Best Video Film & Cultural Center | Hamden | Arts & Culture | Film & Video | COVID-19

| Organizers Emalie Mayo and Sha McAllister (at right, seated) with Elm City Lit Fest Founder IfeMichelle Gardin. Thursday was also Gardin's birthday. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

On screen, Jackie Robinson was up at bat. He coated his hands in dust and took a few practice swings. From the stands, his wife Rachel held her breath, so nervous she could barely watch. Under a night sky in Hamden, two dozen people sat transfixed, glued to a story that was over 75 years old.

The ball whirred through the air and made contact with the bat. Both the baseball and Robinson became airborne.

Thursday, the Hamden Black Film Mini Series brought Robinson to the screen with 42, the Jackie Robinson biopic starring Chadwick Boseman. The film tells the story of Robinson, the Black baseball player who broke the color line when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. A few dozen attended the event, held on the sprawling lawn of Spring Glen Church.

The series is a collaboration among “Ignite The Light” Founder Shamain (Sha) McAllister, Best Video Film and Cultural Center, the Hamden Department of Arts and Culture and Spring Glen Church Pastor Jack Davidson. Emalie Mayo, who has joined the group in an advising role, is a co-coordinator of the Elm City Lit Fest.

To stem the spread of COVID-19, the three-part series is held outdoors, with mandatory mask wearing and social distancing. The town of Hamden is also doing contact tracing.

| Sasha, Elois and Aria McCollum with Angelina and Rachael Skojec. |

As night began to fall, attendees rolled in, propping up lawn chairs and unpacking snacks, bug repellent, and face masks. Some came equipped with blankets and quilts for the damp, dropping temperatures. Close to the church, organizers did last-minute tests on a screen and nest of equipment. Someone brought out a rack of extra folding chairs from the church. Every 20 minutes, the 228 bus trundled by, going from half-full to totally empty in its final hours of the day.

As one of the first to arrive, Hamdenite Rashanda McCollum found a grassy patch just to the right of the screen, laying out a blanket as her daughter Aria checked out the Moon Rocks Cookies truck with two of her friends. Beside her sat her mom Elois and three-year-old dog Sasha, whose purple stroller doubled as the best seat in the house.

McCollum, who works as the executive director of Students for Educational Justice, said she was excited to see the film but expected it to feel bittersweet. Boseman passed away last month at 43 years old, after a four-year battle with colon cancer. Before his death, he was known for the empathy and grace with which he imbued his characters, Black men from Robinson to Thurgood Marshall to T’Challa, the now-heralded Black Panther of Marvel’s Black Panther universe.

“For me, it was important to come out,” she said. “The film itself, I haven’t seen it. I loved that it was being shown in a community format. It has both entertainment value and feels timely.”

13-year-old twins Angelina and Rachael Skojec, who had joined McCollum, said they were looking forward to the film after days of distance learning and a COVID-19 scare at one of the local schools. Before the pandemic, they went to the movies as a bonding activity with their dad. Now, the pandemic has turned their year upside down. They don't go out anymore. They've lost family members in the midst of the pandemic. An outdoor movie night felt stunningly normal.

“I don’t get to watch movies that often anymore,” said Rachael. “Stuff like this is really rare for me.”

| Ann Ruhlman. |

In the front “row”—a neat line of orange traffic cones—Ann Ruhlman also settled in. A Spring Glen resident and lifelong cinephile, she walked the few blocks from her home after reading about the series in the newspaper. For months, she has felt at sea without a COVID-safe movie theater to go to.

Her favorite summer activity, the New Haven Documentary Film Festival, didn’t work for her in its largely-online format this year. Movies streamed at home aren’t the same, she said. The outdoor format gave her a reason to get back out into the community while doing one of her favorite things.

“I’ve missed it for a long time now,” she said. “Since the pandemic started, I haven’t really been to anything. I love the movies because it’s like going to another world.”

Dusk rolled in. Across the street, a band in front of Best Video was winding down its set, strains of folk and bluegrass floating in the twilight. A few just-on-time attendees swung into the parking lot, jogging across the lawn to set up chairs. William Foster, a professor emeritus at Naugatuck Community College, got up to introduce the film.

Foster urged the audience to remember two numbers: 42 and 47. Forty-seven was the year that Robinson, in the face of racist threats that dogged him for the remainder of his career, broke the color line in Major League Baseball. Forty-two was the number on the back of Robinson’s jersey, officially retired from the sport in 1997.

| "He's an icon, but Jackie Robinson was more than that," Foster said. |

“He’s an icon, but Jackie Robinson was more than that,” he said. “You’ll see how his reserve was tested. People liked him or they didn’t like him. But he won them over because he was good at what he did.”

As the opening credits rolled, the crowd fell to a hush. Light danced off the screen. The film opened on a grainy, compressed history lesson that jumped from segregationist policies to Branch Rickey, who served as the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1943 to 1950. As a camera swept across his office, Rickey puffed on a cigar and announced that he planned to invite a Black player onto the team.

“I don’t know who he is or where he is, but he’s coming,” he declared.

Audience members seemed to lean in a little closer; a few munched on bags of popcorn they had brought from home. The scene shifted to Robinson somewhere in the South with the Kansas City Monarchs, a powerhouse team in the Negro National League. The plot had started barreling forward, like a pitch in perfect motion.

Across the lawn, people started interacting with the film. Someone snapped as Robinson made his ascent from the Monarchs to the Montreal Royals to the Brooklyn Dodgers in a matter of two years. When manager Burt Shotton looked around the locker room and took a moment to identify Robinson—the only Black player on the team—a cackle went up from the crowd.

Pint-sized viewers watched as Robinson inspired kids who came to watch him play, just as Boseman himself later redefined who and what a superhero could look like. A few adults smiled through their masks as the film traced the great love story between Robinson and his wife Rachel, who went on to be a professor of nursing at Yale and is still alive today. Masks stayed on; eyes crinkled at the edges. Very few weren’t misty by the end.

As it played in Spring Glen—a historically redlined and still predominantly white neighborhood—42 felt timely, like the beginning of a conversation the town still needs to have. In the film, Robinson’s teammates use language soaked in white supremacy that isn't as antiquated or disorienting as it perhaps should be. In the 77 years since he broke the color line in baseball, racism has lived on in not only Major League sports, but in the de facto segregation of public schools, neighborhoods, and access to basic resources.

Robinson's own history intersects with segregationist policies in New York and Connecticut: he and his family were kept out of housing developments in Purchase, Port Chester, Greenwich and Stamford through the process of redlining. They ultimately settled on Stamford, where Robinson lived until his death in 1973.

Almost everyone in attendance had a Jackie Robinson anecdote, from young, squeaky-voiced moviegoers to those who were fully grown. Hank Hoffman, who runs Best Video and came wearing a New York Mets patterned mask, has a baseball signed by Robinson. Former mayoral hopeful Jay Kaye said that Robinson had visited Spring Glen in the early 1970s, during the time that Rachel was at the Yale School of Nursing, to have dinner at a colleague's home. That colleague's kid is now Kaye’s very grown up friend.

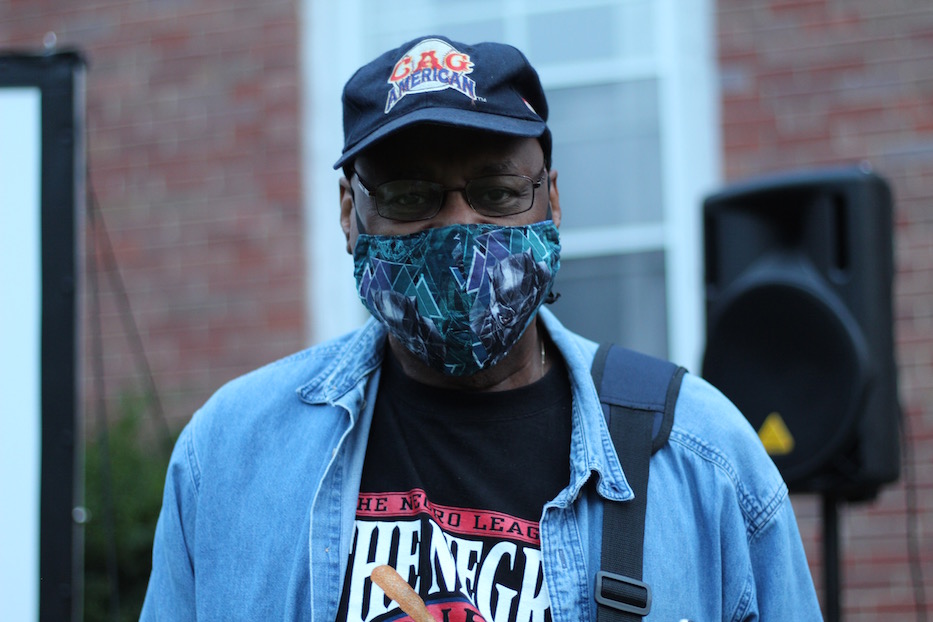

| M-Pire Auto Club Members Davon Darden, Wayne Williams, Kendall Threatt, and Lawrence Jones. Jones said they came out to the film for the opportunity to be in community after months away from friends in New Haven and Hamden. |

During a short talkback, Foster suggested that the story of Robinson can give an audience hope. He pointed to moments in the film where Robinson’s teammates pushed through some of their own racist beliefs—like a petition to get Robinson off the team—to defend him as they learned about the danger and ugliness of American racism. He urged attendees to take that message to heart in their own lives, lived in a progressively divisive country.

“You see him as a human being fighting for himself, ” Foster said. “And then some people come and support him."

“Despite what we watch, what we hear, what we see on our cell phones and TV,” he added, “There is common ground.”

The Hamden Black Film Mini-Series will return with a screening of Brown Sugar on Sept. 25 and Do The Right Thing on Oct. 3. Both screenings begin at 7:30 p.m. at Spring Glen Church. Find out more about the series on Facebook or in this article about its genesis.