Culture & Community | Public art | Public Health | COVID-19

Cyclists Max Chaoulideer and Ben Midyette. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A white “ghost bike” sits at the corner of York Street and South Frontage Road, chained to a pole. On one side, medical students and nurses pass in their color-coded scrubs, sometimes pausing to take a look. On the other, cars zoom past, speeding up before they get on the highway. In bone white from its handles to its wheels, it keeps watch over the intersection.

It hasn’t been abandoned. It’s there to memorialize Keon Ho Lim, a 25-year-old Yale law student who was struck and killed while biking at the intersection in October.

Sunday afternoon, members of the Safe Streets Coalition of New Haven gathered to remember the 11 cyclists and pedestrians who have been struck and killed by vehicles this year in the city of New Haven. The memorial was part of the internationally recognized World Day of Remembrance for Road Traffic Victims, which the United Nations adopted in 2005. It was held at the intersection of Elm and Temple Streets, where 53-year-old pedestrian Milton Williams was struck and killed in July.

Safe Streets Coalition of New Haven members Lorena Mitchell and Kai Addae.

“We’re here today to honor the lives of those lost in traffic crashes,” said Kai Addae, co-director of the Bradley Street Bicycle Co-Op and a member of the Safe Streets Coalition. “Any death is one too many, and this year in New Haven, we’ve lost more to date than all of last year.”

In the last five years, 200 cyclists and pedestrians have been killed and hit in vehicular collisions in New Haven. This year, fatalities include Arthur Bastek, Kevin Anthony Cunningham, Maurice Messier, Gilberto Molina, Govinda B. Kandel, Anthony Little, Julio Ruiz, Williams, Eric Joseph Pechalonis, Celeste “CeCe” Staten and Lim.

While the deaths span the city’s 18.7 square miles, they tell a damning story of city and state negligence, including in neighborhoods with higher Black, Latinx, immigrant and resettled refugee populations. Last month, Lim was struck at the same intersection where 42-year old Melinda Trancredi was killed in 2017, and Yale medical student Mila Rainof was killed in 2008. After Lim's death, a push from the university to make the intersection safer drew both praise and criticism from safe streets advocates, who have called for the same amount of attention at intersections and thoroughfares across the city.

This year, three fatalities took place within a quarter mile of each other on Ella T. Grasso Boulevard, including one at an intersection that has proved deadly and prompted multiple calls for city and state action. Pechalonis was struck and killed on August 31, at the same intersection of state routes 1 and 10 where 38-year old Shaneka Woods was struck and killed by two cars in September 2017. Bastek and Little were both killed nearby.

In 2017, Connecticut Department of Transportation (DOT) spokesperson Kevin Nursick also outlined the department’s plans to add significant pedestrian safety measures, including new signals, by 2020. Then nothing happened. To cross, pedestrians and cyclists still must brave multiple lanes of traffic as cars turn on both sides of them. On one side of the wide avenue, there’s still an unmarked bus stop, grass sprouting out of the cracked asphalt. On the other, a well-worn footpath snakes through the grass in lieu of a sidewalk.

“Too often, the city and state are prioritizing speed and convenience of cars over equity and safety of all people,” Addae said before reading out the names of those killed this year.

Sunday, cyclists pushed for better urban infrastructure and a renewed commitment to New Haven’s Complete Streets Ordinance, which has come under fire from both elected officials and community members since its passage in 2010. After taking a moment of silence for the victims of traffic violence, a few attendees stepped forward to recount the losses and close calls they too had experienced across the city and over the border into Hamden.

Sabrina Whiteman, who is finishing her graduate degree in public policy and administration. As a former Beaver Hills resident who now lives downtown, she said she often feels unsafe as a pedestrian.

Sabrina Whiteman, who joined the coalition earlier this year, recalled the number of collisions and near-collisions that she witnessed while living on Anita Street in the city’s Beaver Hills neighborhood. Sandwiched between Ella T. Grasso and Ellsworth Avenue, the street is home to several families and young children who play outside. When she heard about the coalition, she joined with those kids in mind.

“I feel like there should be a special coloring to get drivers to slow down,” she said, noting that she has watched drivers blow through white-striped crosswalks across the city.

She added that as a pedestrian, she rarely feels safe. Before moving downtown, she often walked to work from Beaver Hills. Whalley Avenue, where Staten was killed while searching for her dog, quickly became “the bane of my existence.” She watched cars turn right on red at all hours of the day. It felt like she was taking her life in her hands.

“There’s this lack of empathy, or lack of care, following simple signage,” she said. “This is a walking city, but it’s like you walk at your own risk.”

Melinda Tuhus.

Melinda Tuhus, whose advocacy frequently has her cycling between New Haven and her home in Hamden, recalled thinking she was going to die at the intersection of Orange and Trumbull Streets in New Haven’s East Rock neighborhood. On her way home one night, Tuhus was waiting at the light when she watched a car turn into her lane and begin accelerating. She “screamed as loud as I could,” she recalled. The car swerved and narrowly missed her.

She advocated for the 20IsPlenty Campaign, which goNewHavengo and safe streets advocates launched earlier this year in an effort to lower the speed limit to 20 miles per hour. The more slowly a driver is going, Tuhus noted, the less likely they are to injure or kill a pedestrian or cyclist—or collide with them in the first place.

Addae remembered Mark Angeles, an avid biker and classmate of hers at Reed College who was killed nine days after graduating, when a truck took a left onto an intersection where he was riding. Addae recalled his kindness, sense of humor, and brilliance in and out of the classroom. In an instant, a driver cut his life short.

“Too many of us have stories like this,” she said. “Preventable crashes, not accidents, that should be fixed by our city and state. There are things that we can do that can prevent it, and can save lives.”

A ghost bike, installed Sunday, now memorializes David Toles. Ben Midyette Photo.

From the back of a circle, Max Chaoulideer stepped forward to speak. That morning, he and cyclist Ben Midyette had driven to spots between New Haven and Hamden, installing ghost bikes in locations where cyclists have been struck and killed. The tradition dates back to 2003, when St. Louis cyclist Patrick Van Der Tuin witnessed a fatal collision and installed a bright white bike and sign as a memorial. There are now hundreds across the country.

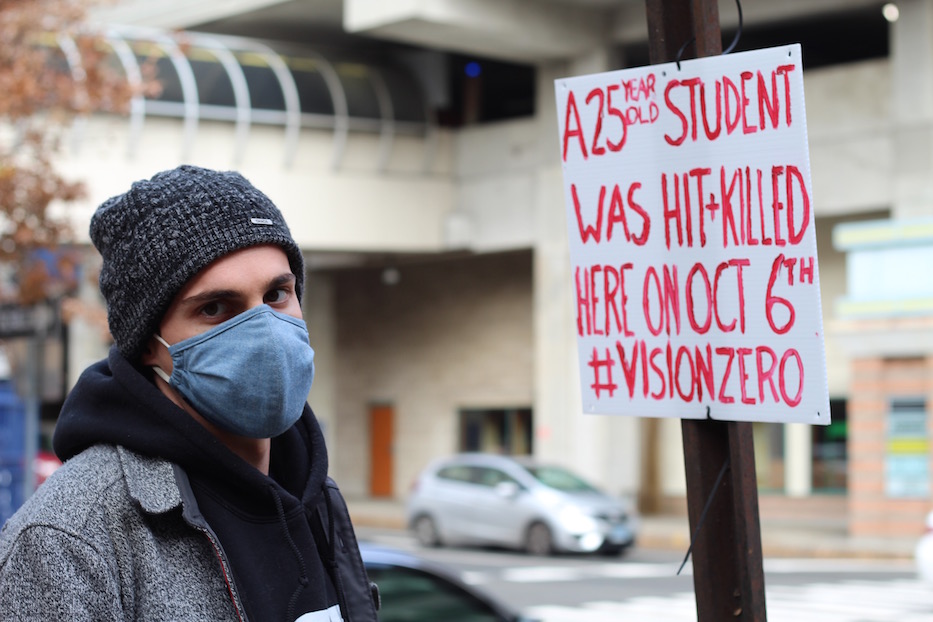

Sunday, the two installed ghost bikes at South Frontage and York Street and Grand Avenue and Ferry Streets, where Lim and Ruiz lost their lives earlier this year. The two also made a stop on Dixwell Avenue, where 54-year-old cyclist David Toles was killed in September. Each stop has a hand-painted sign memorializing the person who was killed, their age, and cause of death.

Saturday, Chaoulideer also installed a bike in Wallingford for his friend and fellow cyclist Donald “Donny” Carrelli, a 37-year-old Milford resident, doting uncle and marine veteran who was struck and killed in Wallingford last May. On a sun-soaked, warm afternoon, Carrelli was on his way to get ice cream after a New Haven Bike Month block party. Chaoulideer was with him at the time of the crash. A Meridan man who had been driving drunk later pled guilty to manslaughter.

“I’m sure other of you have stories like that,” Chaoulideer said Sunday afternoon. “Anyway, if we can just think about people like Donny and others who died or been severely injured and come together and make it so that going to get ice cream, or going to work, or any of the things that should be normal are not scary and dangerous and potentially fatal.”

“It’s absurd, and reflects so poorly on the way that we prioritize and organize our society,” he added. “And it is tied to so many other things that have brought us here also, regarding transportation. It’s not simply a matter of how you move. It’s a matter of how you enjoy life, how you get to work, and how you see your friends.”

After the event, Addae said that the coalition plans to spend the winter pushing for city and state action, starting with a new session of the state legislature that begins in January, as well as meetings with the Connecticut chapter of the ACLU and Greater New Haven NAACP to discuss red light cameras and enforcement strategies that don’t necessarily involve police.

In addition, the coalition has asked the city to roll out a “Vision Zero transportation strategy,” which envisions a city with zero pedestrian and cyclist fatalities per year. The push is part of a larger nationwide Vision Zero movement; read the coalition’s full Vision Zero statement here.