Visual Arts | Sculpture | COVID-19

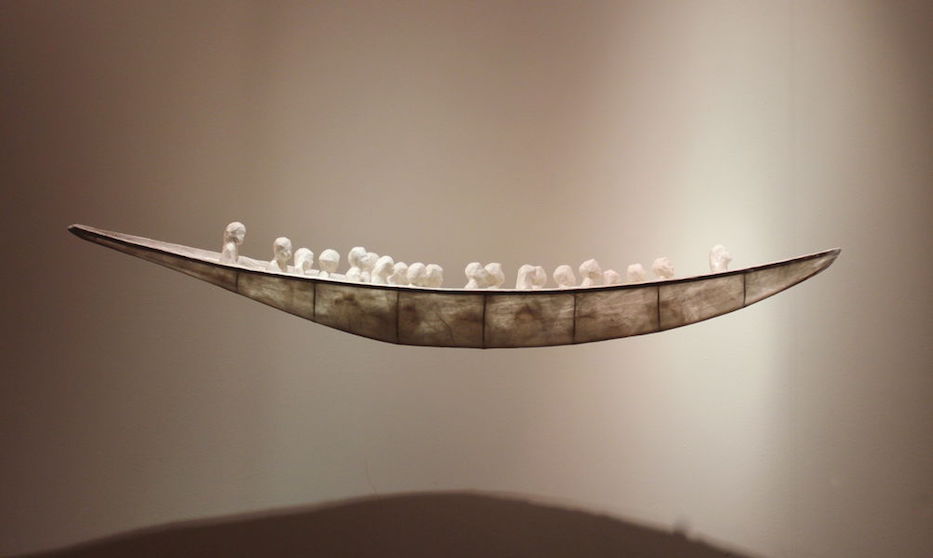

Susan Clinard's Twenty, which the artist sculpted in 2013. "I don't know if we're anywhere near ready to heal,” she said in a phone interview Monday. Photo courtesy of Susan Clinard.

The boat hangs low, swinging almost imperceptibly. Inside, children sit shoulder to shoulder, their faces still soft. Some appear to be looking forward; others tilt their heads to the sky. The bottom of the boat registers their weight: 20 tiny bodies, so bright white they are emitting pure light.

The figures in Twenty represent the 20 first graders killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. eight years ago this week. With six teachers, they were among the youngest victims of domestic terrorism in United States history. Each year, New Haven sculptor Susan Clinard returns to them in her Sandy Hook Memorial, a two-part work that she sculpted in the aftermath of the massacre.

Each year, she thinks about the families who lost children that day—and how many more have lost children, relatives, and friends since. A pendant sculpture, Six, depicts the six teachers in a circle, their backs facing each other as they hold hands. Eight years ago, all of them were killed while protecting their students.

“Every time images surface on this day, I go there again,” Clinard said in an interview Monday afternoon. “It’s like I’m sitting in the same place, just remembering the flood of feeling. I want to remind myself and others of another place that these little people are in. I feel like there needs to be a visual prayer, a visual sense of hope and allowing families a sense of peace.”

It has given her space to grieve and to let others grieve, she said. Eight years ago, Clinard’s oldest son was in third grade. Her youngest was still a baby. She and her husband struggled to explain what had happened to their boys. She recalled sitting in her studio and feeling waves of grief. The sculptures let her work through the trauma and exhaustion she was feeling.

“The process is as true as the way I approach artmaking today,” she said. “This was eight years ago, and I still make work where I am moved and inspired and upset. Sometimes the work just kind of reveals itself to me, and sometimes I just have to sit on it. It's a hard thing to talk about, because sometimes I don't understand it myself. It's hard not to feel things when others are hurting.”

She didn’t know that it would do the same for others. Shortly after the massacre, she sent several of her small, meditative boat sculptures to families who had lost children that day. She keeps “such an insanely beautiful letter” from one of the victim's fathers tacked to the wall of her studio, a constant reminder of both his loss and the small, meaningful way art can help people grieve and heal. Each year, a woman sends her a poinsettia on December 14. She only signs the card sometimes.

This year—which has seen a citywide rise in gun violence amidst the pandemic—has felt particularly heavy for the artist, and for those around her. In her work, Clinard has taken time to address the parallel pandemics of COVID-19 and white supremacy, including in a youth-led project called Emancipation Takes A Knee last month. She said she feels enraged and wounded by the divides in access and wealth that she sees in her own community each day, many of which COVID-19 has laid bare.

“I'm completely and utterly exhausted,” she said. “I'm completely physically drained. It’s just this constant reality of how far you have to go. I'm even more raw. I think like so many of us, we're tired. We're tired. I don't know if we're anywhere near ready to heal.”

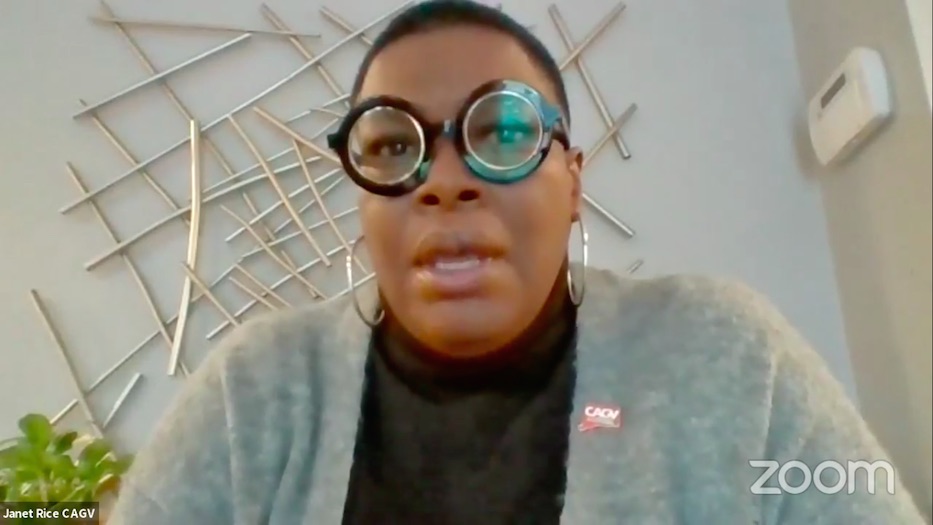

Janet Rice, whose son Shane was killed in Hartford in October 2012, speaks at Monday morning's vigil. Screenshot from Zoom.

Monday, her private reflections joined more public vigils across the state, held online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Monday morning, faith leaders and elected officials gathered on Zoom for a vigil organized by Connecticut Against Gun Violence. Monday evening, Newtown’s Trinity Episcopal Church also held an interfaith vigil online.

“It is unthinkable that it's been eight years,” said U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy Monday morning. “Those little boys and girls would be starting high school this year. Those parents, those women, those educators inside of those classrooms would have had eight fantastic years of personal growth time with friends, maybe marriages, maybe children of their own. It's been eight years, and yet the pain feels so unbelievably fresh.”

He urged viewers to push their elected officials—including himself and fellow U.S. Sen Richard Blumenthal—to pass gun reform legislation that makes acquiring and using guns, particularly semiautomatic weapons, much more difficult than it currently is. Last year, Connecticut saw 181 reported deaths related to gun violence.

As he remembered 20-year-old Shane Rice, Hartford’s 20th victim of gun violence in 2012, Murphy drew a line from the first graders at Sandy Hook to the victims of gun violence who have died in urban areas including Hartford, New Haven, and Bridgeport. Rice’s mother, Janet, is now the outreach coordinator for Connecticut Against Gun Violence.

“What happened in Sandy Hook is not inevitable,” Murphy said. “It is not unchangeable. And that there are laws on the books of the United States today that make that kind of horror, that kind of carnage, much more likely than if we were able to pass a set of different laws that made it harder for anyone to be able to get their hands on a weapon of that power and carry out a crime of that magnitude.”

Janet Rice, a Hartford mother, also painted gun violence as an entirely preventable epidemic. Fighting tears, she spoke about the difficulty of organizing the vigil this year, as she and her colleagues took in the sheer magnitude of loss of the past eight years. She told virtual attendees the story of her son, who was shot and killed during an argument in October 2012. He was on the way to a vigil for his friend Angel, who was declared missing in 2011.

When she heard about Sandy Hook just 55 days after her son’s murder, Rice said her first impulse was to run to the parents and wrap them in her arms. Eight years later, she grieves the fact that so little has changed on the legislative level. She recalled driving past makeshift memorials on the side of the road, where she knows that Black and Brown men in Connecticut have been shot and killed at a rate far higher than their white peers.

“Those 20 little precious souls were not lost, they were prematurely snatched away from their families,” she said. “Just as my Shane was snatched from me. Together, we need to take a stand to stop all we can to stop this vicious cycle. We need to do everything we can to stop, reduce, and end gun violence in the state of Connecticut. And it can be done. It can be done. We can do this.”