa DeLand. They have spent the past year imagining and reimagining a show that bridges the distance and embraces a new-old kind of artmaking. A full year after Covid-19 shut down Nasty Women’s fourth annual show, Silent Fire yokes the century-spanning work of six composers with contemporary performance, video montage, visual art, and dance. With video design from Camilla Tassi and sound editing from Liam Bellman-Sharpe, they include source texts by Barbara Strozzi, Libby Larsen, Joel Thompson, Fanny Hensel, Florence Price, and Alexis Lamb.

The six collaborations are the core of the show. Each pairs a composer with musicians who can perform their work, and artwork submitted specifically for the both the "Silent Fire" theme and the piece specifically. In that collapsing of worlds—past and present, silence and sound, victim-blaming and compassion, fury and tentative joy—comes an outpouring of work that is as effective as it is affecting. To it, the project team has added visual and aural aides, close listening exercises, and prompts with which to further explore the music.

The result feels new even after 12 months of slogging through concerts, discussions, script readings, awards shows, and small-scale performances online. In a virtual “lobby,” viewers are greeted with six different project rooms that they are able to enter, each of which marks a collaboration. Each is wildly different: they span the first five wives of King Henry VIII to animations thickly painted on glass. Collaborators have also included a participating artists’ gallery with additional submitted works.

“As you proceed, feel free to move throughout the exhibition sequentially or sporadically, using the ‘lobby’ as your home base,” organizers write in an online text for the show. “We hope that you will spend time with the artists, composers, and performers showcased on each page, further engaging in close looking, compassionate listening, and contemplative reflection.”

The works themselves burn very brightly. In Thompson’s 2018 After, the composer has split the piece into two movements, pulling apart the thick, ugly layers of how rape and sexual assault are currently prosecuted (or more often, not prosecuted) and how they might be of the world led with believing women. The piece is inspired by a powerful letter that Chanel Miller, who for years was known as Emily Doe, read at the end of a rape trial during which she was demeaned, questioned, second-guessed, and grilled on her weight, appearance, sexual behavior, and chronology of the night she was raped.

In the first movement, Thompson opens with a litany of questions Miller faced during the trial, a grilling that may be a familiar gut-punch to many of the work's listeners. During the trial, Miller was asked how she was dressed, how much she drank, whether she remembered horrific details of that evening, and to consider the career of her rapist. In the second, the composer moves into Miller’s trust in fellow survivors. It is anchored by the words “I am with you” and “I believe you.”

Under Tassi’s careful video design, the piece becomes a meditation on both the violence of not believing women, and the anecdote to that violence. A shrieking and rattled violin opens the piece, as much a warning as it is a wound. On screen, mezzo soprano Rhianna Cockrell and violinist Beatrice Hsieh appear, their faces and bodies nearly translucent as the scene shifts, and shifts again. Cockrell releases something from her throat: the questions swoop in.

“How old are you? How much do you weigh?” she sings in a clipped voice. “What did you eat that day? What did you eat that day?”

Still from Joel Thompson's After, with words by Chanel Miller and work by Katie Butler. The work is performed by Rhianna Cockrell and Beatrice Hsieh and compiled by Camilla Tassi and Liam Bellman-Sharpe.

Even through a screen, the questions are scorching and invasive, crashing in on a listener’s sense of privacy. Slowly, Katie Butler’s painting Bodies appears behind the musicians: a torso and legs, gripped by two hands with black nail polish. As violin and voice call and respond—at one point, Hseih appears physically pained as she plays—Butler’s work becomes a third voice. Her second piece, titled After, appears in vivid detail after Cockrell has moved into the second movement, and sings the words “You are powerful” to the rafters.

The marriage of the forms challenges viewer-listeners to use their senses in concert with each other. No sooner does one hear how Cockrell repeats the word “dinner” in three mounting questions than one realizes how curt the violin has become. As Hseih speeds up just after the two minute mark, viewers seize on a sense of panic and second guessing that mirrors Cockrell’s pointed and minute questions. In the accompanying online gallery, curators have broken the piece into sections for deep, focused analysis and reflection.

Tassi’s video editing is a triumph: Cockrell’s face is magnified and front-facing, as if she is both the defendant’s lawyers and the survivor placed on the stand. At times, Butler’s painting bleeds into her face, showing how deeply these storytellers—and stories—are intertwined. When her painting After appears in the final minutes of the work, it lingers like a beacon in a long, dark night.

That glowing spark among creative team members is equally vibrant in Ardo in Tacito Foco. In the exhibition, Strozzi’s piece is performed by vocalist Andréa Walker and theorboist Grant Herreid and paired with Carolyn Thompson’s Silenced. As Walker sings, she becomes a sort of Baroque translator, transporting the listener back to seventeenth-century Italy while never quite leaving 2021. From somewhere within a fiery red dress and matching lipstick, her voice rises, dips, and slows, imparting all the quiet suffering of the piece.

Beneath her image, Thompson’s hands appear over the pages of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, writing the word “silence” in black pen until almost the entire book has been redacted. In her process, Thompson wrote the word some 65,000 times over 14 days, leaving only the sentences that mentioned silence. In doing so, the artist effectively rendered silent the repressive, anti-woman universe of Gilead outlined in the book.

The project feels powerful and horribly prophetic: this week, Thompson watched as mourners gathered to hold vigil for Sarah Everard after she disappeared walking home in London at the beginning of the month, only to later be found dead. Just one night after the exhibition opened online, a domestic terrorist walked into multiple massage parlors and murdered eight women, six of whom were Asian-American.

“The intention for it is to act as a reminder to us all that, although it is often difficult to speak out, we must ensure we continue to fight to make our voices heard, both individually and collectively,” Thompson wrote in an accompanying artist’s statement.

The show’s arc is ultimately a hopeful one, if also bittersweet. It envisions a future that is more unrestricted and joyful than the present, with a full knowledge of the strong women and non-binary folks with whom artists walk (several of the composers are still living). Listeners hear it dawning, cautiously, in Florence Price’s An April Day, where the pairing of soprano Deborah Stephens, pianist Carolyn Craig and artist Carter Norris becomes a visual sound bath. As Stephens looses a songbird from her throat, Norris' work fills the screen behind her, paying homage to both women in photography and the value of art that is frequently dismissed as "folk" or "craft."

Likewise in Lamb’s 2021 For Marsha (P. Johnson), with text from Aiden T. Feltkamp and accompanying choreography from dancer Madison Vomastek. The language comes from Feltkamp's poem cycle “Trans Love and Life,” a contemporary take on Adelbert von Chamisso 1830 poem cycle Frauen-Liebe und Leben. In the work, they forge a place for themselves where there was none, pushing gently on dominant narrative while also using its written traditions. Set to Lamb's score, the piece becomes arresting, probing the meeting of Johnson's life and the literal sublime.

In a video at the bottom of the gallery’s page, Vomastek is in an empty studio, eyes fixed on the camera. Extending her arms to their full wingspan and then curling in, she moves through it all: the often-whitewashed history of the Stonewall Riots, the weight of Marsha P. Johnson’s power and majesty, the mind-numbing number of trans people still killed each year, the majority of them Black and Latinx trans women. As voices rise, she is propulsive, always moving forward. So too does the show.

Original work in the show comes from Carolyn Thompson, Carter Norris, Jacqueline Andrew, Katie Butler, and Pearl Lee-ora Kruss and Madison Vomastek. Silent Fire runs from March 15 through August 15, 2022 online. To enter the exhibition, click here.