Music | Arts & Culture | Music Haven | Yale University Art Gallery

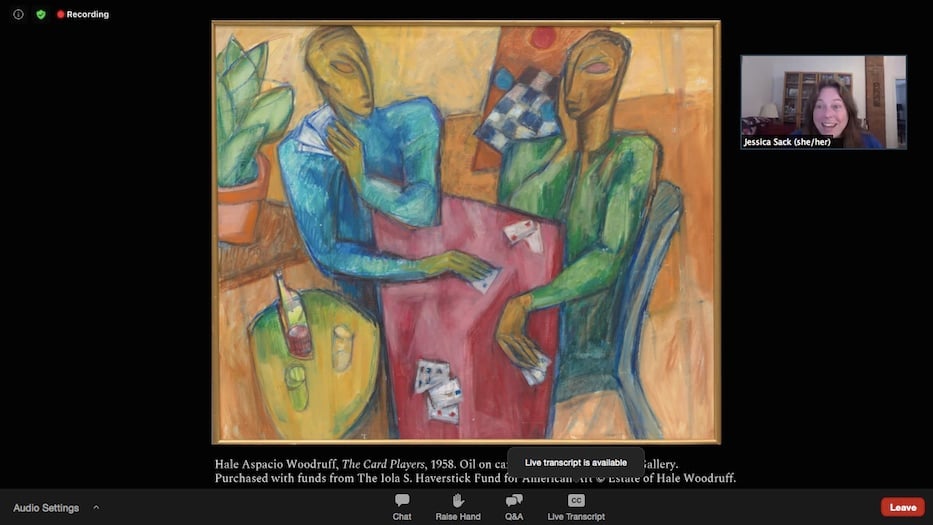

The conversation flowed between the card players, threads of violin and cello so thick they almost trailed smoke. Viola rose, and one player pressed a palm to his cheek, cards hidden on the table in the other hand. Cello became throaty, and the other pulled his arm back, on the defensive as he made his play. Viewers noticed the drained glasses, a half empty wine bottle hanging between them like an invitation.

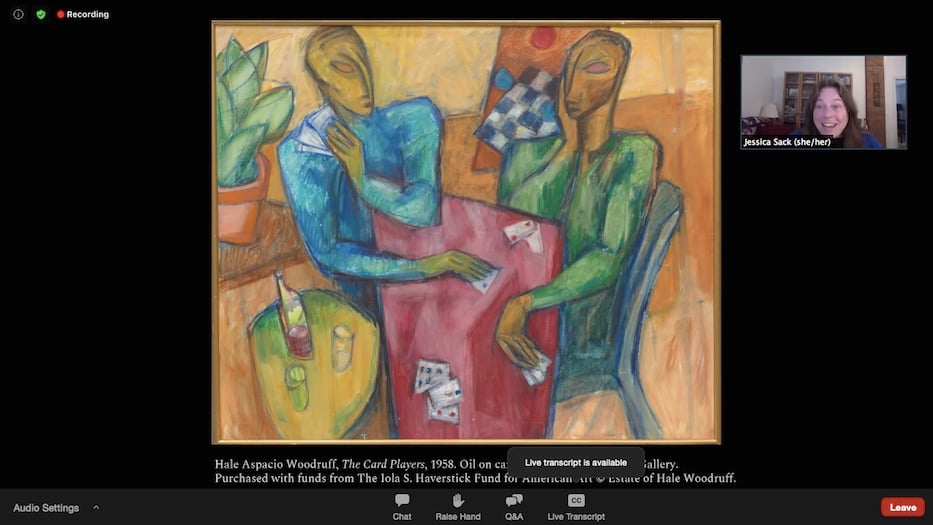

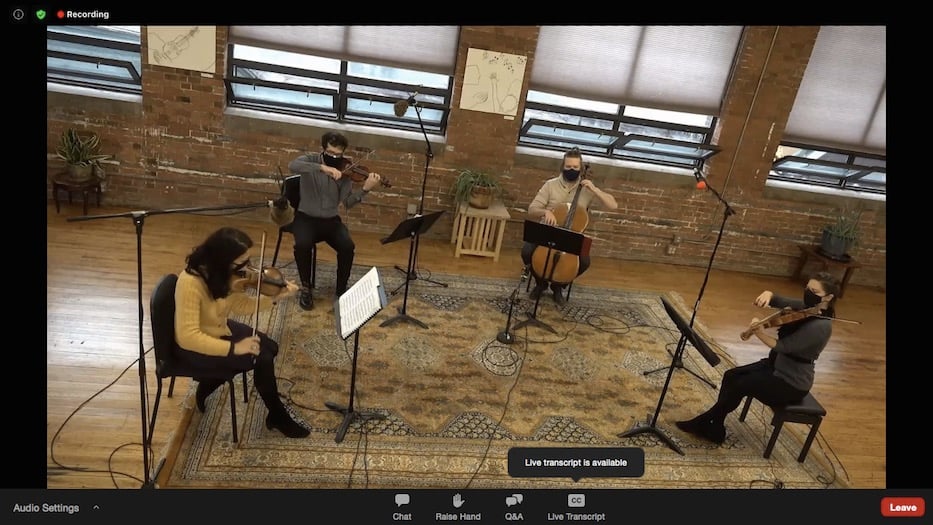

Last week marked the return of “Playing Images,” a collaboration between the Yale University Art Gallery and the Haven String Quartet that has been on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Normally, members of the quartet play alongside an image in the gallery, which has been closed for almost a full year. This week, they relaunched the series online with a close look at Hale Woodruff’s 1958 The Card Players, set to the first movement of William Grant Still’s 1960 Lyric Quartette: Musical Portraits of Three Friends. The Haven String Quartet performed the entire piece last fall, during its first virtual concert of the pandemic.

“What we like to do is think about what the quartet is working on, what pieces in the gallery could fit, and what sonically and visually connects,” said Jessica Sack, the Jan and Frederick Mayer Senior Associate Curator of Public Education, in a phone call before the performance. “With these works, we’re thinking about the ideas of layering—of sound, of history, of art.”

As she and the quartet moved the program online, Sack found herself thinking about friendship and isolation, both of which hum and whisper through both works and through the present moment. The gallery acquired Woodruff’s painting last year, meaning that visitors have not yet had the chance to see it in person. As she prepared for the event, Sack talked to the conservators working on the piece, who described in detail Woodruff’s process of layering and painting over a sketch. He also painted the same theme much earlier, in a 1930 canvas that is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the time Woodruff painted The Card Players, he was a great admirer of Pablo Picasso, Amadeo Modigliani, Constantin Brancusi, and Paul Cézanne, influenced by four years of study in Paris. In particular, it was his affinity for Cézanne that drew him to the card playing motif multiple times during his career. In those years, he also began to study and collect African art, influenced first by a book from Indiana-based gallery owner Herman Lieber, and later during his studies in France.

In a 1968 interview with the Smithsonian, he recalled first seeing African masks while frequenting French flea markets with the writer Alain Locke, who may be best remembered as the father of the Harlem Renaissance. During those years, he also saw how Picasso and his contemporaries had looked to those forms through the European guise of Primitivism, which is Euro-speak for riffing on the foundations of visual culture and civilization itself.

Perhaps for that reason, Woodruff’s The Card Players is most like his predecessor’s in name only. Cézanne painted a love song to male homosociality and populism, where a viewer is locked out of the image by the players’ raised arms. There’s a familiarity there, but also a stiffness, as if the players are huge versions of the artist’s apples, rearranged and unmoving. In reality, many of the men he painted were farm laborers who he paid to model for him. He was able to picture them so readily—to have access to their aching, tanned, work-toned bodies—because of his own proximity to funds and generational wealth.

Woodruff’s canvas, meanwhile, is wonderfully untethered and cacophonous; a viewer can feel the movement flowing through it. There’s a controlled riot of color, enough to keep pulling a viewer back time after time. One figure pulls their hand away and smirks, playful or perhaps defensive. On the right, the other has eased into the game, their wrist snapped back in a manner that doesn’t seem possible. Both players are angled out out at the viewer, leaving the composition open. Both have one arm on the table, their fingers mere inches apart. The artist doesn't feel like a distanced chronicler so much a friend who has showed up with a paintbrush in hand at just the right time.

The piece is bright and warm, in a departure from his earlier canvas of the same theme. Here, Woodruff has flattened out the canvas, almost as if he is hovering overhead as he paints. The sharp angles—of the red card table, of a plant in the background, even of the players’ mask-like faces—make rounded, muscled and sketch-like strokes that much more pronounced. Beside the two players, a half-empty bottle of red wine suggests the two might be at this game for a while yet.

And why not return to the motif later in his life? Woodruff was, in many ways, more free in Paris than he was in his birth country. During his time studying there, he was friends with several of the Black artists, writers, thinkers, and musicians who were mountains of the Harlem Renaissance, including the painter Palmer Hayden and the sculptor Augusta Savage. When he returned from Paris, he helped spearhead work among Black artists and students in Atlanta that he later called the “Atlanta School." He taught at an HBCU, and is still recognized today for his 1938 mural cycle of the Amistad rebellion that he completed at Talladega College in Alabama.

He wasn’t just aware of the need to nurture other Black artists: he acted on it. Maybe The Card Players isn’t the best illustration of that legacy: his murals, archival covers of The Crisis, and work on Ebony magazine’s 1963 “Emancipation” issue all speak to that work more loudly. But in its own quiet way, the painting captures that too: he used it to fold in American folk art, Cubism, and the influence of African art, of which he was a collector from the 1920s to his death in 1980.

No sooner had the program begun Wednesday than it was hard to see one piece without hearing the other. Still’s first movement is dedicated to “The Sentimental One,” with an undulating melody that a listener feels like they can crawl right into. The opening is slow but not sorrowful, steeped in a language of folk reclamation, blues, and Black spirituals. As it unspools, it’s easy to imagine a conversation between two friends, their faces dear and familiar to each other. When played over the painting, it felt like a piece fitting into a puzzle.

As the music seeped out onto screens across New Haven, gallery staff focused on details of the painting, sweeping over the image so viewers could get a closer look. Beside the work, members of the Haven String Quartet appeared in masks, their eyes wide and talkative as they played six feet apart from each other. Because the four had prerecorded the piece, they were able to comment in real time, answering questions as they arose in the chat. Just as they once did in the gallery, quartet musicians played the piece all the way through, then returned to sections to allow for close listening.

Yaira Matyakubova. Screenshot from Zoom.

“When we speak about the layering in music, we think about the role of each voice in harmonic structure and how each voice fits together,” said Yaira Matyakubova, artistic director at Music Haven.

In the chat, attendees chimed in one by one, just as they might have if they’d been sitting in the gallery on folding stools. One noted that they felt the warmth of the music, “as though this is an experience among friends.” Another picked up on the intimacy between the two players. A third suggested that if the two were Black like their maker, they were likely playing a game of Spades—just as she had seen her own family members do while growing up.

In that way, both artists chart a quiet sort of resistance: they create a seat for themselves and their listeners at a table heaped with the ghosts of dead white men. By knitting their work into Western, largely Eurocentric conventions, they are able to pay homage to, challenge, and subvert them all at once. In Still’s use of the pentatonic scale, a listener finds themselves second-guessing everything they have been taught about the value and weight of “folk” art. A contemporary listener might hear strains of Jessie Montgomery’s Banner, a work that sometimes feels as explosive and exuberant today as Lyric Quartette may have in 1958.

So too in the painting. Before his death in 1980, Woodruff championed Black history and Black culture in at least three countries—the U.S., France, and Mexico—and across the American South. He lived and worked in Atlanta at a very specific time, when his contemporaries included sociologists and intellectuals Ira de Augustine Reid and W.E.B. Du Bois. He was close with the Black composer William Dawson, whose sweeping Negro Folk Symphony is often relegated to college choirs and symphonies. The Card Players, like Lyric Quartette, is a reminder of the tens of thousands of Hale Woodruffs who weren’t remembered not because they were lacking in talent, but because of the color of their skin.

Steeped in history, the gallery’s new painting is a document of a specific time in American art. But it also speaks directly to a question Black, Indigenous, and People of Color artists are still asking today: who gets to make art? What kind, and how are they recognized for it? More broadly, who gets to shape collective historic and artistic memory? It’s a question that is long overdue for the gallery, which has only recently begun to reckon with its own entrenched white supremacy.

“The composer and the painter, they were contemporaries,” said Matyakubova, adding that there is no evidence the two met, although they traveled in many of the same circles. “There were parallels in their lifetime. William Grant Still … he was paving the way for generations to come, and way ahead of his time."

To find out more about events at the Yale University Art Gallery, click here. To find out more about the Haven String Quartet, including an upcoming concert on Feb. 13, click here.