Fair Haven | Music | Arts & Culture | Music Haven | COVID-19

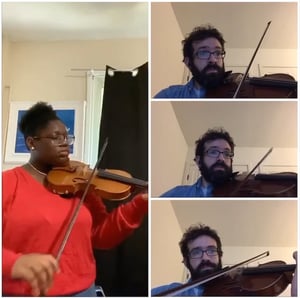

Rachel Ababio Screenshots.

Horse-hair bow struck the string. The sound was resonant, reverberating past the brick room’s walls and breaking clear out its windows. Energy crackled between flying fingers and fingerboards. Players shook with intensity as they crossed strings, their trembling wrists pulsating pitch. Something big was brewing.

On Saturday evening, Music Haven premiered American Hymnal to virtual audiences. The concert marked the first installment of Album Drop, Music Haven’s newest online series. Album Drop is a collaboration with WMNR Fine Arts Radio, which will rebroadcast the concert on Dec. 6 of this year over YouTube.

The series will include four shows during its run, featuring performances from Music Haven’s resident Haven String Quartet as well as student soloists. After each program, audiences will be able to engage with performers in live Q&A sessions. The series joins Music Haven’s efforts to shift online during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Thank you so much to everybody who came out and experimented with us as we try this new format,” Haven String Quartet’s violinist Gregory Tompkins said Saturday. “Thank you to everybody who put questions in [the chat] for us, as well. It’s such a wonderful way to be together.”

The livestream’s chat function filled quickly with virtual cheers and excited questions as American Hymnal launched. Reign Bowman, a seven-year veteran of Music Haven, prepared to play Antonín Dvořák’s “Humoresque” for violin. Tompkins, her teacher, accompanied her on his own violin.

Bowman began with short bows as Tompkins plucked a harmony beside her. The theme glided by, and the chat sang its approval. Bowman was focused, moving her left hand up the violin’s fingerboard as her right hand laid strong, steady bow strokes.

She was shifting. String players use the technique to play a wider variety of notes on the same string. Bowman shifted from first position—a violinist’s neutral hand placement—to third position for the first time.

“I think what makes it difficult is having to keep your posture still the same and moving your hand down,” she said. “You can’t let your thumb stay too far back—that’s what I had trouble with.”

Tompkins said he could not have been prouder. He noted her “incredible progress,” which has happened despite the pandemic. Her performance was the culmination of countless hours spent on Zoom with him, and additional hours practicing scales and runs over and over. Despite COVID-19, Bowman has scheduled lessons with Music Haven staff at least four times a week virtually. She was (and remains) committed to learn, she said. Music Haven was committed to teach.

The next performance opened with a combination of “pizzicato”—string plucking—and “arco,” or bowing. The Haven String Quartet sat in a socially-distanced semi-circle, its sound filling up its spaces. They moved together, bodies swaying to an invisible beat.

It was a conversation. Lead violinist Yaira Matyakubova set the tone—casual. She gave mid-length bows with medium pressure, no vibrato to be found. Violist Annalisa Boerner gave a sassy response—her strings snapped against wooden fingerboard as she plucked hard and loud. Matyakubova pressed more weight into her bow. She gave a syrupy glissando for extra measure. Tompkins agreed with her point, joining her melody with bowed harmony.

Cellist Phillip Boulanger oscillated between the two groups, sometimes growling out an arco statement or thudding out a pizzicato reply. Boerner plucked in indignation—this time, she added percussive raps on her viola to accentuate her points. Conversation had turned to heated debate. Boerner explained that the piece was titled “The Purchaser’s Option” by Rhiannon Giddens.

“The song was inspired after reading an advertisement in a book for a human being, for a young woman—she’s 22, young, a good worker—that kind of thing,” Boerner read, quoting Giddens on her creation of the piece. “And at the end of it, as if an afterthought, it says she has with her a 9-month-old baby who is ‘at the purchaser’s option’ … this song came out of that. Thinking about what her life was like and how lucky I am. The chorus of the song goes, ‘you take my body, you can take my bones, you can take my blood, but not my soul.’”

Boerner finished the piece with a viola solo, mournful and dark. Matyakubova accompanied with a soft, resolute, left-hand pizz. They looked at each other. All four then looked to each other, eyes burning above their masks.

“I could actually feel your eyes on me, Annalisa,” Matyakubova commented after the fact. “I feel like it’s almost like we have a third eye opening.”

The final piece was a three-movement work—“Lyric Quartette” by William Grant Still. Still was a prolific musician, composer, and arranger. He had many firsts to his name—first African American to premier an opera with the New York City Opera, to premier a symphony with a major orchestra, to conduct one.

He taught himself violin, viola, cello, bass saxophone, and clarinet. He’d bop in big bands, swing in jazz clubs, and perform in orchestral halls. His music was eclectic yet masterfully precise.

“Lyric Quartette” was no exception. Its three movements represented Still’s relationships with three friends. They stood together in disparate cohesion.

In the first (“The Sentimental One”) The Haven String Quartet played with bows languid and smooth. Each note was warmth. Vibrato saturated each phrase. Harmonies were lush and full. Dynamics were exaggerated, as if the musicians were wearing rose-colored glasses. Members of the group moved in time, sometimes slow with longing or fast in fits of passion. The movement called for embellishment and ornament: It danced through trills and grace notes and shivered in tremolos and laid flat in the sun of open strings. Sometimes, it whispered a harmonic, silently drifting high above.

It fused into a second movement (“The Quiet One”) that was soft-spoken, yet had a large presence in the room. The movement began in unison, quiet and haunting. It had a duality, a complexity hidden in slow passages. Melody and countermelody bounced from player to player. This was subdued yet intense; players made no visible cues but seemed to know by heart when they should play. Each line was a whisper, coming together in a poignant plea. It built to “The Jovial One,” the third and final movement of the work.

The movement was fast and klezmer-like. It ran from arco to pizzicato, tacking on every ornament it could find along the way. The musicians played call-and-response across instruments, lines echoing back and forth. Some tried spiccato—bows bouncing against strings—bounding and leaping past sense and consequence. Heavy down-bows meant arms flying away from musicians’ bodies. Light up-bow and arms squeezed to chests. The piece repeated itself. It stuttered into genres and then backed away as if burned.

Speaking on the piece, Boulanger mentioned the number of references he hears each time he plays, including the Czech composers Dvořák and Janáček, as well as Tchaikovsky. He joked that he hoped the audience had enjoyed listening as much as the group had enjoyed playing. Saturday marked their first concert together in eight months.

“I think with COVID times, I’m re-thinking about everything,” Matyakubova said. “It just made me realize that every time we meet is such a precious time, and it means so much more to me now. I think about when we were pre-COVID—when we were meeting, we were just talking about ‘this’ and ‘that’ and all these things that were there in front of us to figure out. Then, the fact that we were together playing just felt like ‘Of course, it’s there.’ Now that we were separated for a while, and now that you have a chance to actually meet in this beautiful space and play together, it’s very, very special.”