Elm Shakespeare Company | Arts & Culture | Theater | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

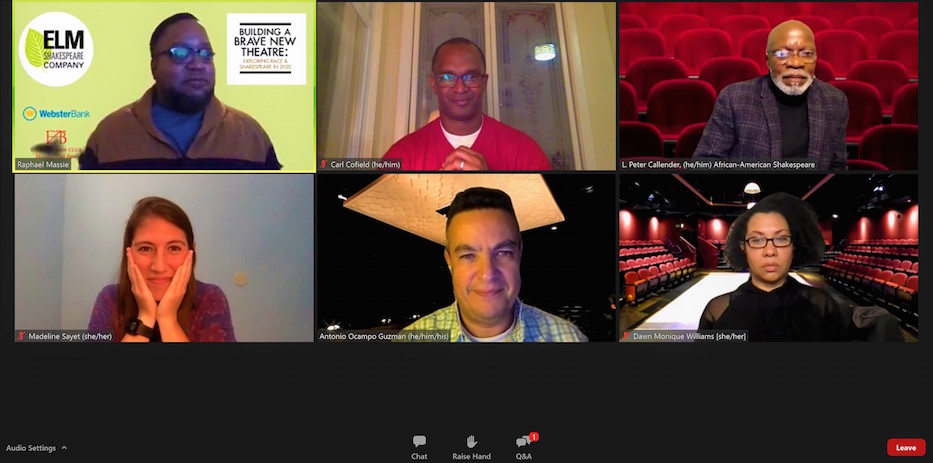

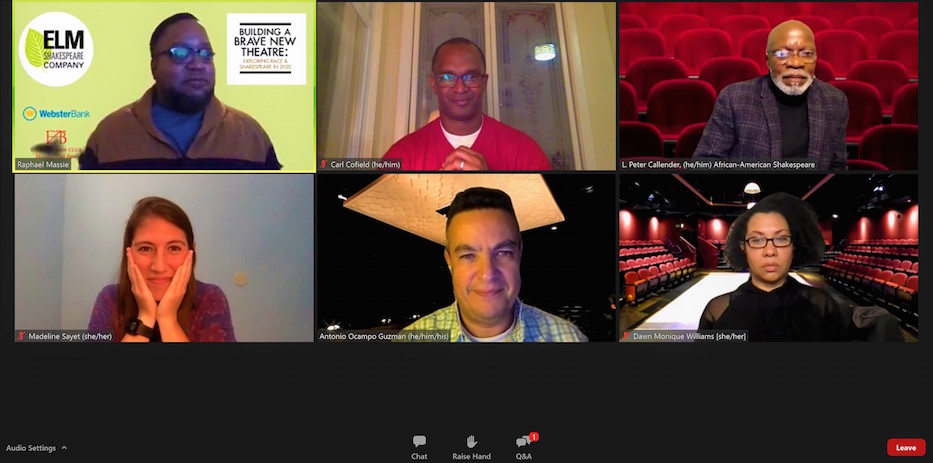

Screenshot from Zoom.

Is Shakespearean canon immutable text? Can practitioners adapt works to fit the contemporary moment? Is the Bard truly meant for everyone?

The questions set a panel ablaze Thursday evening, during Elm Shakespeare Company’s virtual "Shakespeare BIPOC Director’s Forum.” The panel featured directors Carl Cofield, L. Peter Callender, Antonio Ocampo-Guzman, Madeline Sayet, and Dawn Monique Williams. Elm Shakespeare’s Raphael Massie moderated the event.

The panel is the second installment of Elm Shakespeare’s “Building a Brave New Theatre: Exploring Race and Shakespeare in 2020.” The five-part series runs through Dec. 10 with support from Webster Bank and the Elizabethan Club of Yale University.

“We want to celebrate the many Black, Indigenous, and POC artists … anyone who brings the plays of William Shakespeare to life with passion, precision, talent, and intelligence,” Massie said Thursday “We want to have real conversations and dig deep into questions, not only about the challenges and issues raised about these 400-year-old plays, but also, the system that surrounds Shakespeare the man, the myth, the ultimate achievement in Eurocentric high art that in many cases has been used to erase, oppress, and even harm other cultures.”

“Lastly, we want to create understanding and intentionality for Elm Shakespeare’s work in the community, looking at what we do, why we do it, and how we can do it better.”

Massie opened the night with a broad topic he dubbed “belonging.” For these five directors, it was a prickly term. Did rejection of Shakespearean norms make directors and their work any less legitimate? What did it mean to truly “belong” to the Shakespearean community as a BIPOC creative? Who belonged to it? Who was Shakespeare even for?

Ocampo-Guzman broached the topic first.

“Mi nombre es Antonio Guzman,” he began, “and I am done with Shakespeare.”

Ocampo-Guzman wasn’t always so cold toward Shakespeare. Growing up in 1980s Bogota, Columbia, the Bard had been his entire life. As an adolescent, Ocampo-Guzman found more meaning in the canon than most of his classmates. He had not excelled in sports like other boys his age. He had an affinity for poetry, debate, and theater. He was scrutinized for his talents and, before long, for his sexual orientation as well.

None of that mattered when he performed Shakespeare. The stage was transportive. Under the lights, Ocampo-Guzman could be anyone. He grew with each performance, while Shakespeare tied itself to his burgeoning self-image. Shakespeare became his career. Shakespeare became “belonging.”

“I trained as an actor in Colombia, and we did Shakespeare in Spanish,” Ocampo-Guzman said. “It was this notion that Shakespeare belongs to all of us, and, even in translation, we could relate to it and relate to the stories, just not to the language itself.”

His transition to America tested that sense of “belonging.” Colorblind casting allowed Ocampo-Guzman to play some Shakespearean roles, but his opportunities were severely limited due to his accent. His voice teacher characterized his speech as an issue that needed to be fixed. Ocampo-Guzman did not want to fix what wasn’t broken. His words were clear. He had talent. His identity was not a hindrance.

“I attempted to do these bilingual productions of Shakespeare in Florida,” Ocampo-Guzman said. “The greatest insult that I received was from the audience, saying, ‘Oh my God, that was so cute.’”

In 2006, he wrote his first academic essay. It was titled “My Own Private Shakespeare, or am I deluding myself?”

Williams identified with his struggle—she often oscillated between loving and hating Shakespeare herself. Initially, Shakespeare had been an opportunity. At the start of her career, she’d felt limited by what she called her “race, shape, and size.” Acting teacher Tommy Gomez introduced her to the canon and the opportunities it could afford her. She took to Shakespeare like a fish to water and soon turned her passion toward directing.

That was when the trouble began. As a young Black woman, Williams wanted employers to hire her for her work, not as a “gimmick” or a means to reach a diversity “quota.” She flashed a tattoo on her wrist during the panel: “Non Sans Droict,” or “Not Without Right.” The saying was inscribed on the Shakespeare Coat of Arms.

It was a statement, she explained. Shakespeare was her birthright. Shakespeare belonged to all. Williams firmly inserted herself within a white-dominated community. How much did that community truly want her?

“I spent the early part of my career really branding myself as a Shakespearean director, because I felt like, as a young Black woman, I had to prove that I could do it,” Williams said. “Nobody was just going to say, ‘oh, she’s got two master’s degrees in theater; of course, she could do it!’ That wouldn’t be the default presumption. If you are not a scholarly middle-aged white guy, you just don’t get to be the cultural authority on Shakespeare. I felt the pressures of, and wanted to belong to, the club, so I fought very hard to belong to the club. I really held on to the notion that Shakespeare is my birthright. I can reclaim anything that has been used against me.”

As racial tensions pushed to the forefront of public consciousness this year, Williams felt her need for “belonging” grow. Like Ocampo-Guzman, she took a step back from Shakespeare and reevaluated her relationship with his work. She only directed Black-authored plays this season. She said it was strange, but not unpleasant, to be a presumed authority. Williams directed texts that cared for her culturally, an experience she wasn’t used to within the Shakespearean canon. This season, she felt “belonging.”

“To Antonio’s point, do I have to keep doing this to myself? Do I have to keep showing up in a field that I’ve given my whole life and career to and still beg to belong to?” Williams said. “I show up with my master's [degrees]. I spent six seasons at OSF [Oregon Shakespeare Festival]. Still, people question my artistic choices relative to Shakespeare because they, unconscious or not, believe it doesn’t belong to me. Maybe it doesn’t. I’m not ready to concede that point. I want to still be like, ‘it’s my birthright,’ but it’s just felt better to be doing Lynn Nottage and Dominique Morisseau. I’ve felt cared for in the work. When I’m doing Shakespeare regionally, I feel left out in the cold.”

Sayet, a writer and director who currently runs the Yale Indigenous Performing Arts Program (YIPAP), noted the importance of cultural representation. Years ago, her love for Shakespeare took her to England in pursuit of a Ph.D. Sayet’s colleagues had praised her for the trip across the pond. Employment opportunities sprang up in a flurry. Still, Sayet wasn’t happy.

Something was missing, she said. She began to question her academic career, her relationship with Shakespeare, and herself. She pored over scholarship dissecting cultural, racial, and ethnic dynamics in the Shakespearean community. Coincidentally, Ocampo-Guzman’s work had struck a chord with her back then. Did she have her “own private Shakespeare?” Could she belong to a community as an Indigenous voice?

“I’ll never forget 2012,” Sayet said. “The only American representation in the World Shakespeare Festival was from The Wooster Group, and it was a group of white actors dressed up in redface. When I started casting Native people in Shakespeare productions, people would be like, ‘Oh my God, you’re so innovative,’ and I’d be like, ‘Why would I imagine a world in which I didn’t exist?’”

Sayet pivoted, abandoning her Ph.D. She began writing a solo performance piece called Where We Belong. It brought out the spirit of her Mohegan ancestors in a foreign land. It was the same land they’d traveled to 300 years prior on diplomatic missions. Using the United Kingdom as a frame, Sayet explored colonialism in her search for nativity.

“I’m constantly grappling with the ways in which we can still love Shakespeare but examine how he’s weaponized and the systems that are held within its hierarchy. Shakespeare’s language—the beautiful poetry—it is so much a part of what I really value, and, yet, I’m really trying to find ways to center all of the Native artists who are capable of that level of poetry and are just not being amplified in the same way. That’s where I’m situated currently in the spectrum of ‘belonging.’”

Cofield and Callender proposed the same answer to this question of cultural synthesis: adaptation. Fans, directors, and teachers of the Bard must stop upholding the canon as sacred. His works are flexible: they may be translated to the modern day to retain poignancy.

Both directors turned to music as examples of this standard. Cofield, who directed an Afrofuturist Twelfth Night at the Yale Repertory Theatre last year, contrasted two versions of “The Star-Spangled Banner, one by Francis Scott Key and the other by Jimi Hendrix. Even centuries apart, both renditions stirred the same feelings of hope and protest amongst war in their audiences.

“Shakespeare’s genius is that you can put Shakespeare anywhere,” he said. “You can put Shakespeare on the moon. You can find a universality in it. My objective was to really interrogate that.”

Callender turned to Beyoncé’s popular 2019 cover of “Brown Skin Girl.” He’d first heard the song as a child in the West Indies, listening to the soft hums of his grandmother. In his older years, the familiar tune had struck him like lightning. Beyoncé made the old contemporary, giving it a new meaning to millions. Callender couldn’t have been more grateful.

“That’s what I think we need to do with Shakespeare,” he said. “We have to take these amazing pieces of literature and crumple them up, really crumble them up. Then, pull them out again with all their wrinkles and with all their tears and say, ‘how can we now take this and create something beautiful?’”

“Something beautiful” meant a mode of Shakespeare accessible and welcoming to all, he added. Callender recalled growing up as a poor, Black boy hearing the racial slurs of John Simon and his contemporaries; the men deemed Black people genetically unfit for the fine arts. Callender learned Shakespeare through his love for the texts and pure spite.

Cofield read Shakespeare in a conservatory, literature firmly separate from his life in Miami. Adaptation was representation for both men. Cofield understood the text he read by coalescing vignettes from his life and Shakespearean plots. Falstaff was his “uncle in the barbershop.” Hamlet was analogous to “The Notorious B.IG.” He’d take this mentality to his future productions, like Twelfth Night.

Callender ultimately applied the same mantra as the Artistic Director of the African-American Shakespeare Company. Both men knew what adaptation meant to their diverse casts.

“I want my actors not to treat Shakespeare so precious! He’s making up words, so let’s scat! What do you sound like?” Cofield exclaimed. Callender nodded in agreement.“I remember having a conversation with an actor that I cast. I was like, ‘Loosen it up,’ and he said, ‘You mean I can be Black?’ I was like, ‘What else would I want you to be?’”

The room chuckled. Callender noted the exact reaction in some of his own cast members. He reminisced on a rendition of Romeo and Juliet he’d done with Black teens, who were the same age that the young star-crossed lovers would have been. Cast members had been their full, authentic selves, complete with rap and dance during Queen Mab’s speech. Those kids are now graduate students, some of whom are studying Shakespeare.

“It was a lyrical, musical orchestration with these young Black kids that I will never ever forget,” Callender said. “I never want kids that look like me to be terrified of Shakespeare… don’t get to the point where at 15, 16, or 17 some English teacher is droning on. That’s deadly to me! I want rhythmic! I want dancing! I want to have Caliban speak! Change the words to Caliban’s language! Make it American Indian! Make it Nigerian! Make it something right!”

“There are rhythms of our power to associate our ancestors,” Callendar continued. “When people say, ‘Wow, when I saw Feste come on that stage, that’s my uncle!’ Oh, I love that! When we have our demographics come in and say, ‘I’ve never understood Romeo and Juliet more than I understood it in this production! I’ve never understood Twelfth Night more than having seen Viola as a club singer or when Shakespeare says, ‘hold a mirror up to nature!’”

“Well, guys, this is what we look like,” he continued. “You come to my shows, and you will see what you look like. You can make your decision as an adult whether you want Shakespeare or not in your life, that’s fine! But I want you to know that it’s there! That he’s there! The language is there! The rhythms are there! Play with it! Love it! Add music to it! Change a word or two! It’s fine! He doesn’t have an agent! We’re good.”

The next installment of "Building a Brave New Theatre" will premier next Thursday, Nov 19, featuring a performance by Harlem Shakespeare Festival’s Artistic Director Debra Ann Byrd. Click here for more information.