Arts & Culture | NH Docs | Wooster Square | Film & Video

Norman Malone: “I try to encourage anyone that has a disability to just continue. You’re not necessarily playing for an audience—you’re playing for yourself. And there’s so much to learn. So much to learn.” Lucy Gellman Photos.

The first notes rang through the Church of St. Paul and St. James, hanging for a moment in the apse before they slipped out into the audience. They bloomed into a conversation, crawling into the church’s darkest, most sound-swallowing corners as the volume rose. A bat that had been circling around the nave stilled. At the piano, Norman Malone’s left hand took flight.

Malone’s performance accompanied a screening of For The Left Hand, a pick at the New Haven Documentary Film Festival (NHDocs) of which he is the main subject. Thursday night, just over a dozen attendees filled the sweltering church for the film, talkback and live concert from the musician, who has made it his life’s quest to find, play and commission music written for only the left hand after a traumatic brain injury early in his life.

He may be best known for his work on Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major, which he played with the West Hartford Symphony Orchestra in 2016 and again in 2019.

The documentary is written by Howard Reich, who worked as a music critic at the Chicago Tribune for over 40 years. Directed by Leslie Simmer and Gordon Quinn and produced by Diane Quon, it is the kind of an intimate, delightful, surprising and humane portrait of lived experience in Chicago that is Kartemquin Films’ trademark. By its end, it is also a powerful argument for normalizing an academic and artistic future for all abilities.

“I try to encourage anyone that has a disability to just continue,” he said in an interview after the event. “You’re not necessarily playing for an audience—you’re playing for yourself. And there’s so much to learn. So much to learn.”

For The Left Hand tells the story of Malone, a lifelong Chicagoan who at ten lost the use of his right hand and partial use of his right leg when his father struck him and his two brothers with a hammer to the head. At the time, he was five years into his love affair with the piano, an instrument he describes as “the force of survival” early in the film.

In a series of close ups, old family photographs, and footage of the artist in his apartment, schools, family homes and concert halls, Malone walks Reich—and by extension, the audience—through a universe and profession that was and is not built for him. When the artist left the hospital and began to recover at home, his steadfast interest in music became a sort of enigma to the able-bodied world around him. He has a straight, matter-of-fact way of telling it that reminds viewers disabled people aren't there for their pity, inspiration, or entertainment: they're too busy surviving for that.

After dozens of instructors refused to take him, Malone found Chicago-based teacher Lester Mather, who began seeking out music written for left-handed players. From elementary-level music and spirituals, the musician went on to study at DePaul University. The degree took him nine years to complete because he was also working to put himself through school, and sometimes could only squeeze in night classes.

“It got to a point where I ran out of left-hand music,” he said during the talkback.

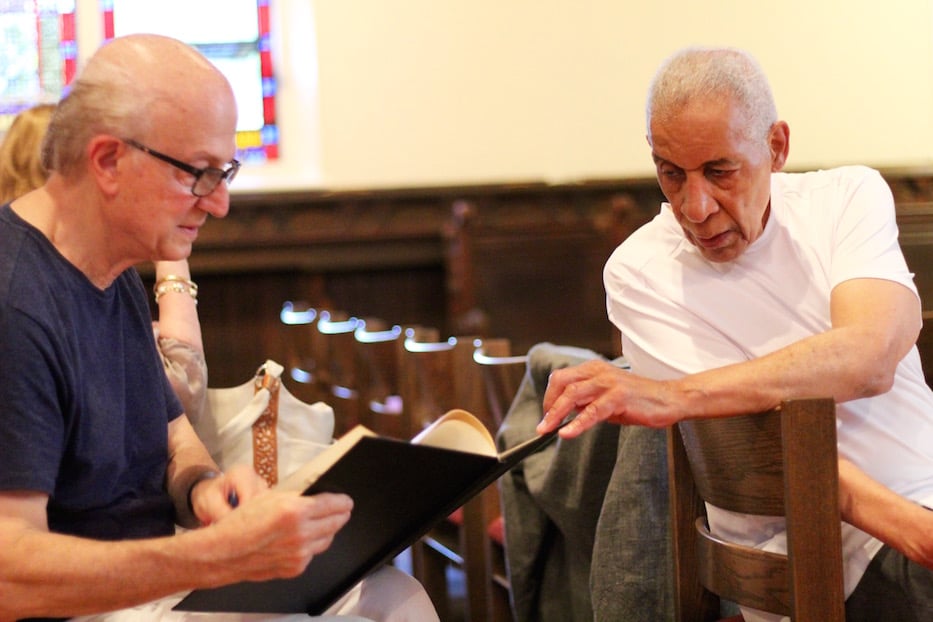

West Hartford Symphony Orchestra Conductor Richard Chiarappa and Norman Malone at the event.

His hunger for left-handed repertoire led him to Paul Wittgenstein, a concert pianist who lost his right arm during the First World War. During his lifetime, Wittgenstein was able to commission works from Sergei Prokofiev, Paul Hindemith, Maurice Ravel, Benjamin Britten and others.

The musician became the subject of Malone’s thesis, and later spurred his years of practicing Ravel’s piano concerto in secret as he became a beloved choral conductor in the Chicago Public Schools and raised a family of his own. In the film, he refers to his practice regimen as “a daily prayer.”

“They [students] never knew my story because I didn’t think it was proper,” he said in an interview after the film. “If I wasn’t teaching them, or doing a good job, that would be the issue. So they didn’t find out until after I had retired. And I thought, that’s the way it should be.”

With the Kartemquin team, Reich opens the narrative to a rich cast of characters, including Malone’s neighbors and former students at Lincoln Park High School, Malone’s son Mark, who works in music and ministry in West Hartford, Wittgenstein’s daughter Joan Ripley, Wittgenstein’s piano itself, and West Hartford Symphony Orchestra Conductor Richard Chiarappa.

Music critic Howard Reich. Reich retired from the Chicago Tribune earlier this year.

Their wide net works. While the film builds to Malone’s concert with the West Hartford Symphony Orchestra, it feels full because of the lush, people-centered and straightforward storytelling around it. With a combination of familiarity, admiration and straight up music geekery, Reich fills in context while remaining largely in the background—just as one might expect from a guy who has spent four decades telling other people’s stories.

Throughout, a viewer is aware of the systems working methodically against Malone, and the fortitude with which he pushes back against them. In one particularly stinging anecdote, he recalls being sent to a psychiatrist when he expresses a wish to study music. In another, he gets to the end of college and is told that teaching may not be tenable. His incredulity—"I’ve been training all this while, and there’s a possibility I can’t teach?!”—is palpable even through a screen.

But there are also triumphs, filmed with a careful eye. Malone has become a fixture in Chicago’s music scene, and early shots of him listening to ragtime and jazz explode with joy. His students gush about his work as part-conductor, part-dad, and it’s extremely hard not to tear up. He plays on Wittgenstein's piano, becoming a part of the pianist's afterlife.

In one of the documentary’s most moving shots, the camera is fixed on Malone, the audience at a West Hartford high school blurred in the background as he begins to play the Ravel. Then it shifts, and a viewer is watching Malone through the orchestra’s other musicians. They remember that they’re in the auditorium of a high school, where so many community orchestras rent out space. It is a love letter to the composer, to community orchestras, to the arts as a mechanism of survival and to the survival of the arts.

In both the film and the talkback, Malone and Reich advocated for a future in which the path to musicianship is clearer and more open to all who wish to tread it. A few years ago, a student came to Malone asking specifically for music written for the left hand. Malone, who keeps bound volumes with hundreds of pieces in his apartment, suggested starting on some of the same compositions he had started on many years before.

“If I can find some of these missing, lost copies of material, I would be eager to discover them,” he said. “And get some of these great pianists to start playing more of them, so that people can be exposed to it.”

In the past several years, he has also worked with composers including MacArthur Genius grantee Reginald Robinson, who wrote a left-handed piano rag for Malone in 2016. He praised pianists Leon Fleisher and John Browning, noting that their names still remain largely unknown to audiences outside of classical music. His goal, he said, is to leave a more accessible world than the one he came into.

“I hope to have contributed something by getting other composers to write,” he said. “Every time I meet a composer, I says, ‘What about writing something?’ And sometimes that’s successful, and I run into failures also. It’s quite a challenge.”

Reich pointed to the expanding legacy that Malone, as well as the film, are already leaving. When Malone originally went to the Chicago Public Schools with a proposal for playing left-handed music, they turned him down.

"They were unaware that there's over 200 years of music written for left hand alone,” he said. “If they had known that, if they hadn't been ignorant of that, he wouldn't have had to do it all himself."

The New Haven Documentary Film Festival runs through Aug. 15. For tickets and screenings, click here.