Culture & Community | Immigration | Refugees

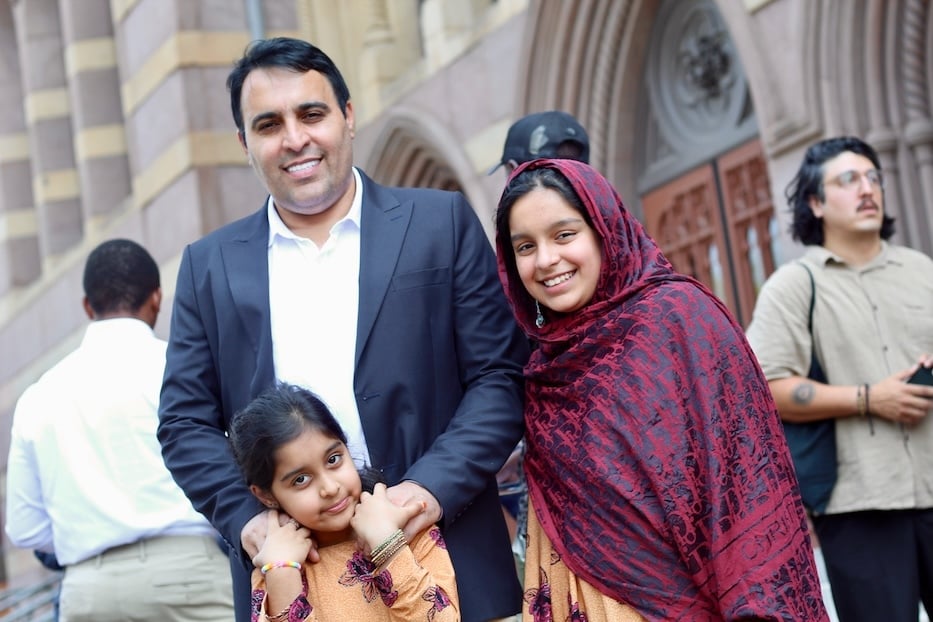

Hewad Hemat with his daughters, 6-year-old Sula and 10-year-old Rana. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When 10-year-old Rana Hemat walks into her art class, she’s usually wide-eyed and beaming, ready to take on the day. Sometimes, it’s exactly what she needs to center herself before other classes, like the science lessons she’s come to love. Sometimes, it helps her regulate her emotions, one brushstroke at a time.

Almost always, though, there’s a little tug at the back of her mind, a reminder that in her family’s native Afghanistan, she wouldn’t be able to do this. That there are so many girls like her, who just deserve to go to art class without fearing for their lives.

Rana, who is a rising sixth grader at John C. Daniels School, brought that story to Church Street Friday morning, after a press conference commemorating the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in August 2021. Organized by Elena’s Light and the New Haven Legal Assistance Association, the gathering outside of City Hall highlighted the needs of Afghan immigrants and refugees living in New Haven and across Connecticut, who now risk deportation under the Trump Administration.

Elena’s Light Founder Fershteh Ganjavi, who named the organization after her daughter.

Since 2021, close to 4,000 Afghan refugees have resettled in Connecticut, said Elena’s Light Founder and Executive Director Fershteh Ganjavi. Until January of this year, many were covered by Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and Humanitarian Parole, both of which were granted to thousands of people who fled Afghanistan under extreme duress and fear for their lives in 2021.

The problem is that neither designation provides a navigable pathway to citizenship, meaning parolees and TPS holders are vulnerable to deportation when their protected status ends. The Trump Administration announced in May that it was ending TPS for Afghan nationals, the latest in a string of anti-immigrant actions from the administration. It has also suspended TPS for people from Haiti, Venezuela, Cameroon, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

The end of such programs mean that Afghans could lose (and are losing) their visas and work permits, risking deportation at a time when their home country is still completely unsafe to return to. At the same time, the Trump Administration’s massive budget bill cuts SNAP, Medicare and Medicaid benefits for refugees (alongside millions of Americans who rely on an already-threadbare social safety net) starting next fall.

“They face a constant fear of deportation every minute,” said Ganjavi, who came to the U.S. as a refugee in 2011, after growing up outside of her native Afghanistan to parents who were also refugees. “That fear is not just paperwork. It is the fear of losing your children’s future. The fear of returning to a place where your life is in danger. The fear of going to a country where your kids cannot go to school. And the fear of being forgotten by the very country that promised safety.”

"We will fight with every tool that we have to support our Afghan community and many other immigrants that are being attacked today," Mayor Justin Elicker said.

Friday, speakers stressed how urgently Afghan refugees—including SIV holders, asylum seekers, humanitarian parolees and TPS recipients, all of whom are now at the whims and mercies of the Trump Administration—need stronger legal protections, from access to a work permit to the ability to safely remain in the U.S.

In January, shortly after taking office, President Donald Trump suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), effectively shutting the door on thousands of refugees and asylum seekers who expected to resettle in the U.S. in 2025 (Trump has since reopened the discussion around refugee admissions, but with a preference for white South Africans who were both proponents and beneficiaries of apartheid).

The administration has also begun to target Afghan Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) holders, many of whom were engineers, translators, interpreters and other contract employees for the U.S. government during a conflict that lasted for over two decades. As of last month, they include a former interpreter named Zia who Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents arrested at a routine green card appointment in Hartford.

Since last year, he and his family have been trying to build a new life in the greater New Haven area. Now, ICE is currently holding Zia at a detention facility in Plymouth, Mass., hundreds of miles away from his wife and five children.

U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal and Lauren Petersen. "It is immoral, unconscionable, and shameful for the greatest country in the history of the world to break its promises and put in prison innocent people who have helped this country, and who are here because they regard America as the beacon of hope, and opportunity, and yes, freedom and the rule of law," said Blumenthal during the press conference.

“We welcomed 90,000 Afghans into the United States, but we didn’t give a permanent immigration status to a single one of them,” said Zia's attorney, Lauren Petersen, who became emotional as U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal described the austere and inhumane conditions in the Massachusetts facility. “From day one, they have had uncertainty about their future—how to get a green card, whether they’ll be able to find a path to citizenship. And now, four years later, many still do not have a secure status.”

Petersen noted that that’s the product of years of delays, bureaucracy and red tape: the Covid-19 pandemic slowed SIV appointments, interviews and approvals, such that there were 9,260 SIV applications pending with the U.S. State Department when the U.S. Embassy in Kabul reopened in April 2021. Four months later, the city fell to the Taliban. That meant that thousands of SIV applicants were left in the lurch, and thousands more didn’t even have the chance to apply.

Even then, advocates sounded the alarm around the temporary and fragile nature of TPS and Humanitarian Parole, urging lawmakers to pass a more permanent and accessible path to permanent residency and citizenship (if passed during the Biden Administration, the 2023 Afghan Adjustment Act would have done just that). When Trump was elected last year that alarm escalated to another level entirely. It was just days into his second term that he began to sign executive orders directly aimed at immigrants and refugees.

“Paroled Afghans shouldn’t be getting deported. They shouldn’t be getting detained by ICE,” Petersen said. “They shouldn’t be. They haven’t done anything wrong. Why can’t the U.S. government get this right?”

Hemat: Everyone is afraid.

For her—and for hundreds of advocates—that means passing proposed legislation like the reintroduced Afghan Adjustment Act and Community-Based Refugee Reception Act, both shepherded by members of Connecticut’s congressional delegation. The first, initially proposed in July 2023, would create a new pathway to permanent residency for tens of thousands of Afghan nationals, who currently have no clear-cut path to applying for permanent immigration status and residency in the U.S.

The second, which U.S. Sens. Chris Murphy and Richard Blumenthal introduced this summer, seeks to push back against Trump’s freeze on USRAP admissions by resuscitating programs like the now-defunct Welcome Corps, an initiative of the Department of Homeland Security that welcomed refugees through volunteer groups that were working with formal resettlement agencies like like Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS). In the region, Branford’s Helping Families Settle is one such example.

“We will not let Afghan voices be silenced and we will not let Afghan families be left behind,” Ganjavi said.

Hashima, who can see the fear in her own family and in the wider Afghan community.

That resolve, tempered with a deep sense of fear and anxiety, resonated for speakers like Hewad Hemat and his daughters, 10-year-old Rana and 6-year-old Sula. Eleven years ago, Hemat came to New Haven after working with U.S. troops in roles that ranged from interpreter to media manager to strategic advisor. He and members of his family are now U.S. citizens (several of his children were born here in New Haven) and he serves as the president of the Afghan American Association of New Haven (AAANH).

“I have learned that many Afghan allies are now excluded from immigrating to the United States, and the Special Immigrant Visa process has slowed to a near halt,” he said, looking around as passers-by cut through the hot, humid air and listeners paid them no mind. “I urge the administration to reverse this decision. Turning our backs on these allies is not just a policy failure—it is a failure of conscience.”

As president of the AAANH and the senior manager of resettlement services IRIS, Hemat hears frequent stories that are thickly, painfully woven with the fear that refugee families are currently experiencing. He knows families that no longer leave the house without their immigration documents, and families that don’t leave the house at all. Friday, he said, many were too afraid to come out to the press conference.“Everyone is afraid,” he said.

He also pointed to the calculated gutting of Voice of America, which makes access to those stories—and to voices that are globally more likely to be silenced—harder to access.

“I feel sad, heartbroken,” he said, remembering a relative who was bound for the U.S. when he was gunned down in front of his aunt’s home. “One of the most concerning things right now is the suppression of the media and of Afghan voices. No one can get the word out.”

He also thinks about it as a husband and doting father of five. Hemat’s daughters, who are learning in the New Haven Public Schools, would not have the same access to education in Afghanistan. Since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, Afghan girls have been banned from schools starting in the sixth grade. Afghan women have been barred from universities and workplaces. That translates to 2.5 million young women and girls “deprived of their right to education,” according to the United Nations.

Arash Azizzada.

Rana, who hopes to work in refugee resettlement, is acutely aware of what that means for her peers half a world away. After explaining that “I want to be just like my dad,” providing vital services to immigrants and refugees, she spoke of her deep love for school, particularly art and science class, a wide, bright smile blooming across her face. She’s excited for the first day of school later this month, which may make her an outlier among her peers (her little sister Sula echoed that excitement).

“If men are allowed to do something, why not girls?” she mused aloud. “Girls can do the same things as men.”

Those words—and the push for legislative action—also struck a chord for Hashima, a rising senior at Oregon Episcopal School whose family came to Connecticut in 2021, amidst the chaos and panic of a city falling to the Taliban.

Apologizing for her nerves as she took the podium, she remembered a crowded and loud Kabul airport, so packed with bodies it was nearly unrecognizable. There were families afraid for their lives, babies that clung to their mothers as they cried. “Some were injured, but no one stopped to help,” she said. “Everyone was focused on one thing: survival.”

She remembered standing in a line for eight hours, until dawn streaked the sky. When her family entered a room lined with officers, they didn’t know what would come next. After checking the family’s passports, the officers placed papers in their hands. Then they waited for hours. It wasn’t until the afternoon that they were on a military plane, packed in with other families.

“Happiness was nowhere in the air,” she said, and the pain in her voice was audible. Her mother called her parents to say goodbye. “I didn’t even know what I felt in that moment. It wasn’t a joy. It wasn’t a hope. All I knew was worry. When we asked: ‘Where are we going?’ They told us, ‘Somewhere Safe.’”

That somewhere turned out to be greater New Haven, where Hashima and her siblings were able to go to school and her parents were able to settle into a community that welcomed them. She, with her siblings, became a translator for her parents, jumping between English and Dari. She worked to excel in school, learning to fit in as she reconnected with other Afghan families and other kids her age.

They became “our support system,” she said. Still, she grieves the life she left behind, and the knowledge that she can’t safely return to her home.

“It has been four years since we arrived in America, and I still miss home,” she said. “The school mornings, full of laughter. Friday night sleepovers at my grandfather’s house with my cousins, playing hide and seek. I miss walking through my neighborhood, feeling like I know everyone, like I belong. I miss my childhood.”

“My parents made sacrifices so my brother and I could study,” she said. “They stayed strong even after losing everything. They protected us. From them, I learned that life is a fight, but one you can win if you choose not to give up.”

Now, she said, she and the members of her family are terrified to have that all ripped away. Everywhere she and members of her family go, they bring their immigration documents with them. It scares her that ICE, which she once thought of as within the law, is acting with impunity, showing up at routine court appointments and smashing in car windows. She’s scared of losing her access to education, when she’s right on the cusp of college.

“One of the most important things is my education and my safety,” she said. “If I go back, I won’t be able to go to school.”

Arash Azizzada, co-founder and executive director for Afghans for a Better Tomorrow, kept it simple as he brought the conference to a close .

"Americans can do right by us," he said. "Afghans deserve dignity, not bans. Not deportation."