Arts & Culture | History | Grove Street Cemetery

| Ashleigh Huckabey Photo. The image below of Sylvia Ardyn Boone is credit Wikimedia Commons. |

New Haveners may have heard of Eli Whitney, the Yale Graduate and American philosopher known for his invention of the cotton gin.

They may know the story of Noah Webster, the American lexicographer who invented the first American dictionary and spelling and grammar textbooks. Or Walter C. Camp, a former owner of the New Haven Clock Factory and the “father of American football.”

But what about Mary Goodman, Sylvia Ardyn Boone, or Beatrix Farrand? Does Laurel F. Vlock ring a bell? What about their stories?

Those questions landed at the New Haven Museum last Thursday evening, during “Remembering New Haven Women: Four Centuries of Women’s History” from Friends of the Grove Street Cemetery. The event included a talk from Judith Schiff, a lifelong New Havener who is now chief research archivist in manuscripts and archives at the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University, as well as filmmaker Karyl Evans and director and multimedia producer Vera Wells.

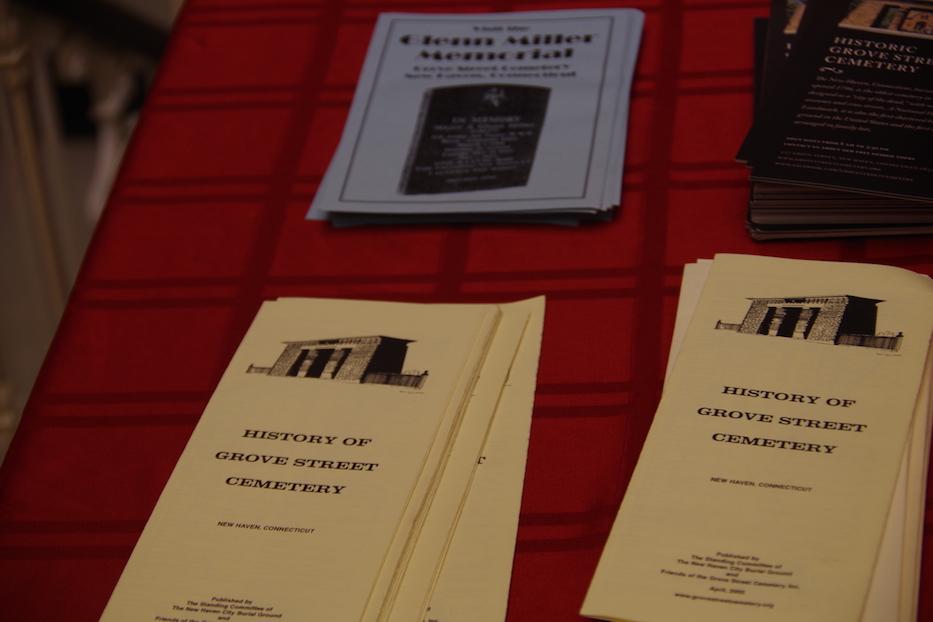

Some of those stories, Schiff explained, lie with the centuries-old bones in the Grove Street Cemetery. In 1796, the cemetery opened as New Haven Burying Ground, making it the first planned cemetery in the country. Since, it has become known as the final resting place for some of Yale’s most elite and infamous graduates, 12 Yale presidents, prominent professors, family members, and other members of the university. It has been designed as a “city of the dead,” with avenues and cross streets that bear names.

Today, visitors can enter the Egyptian-inspired gates of the historical grounds, where they have a chance to travel back in time. Beyond an entrance that reads “The Dead Shall Be Raised”—a reference to Corinthians—they can read headstones inscription by inscription. Well-trodden paths criss criss the ground, with flowers neatly arranged at some of the graves.

But among the memorials to many of the city’s ostensibly great men, where are its great women? Do they even enter one’s imagination?

According to Thursday’s presenters, not often enough. Each came with PowerPoint presentations, several slides and photographs accompanied by historical facts the invited the crowd to imagine what the lives were like of each woman honored.

What seemed like centuries of history was distilled into five-minute segments. Each presentation took on vivid dimensions, describing in detail a handful powerful women in New Haven and why they were relevant to the development of the city and the university.

“Women have historically been underrepresented over time,” said Evans, the documentary filmmaker behind The Life and Gardens of BEATRIX FARRAND among other works. “History is changing, men have been at the forefront of history, it is our time now.”

Evans explained that Farrand, who was author Edith Wharton’s niece, fought through the challenges of working in a male-dominated profession to successfully design over 200 landscapes during her 50-year career. Before she died in 1959, Evans estimated that she “designed over 75 percent of Yale’s campus, and many of us do not know that information.”

During Farrand’s lifetime, Evans found that landscaping and architecture at Yale was seen as male domain—despite the fact that women were often responsible for the ideas and sometimes for their implementation.

“I want to be a voice for women who would not have had voice,” Evans said, “those names mentioned on historical sites and famous buildings are not women, we must continue to do this work to stand by their stories and fight.”

Speaking later in the evening, Wells said that she has dedicated her entire life to teaching and honoring the legacy of Sylvia Ardyn Boone (pictured above), a professor of art history and African art who became the first tenured Black woman at Yale in 1988, just five years before her death. Over two decades after her death, Wells is the literary executor of Boone’s estate and the founder of the Sylvia Ardyn Boone Memorial Project.

She said she has made it her goal to honor Boone’s ideas and ideals of what Black beauty looked like, and how it translates to people everywhere. Boone’s teachings focused on African art, female imagery, women's arts and masks.

“Yale went co-ed in 1969, I graduated from Yale, class of 1971 as a member of the first undergraduate class to include women,” Wells explained. At this time, there were no Black women professors or women of color in the departments at Yale.

Wells, who travels to different institutions across the country to teach about the historian, explained that she was one of the first coeds who originally proposed the Yale seminar on Black Women, which then recruited Boone to teach it in 1970—beginning their journey of co-organizing the Chubb Conference on the Black Woman.

“Sylvia never discussed her age, she was my mentee but then also became my close friend,” Wells recalled. “… At the time of her death, Yale had three different birthdates for her, since she was born into slavery, there were not many accurate records kept on Black people.”

Boone, born in Mount Vernon, New York, was the fifth and youngest child in her family, with four older brothers. She lived a very lonely childhood, Wells said: her mother died when Boone was just an infant, leaving her no choice but to develop into an independent and hardworking woman.

She was a smart student, Wells recalled. As a teenager, Boone was honored as a Regent Scholar, and then left home at 16 years old to receive her Bachelor of Arts Degree from Brooklyn College. She then went on to get a Master’s degree from Columbia.

“Prior to teaching at Yale, Sylvia was friends with many historical Black writers and philosopher,” Wells said. ”Maya Angelou was her roommate. W.E.B. Dubois was a friend and colleague.”

As a world lecturer and traveler, Boone made her first international trip with Operation Crossroads Africa, a group led by the Rev. Dr. William Sloane Coffin, who at the time was the chaplain at Yale. For a period of time, she also studied at the University of Ghana. In 1970, she came to the university as a lecturer in art history.

That's when she met Vincent Scully, then the chair of the department. According to Wells, the two had several discussions that would change the course of the university's history. In 1979, she came on to the art history faculty fill time. Nine years later, she became the first Black woman to get tenure at the university.

“She was pivotal in the creation of the Amistad Memorial that now stands in front of the New Haven City Hall,” Wells said. In addition to art, Boone also wrote the first authentic travel book about Africa, titled West African Travels: A Guide to People and Places.

Boone passed away in 1993 at age 52. Her funeral was held at Yale’s Battell Chapel, and she was buried in the Grove Street Cemetery. Currently at Yale, there is the Sylvia Arden Boone Scholarship and Prize, awarded to the best written work by a graduate student on African or African-American Art. Wells established the Fund in 1971, and the fund is still being presented today.

“I push for Sylvia because I don’t want her to die,” said Wells. “I went through everything to ensure that the world knows who she was, and still is today.”

Visitors can view Boone’s resting place in addition to the many powerful women honored, at the Grove Street Cemetery. Visitors are able to receive guided tours by Darlene Casella, on selected Saturdays throughout the month.