Culture & Community | Music | Arts & Culture | Music Haven | COVID-19

| Zoom. |

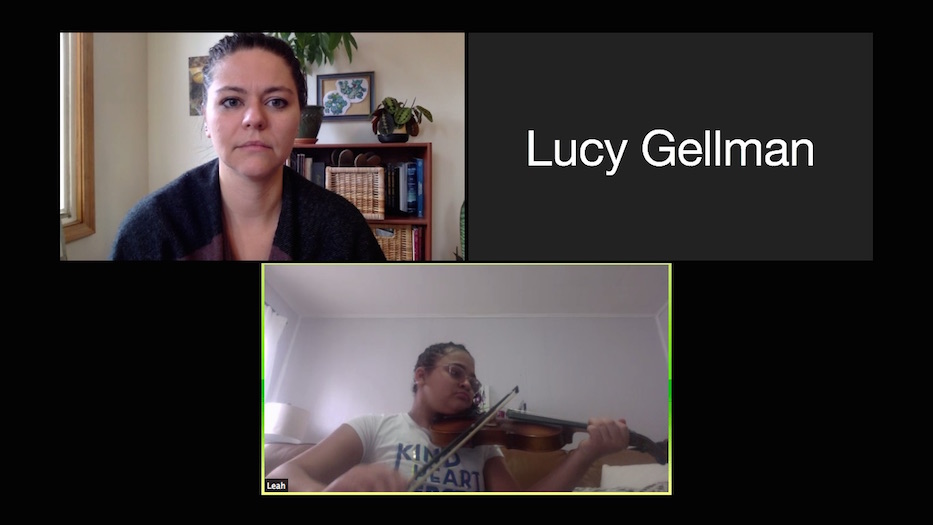

Leah Carrillo rested a pint-sized viola beneath her chin and started in on her G major scale. In a pixelated box to her upper left, Annalisa Boerner watched every movement, eyes fixed on the screen. Leah played out the notes, turning her shoulders just slightly. The bow slid across the strings, a controlled, squeaky explosion of sound. Boerner nodded and then broke into a cautious smile.

“If I’m right, this means you’ve finished your scales,” she said. “When we are back together again, that means I owe you either ice cream or pizza!”

Boerner is one of five teaching artists at Music Haven, a local nonprofit that normally offers tuition-free music lessons, homework help, and mentorship to roughly 80 New Haven students out of its Erector Square offices. Ninety-one percent of the organization’s students identify as non-white; 82 percent come from families below the Federal Poverty Level.

So when New Haven’s schools closed last month due to COVID-19, the nonprofit went into triage mode, trying to ensure that students had laptops, internet connections, and access to food. A few final spring student recitals were taken off the calendar. Haven String Quartet concerts were cancelled for March, and then for the rest of the year. The organization closed its doors March 13, the same day that schools shut down across the city.

“All of our musicians are still working on getting in touch with all of our families, making sure basic needs are met, and figuring out what the technology situation is at home in order to make a lesson plan for each family,” wrote Executive Director Mandi Jackson in an email in mid March.

Less than a week later, teachers were churning out individual lesson plans with a mix of Zoom, FaceTime, Google Duo and YouTube. Milda McClain, who serves as director of operations and outreach, wrote on the website that she will be starting online groups for parents and guardians to also connect, share support, and interact.

Each teacher has taken a slightly different tack: violinists Yaira Matyakubova, Patrick Douane and Gregogy Tomkins have been teaching largely over Zoom and FaceTime. Boerner, who plays viola, and cellist Philip Boulanger have been mixing those methods with weekly practice videos over YouTube.

Boerner said she’s been “pleasantly surprised” by how well the system works, given the limitations of not being in the same room—or the same building, or even the same neighborhood.

Speaking from a home studio turned Zoom room, she described her process, which has included meeting with students one-on-one, and then recording practice videos with assignments and advice for the pieces they are working on.

In a given week, she might record up to 16 videos, and hear back from most of her students. She has been in touch with all of the families. In a recent lesson, she and Leah plowed through G Major scales (“Expert hooks! Very nice!”) and then onto J.S. Bach’s Minuet Three.

At one point, Boerner listened through the end of the piece, then asked about section C, which the two have been working on through the practice videos.

“Why did your brain do ‘tee tee’ notes?” she asked.

There was a beat. Through the screen, Leah cocked her head to the right. Her long mop of brown hair, gathered in a ponytail, moved with her. She had done the same thing last week, she suggested. That was part of it, Boerner said.

“Brains love patterns,” she explained.

“But Bach didn’t!” Leah responded. The retort, crisp and snappy, flowed right back into another go at the song.

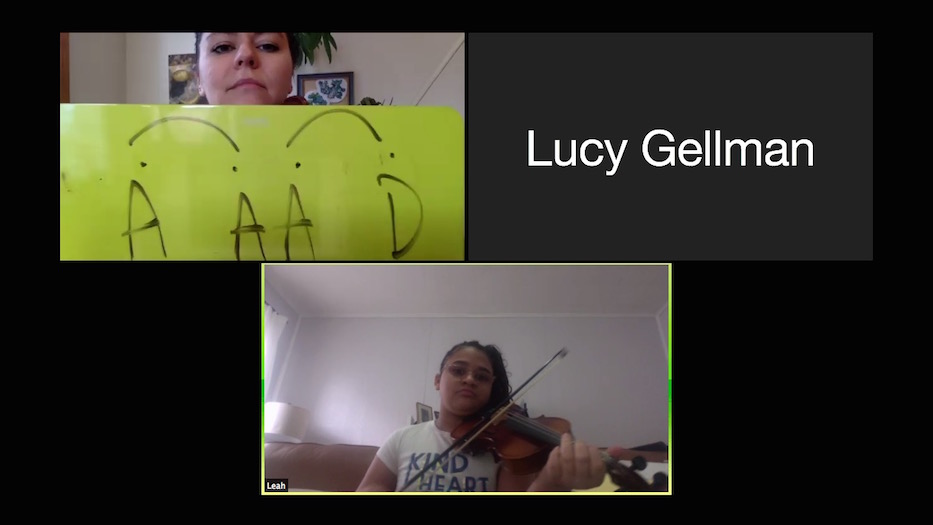

In the practice videos, students are primed for this sort of close listening and learning. Boerner puts up snippets on the screen, so that students can study them in black and white. She talks them through them with rhythmic “tees” and “taas” as she plays. For most of her students, that method has been working: Leah is almost through her current book. She’s finished everything except Robert Schumann’s “Happy Farmer,” which comes next.

“I’m giving information out in smaller bites,” Boerner said after the lesson. “And I’m trying to teach the practice slowly, efficiently.”

There are also challenges that aren’t so easy to fix over a screen, she added. If a student’s instrument is out of tune, she has to find the right words to use to describe a quarter or half twist in either direction, because she can’t reach through the internet and fix it. If a bow breaks, she can no longer run to the back offices, where extras are kept, and do a quick trade.

She recalled a contact-free bow drop off a few weeks ago, and an instrument repair where she let the case sit in the corner of her room for three days before touching it.

“I feel like I am settling in,” she said. “I like having the structure of seeing them. But I also … I really miss them. I miss the community. I miss the joyful noise. I try not to think about it too much because there is so much uncertainty.”

For now, it’s what she and her students have to work with. She celebrates when there’s a strong internet connection and has learned to be patient when it’s glitchy. She tries to not let long freezes bother her. With the help of fellow musicians, she’s discovered that there are tools to a smoother-sounding lesson, including asking a student to back up when they play, and then approach the computer as they listen.

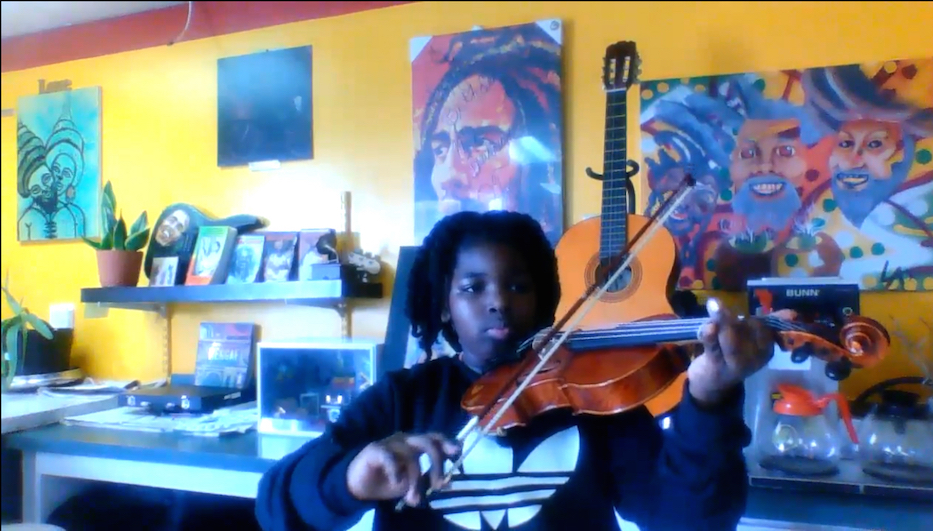

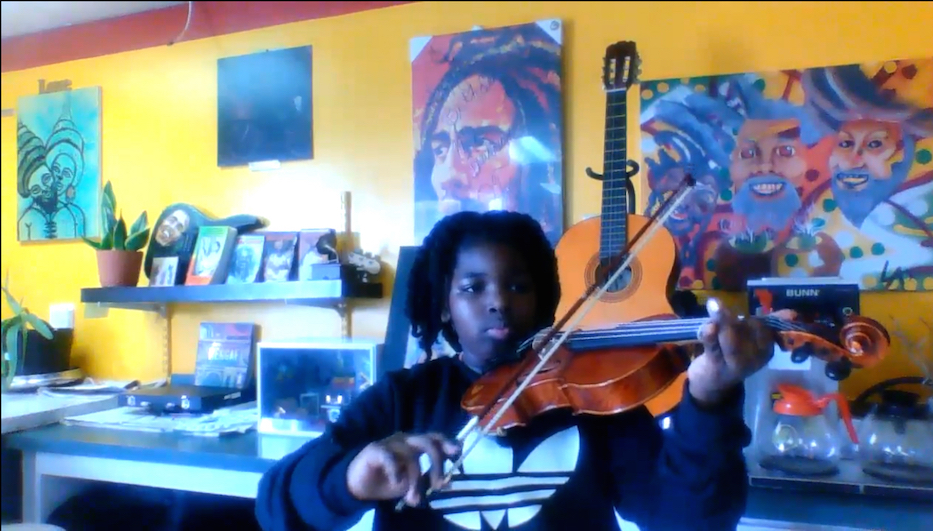

| Marlee playing in front of her namesake. Elisha Hazel Photo. |

Elisha Hazel, a Music Haven parent who runs Ninth Square Caribbean with her husband Quelen Wright, praised Boerner for making sure that her students “have everything they need.” Her daughter Marlee, a student at Amistad Academy, has been playing for two years with Music Haven.

With school closed, she often takes her lessons from the restaurant, where she works on a laptop that her grandparents gave her last year for Christmas. Hazel has encouraged her to play when she’s bored, which has recently included trying to figure out covers.

"They've been great," she said of Music Haven. "I feel like Marlee is actually getting more lessons."

Before COVID, Hazel said she thought the computer wasn’t necessary. Now she can’t imagine what Marlee would do without it. As her daughter navigates online learning, she and Wright navigate a world of curbside pickup, apps like GrubHub, and unclear information from the state about when things might reopen.

“We're doing all right,” she said. “We're trying to keep going, to offer help to those that need it. There's nothing that nobody can do right now, so we're kind of all in the same situation.”

Other teachers have also experimented with that teaching format. Boulanger, who created a YouTube channel where his 16 students can upload their work for feedback, has been doing near daily check-ins with his students, and watching videos come back in response.

So far, he has sent out and received over 300 videos, including weekly encouragements with lush snippets of his own cello playing.

He’s heard back from 13 of the 16 kids each week. While he worries about “certain things that don’t translate to online lessons,” he added that he can envision a post-pandemic world in which he continues doing practice videos alongside in-person lessons.

“It’s been a really sort of interesting transition,” he said in a recent phone call. “For some kids, it seems to have really clicked. We’re asking: how can we have a way to check in and monitor practicing?”

The check-in videos have also given students an outlet to talk to their teachers about the pandemic, without ever mentioning it by name. In a recent cello lesson, Music Haven student Justin Jenkins told Boulanger how much he misses his classmates.

“All of our students seem to hunger for normalcy,” he said. “Part of these check-ins is just having part of the routine from which they’re completely untethered. It’s like, 30 percent musical improvement and 70 percent giving families something to look forward to every day.”

In a recent response video to Boulanger, Justin sets up his small cello in the middle of a wide stance, his face fixed on a camera that sits on the table in front of him. He admits, eyes locked with the little camera lens, that he’s not sure what scale to begin in, or if his cello is correctly tuned.

But, he continues, “just like my teacher Mr. Philip said, just try. So I’m going to try.”